The Importance of Coordination Across City, Regional and National Policymakers in Delivering Net Zero

Graeme Roy

Cities – and their leaders – are crucial actors in efforts to tackle climate change. In 2020, cities comprised 67% of global emissions (IPCC, 2022). It is perhaps not surprising therefore, that city leaders have joined their national and international counterparts in setting ambitious targets for emissions reductions.

In the UK, the Government has set a target to be net zero by 2050 (in Scotland, the target is 2045). Cities across the UK have declared an ambition to go faster. Manchester has set a target to be net zero by 2038; Liverpool and Birmingham 2030. Nottingham aims to become the first carbon neutral city in the UK and to do so by 2028 – just five years from now.

Achieving these targets will require innovative and bold policy interventions across all aspects of policymaking, from transport through to how we heat and power our homes.

But it will also require innovative approaches to delivery, particularly in coordinated policy interventions across tiers of government and between public and non-public sector bodies. Failure to appreciate the importance of implementation (and its challenges), will mean that policy actions to deliver net zero will likely come unstuck and become mired in political disagreement and rancour.

Net Zero and Glasgow

Glasgow is an interesting case study. It’s a city that can trace its rapid and considerable growth back to how, early in the industrial revolution, its rich local deposits of coal and iron-ore helped to fuel growth and trade. But it’s also a city that has faced the costs of de-industrialisation and long-term effects on public health from industrial pollution and inadequate housing.

In 2019, Glasgow set a target to be net zero by 2030. But in doing so, it has sought to link its efforts on the environment to wider ambitions to help support the economic regeneration of the city through a ‘Just Transition’ and “Glasgow Green Deal”. All efforts and actions of city policymakers are to be aligned upon the following goal:

“The step change in action required by the climate crisis must also address the existing vulnerability and fragility of people and our economy exposed by COVID-19 – addressing emissions and climate risk alongside poverty and inequality, creating high quality green jobs and opportunity in a redefined notion of what prosperity looks like in the 21st Century.” (Glasgow City Council, 2021).

In recent work, researchers at the Universities of Glasgow and Strathclyde mapped the intergovernmental links and implementation challenges in delivering net zero in Glasgow.

We highlight two issues related to the policy problem – namely the measurement of emissions and the policy tools in urban areas – before stressing the importance of issues of agency, boundaries and intertemporal impacts.

Whose Emissions?

There are ongoing debates about how to measure global greenhouse gas emissions (such as via inventory or atmospheric measurements) and who (and where) they should be accounted. In a local and city context, these issues become even more pertinent.

Emissions data for Glasgow and all other UK cities – including those used as city targets – are provided from official BEIS statistics developed by the UK Government. Alternatives are possible such as the internationally widely used GHG Protocol for Cities (GHG Protocol, 2021). Consumption-Based Carbon Footprints provide another alternative and show the total global emissions related to consumption within a specific geography through the local, national and international supply chains. Whilst broadly seeking to capture the same thing, different measures can yield substantially different outcomes.

The choice of metrics for city level emissions might seem a technical issue. But it raises important questions about whether a city is on target or not, and the ‘exporting’ and ‘importing’ of emissions together with the appraisal of policies.

Does the emissions from a commuter who lives in a neighbouring district, but who drives through the city to reach another location, ‘count’ towards Glasgow emissions? Or a business based in Glasgow producing goods for export?

There are also important questions about what ‘scores’ as a city’s emission and what doesn’t. Emissions from air travel (international or domestic) – such as Glasgow Airport – or shipping are not included in city emission baselines or typically their targets. However, they are included in national inventories.

Whose Policy Responsibilities?

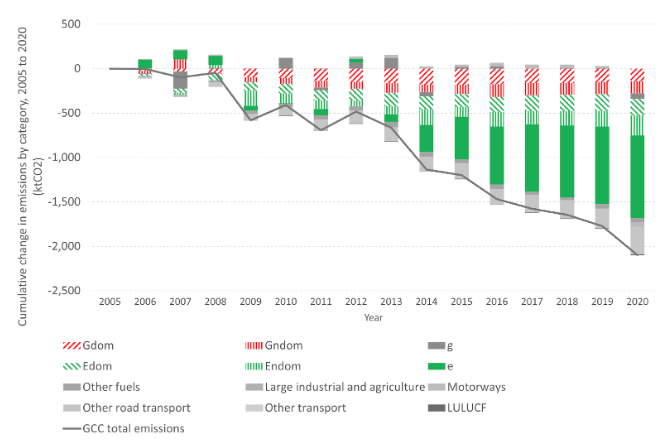

The recent performance of emissions for Glasgow suggests that between 2005 and 2019 emissions for Glasgow fell from 4,108 ktCO2 to 2,414 ktCO2, a fall of 41% (Source: BEIS). But as the chart shows, much of this fall has been driven by a small number of sectors and activities.

