Policy Solutions to Address Economic Inactivity Among Over 50s

Graeme Roy and Muiris MacCarthaigh

At the International Public Policy Observatory, we seek to learn from domestic and international experiences – including what works and what has not worked – to help inform local decision-making. To examine the policy solutions needed to address these issues, IPPO in partnership with the Economics Observatory will host two roundtables in September and October 2023 with a focus on the Northern Irish and Scottish experiences of inactivity and related policy interventions. On the 13th September, IPPO will host a roundtable on the nature and extent of the inactivity problem for over 50s. On the 10th October, a second roundtable will look at the issue of inactivity due to reported ill health.

Unemployment has reached historic lows in many parts of the UK. However, the economic inactivity rate, which had generally been falling in recent decades, increased during the pandemic. According to Jonathan Wadsworth and Stephen Machin writing for the Economics Observatory, there are around 350,000 more people classified as economically inactive compared with the pre-pandemic period.

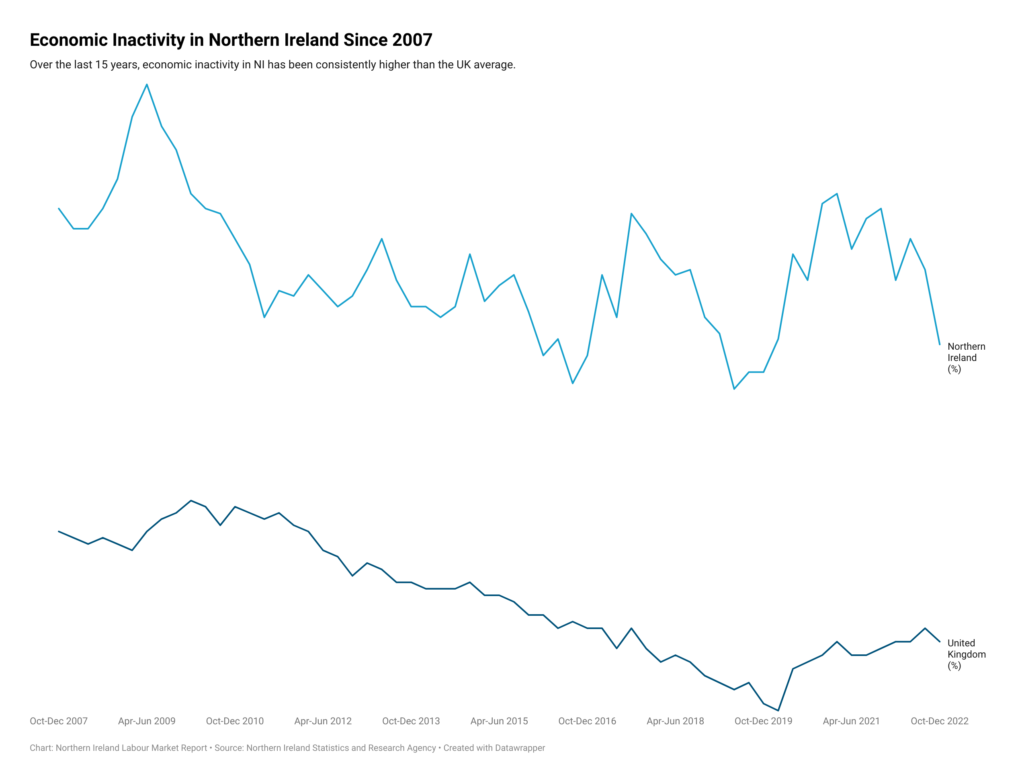

Within these headline figures, there remains significant variation by region. Rates of economic inactivity are as low as 18% amongst those aged 16-64 in the East of England and as high as 26% in Northern Ireland (where sickness and disability rates have traditionally been high). Within regions, there are significant variations too. In North Lanarkshire, for example, economic inactivity rates are nearly 30%. In Inverclyde, over one in two of those who are inactive report the reason as being ‘long-term sick’. This compares with a GB equivalent figure of just one in four. The Covid-19 pandemic reversed some progress that had been made in reducing inactivity, with considerable regional variation also.

However across the UK, much of the reason for this economic inactivity increase has been attributed to a rise in those reporting as ‘long-term sick’ (ONS, 2023). The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimate that the number of new disability benefit claimants doubled between 2021 and 2022. The increase in inactivity is being driven by two age-groups. Those aged 50+ and in the 16-24 group.

Concerns about this rise in economic inactivity have prompted new debates about the right policies aimed at either discouraging early retirement, encouraging the labour force participation of parents with young children, and tackling the long-term causes of ill-health and disability (including mental health).

But the policy solution is likely to be complex. Government efforts to boost activity among the newly inactive may not reach all of those affected. The problem traverses issues of gender, geography and even administrative burdens, involving different agencies and levels of government. Also, many newly ‘inactive’ have come from high-paying, professional jobs and who are living comfortably in early retirement, and no policy is likely to prompt them to ‘un-retire’.

The regional variation in the structural causes of inactivity, demographics and policy levers means that a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution is not going to work. A detailed understanding of local challenges and opportunities is needed. In Northern Ireland for example, the nature and causes of inactivity differ from other parts of the UK. In particular the rate of economic inactivity has remained consistently higher than other working age populations. At a rate of 26.3%, this is some progress towards achieving a target of 23% by 2030 as set out in the Belfast Economic Inactivity Strategic Framework. Previous consultations from the Belfast City Council identified the following groups as high contributors to inactivity; older people, the long-term sick, people with disabilities and lone parents.

Older people of working age were also one of the most affected groups during the pandemic. Employees aged 50 years and over reported working fewer hours than usual (including none) from Dec 2020 to February 2021 than those aged under 50 years. Many were also affected by covid-related redundancies. Over a quarter of furloughed employment were people aged 50 years and over (1.3 million), with 3 in 10 of older workers who believed there was a 50% chance or higher that their contract will be terminated following the end of the scheme.

The likelihood of re-employment following redundancy is significantly lower for older people than it is for those aged 16-24. Other significant contributors to economic inactivity reflect difficulties in the management of chronic illness and work-limiting disability. Rates of employment and economic inactivity are also affected by the severity and counts of health conditions. Reduced mobility, muscle fatigue and chronic pain impair some individuals’ abilities to perform the required daily activities/specific job requirements.

In Northern Ireland, over one fifth of the population aged between 16-64 are disabled. At almost a quarter of a million people, this represents a significant proportion of the NI labour supply. Northern Ireland also has the lowest employment rate for people with disabilities within the UK and the largest UK disability employment gap. Research from the UUEPC found that three-fifths (59%) of people with disabilities report their conditions severely limited their daily activity in 2022. The employment rate for disabled persons with one health condition is 48% compared to only 15% for those with four or more chronic health conditions.

Disparity in the employment outcomes for people with disabilities and those without point to evidence which reflects the additional barriers and constraints experienced when trying to access and stay within the labour market. Differences in occupation, qualifications, working hours and transportation access contribute to rising poverty levels within this group and variance in household income.