Cumulative change in emissions, Glasgow City: 2005 to 2020*

Interestingly, few of these changes have originated from within city policymakers’ competencies. As the chart shows, most of the decline in emissions has been from national (and to a lesser extent regional – i.e., Scottish) policies to decarbonise the electricity system.

In looking at future areas, the ability of the city to dictate the pace and scale of any transition to net zero will be similarly shaped (and constrained) by the balance of policy autonomy and political power vis-à-vis national and regional policymakers.

Take transport for example. For Glasgow, transport emissions now comprise 32.6% of all city emissions, and have increased in absolute terms since 2005. But trunk roads – which carry nearly half of road traffic in the city – are the responsibility of the Scottish Government; fuel tax and road tax are the responsibilities of the UK Government; with the city responsible for local roads, including congesting charging and workplace parking levies. A similar mix of complex responsibilities exists in public transport, where the local rail network is overseen by the nationalised Scottish Government-owned ScotRail, but the regulation of buses is the responsibility of the city council.

So How to Navigate Through This?

- Identification of agency

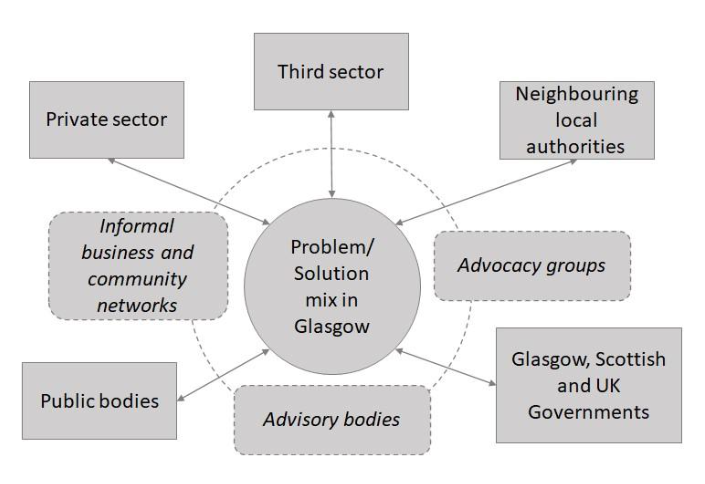

Solutions to ‘wicked’ problems require multiple agents to be involved. Often these agents exist across distinct institutional settings: policymakers, businesses, households, third sector organisations, etc.

But securing a reduction in carbon emissions, whilst ensuring a just transition and economic revitalisation for the city, involves a complex web of agents not just across different institutions and networks (arguably on an unprecedented scale) but also within them.

What is crucial is identifying where agency to make change, or influence change (including from other actors), rests. A useful exercise is to map out the key stakeholders each with a role in supporting a transition to net zero. For cities like Glasgow, this will include private sector and community networks, such as Sustainable Glasgow – a network of leading employers supporting action on climate change – different tiers of government (national, regional and municipal), neighbouring local (or municipal) authorities, the private and third sector and public agencies.

Stakeholder groups contributing to solution identification

- Identification of boundaries

A second issue is that of boundaries (or externalities). The breadth of the net zero challenge means that spill-over effects will be complex.

This has the potential to lead to conflict between the boundaries of policy objectives. For example, a rise in transport costs – perhaps through a flat-rate workplace parking levy – might lead to a rise in inequality. Issues of boundaries may also arise most obviously in respect of geographical locations. Nearby localities to Glasgow, such as East Dunbartonshire and East Renfrewshire, have large portions of their working age residents commuting to the city for work.

Whilst it might be tempting to boldly announce a city’s ambition to achieve net zero, the reality is that it cannot be achieved without a detailed plan of collaboration and coordination between different policy areas and localities.

In the Glasgow context, the Glasgow Green Deal being developed is a positive step to convene a discussion with different partners, and mindful of the different instruments to be co-ordinated, to get to net zero.

- Identification of time periods and choreography

The third issue is the intertemporal nature of the policy choices and strategies to achieve net zero. Setting out such an ambition is one thing; delivery is another.

Uncertainty exists over what technologies, changes in behaviour and investments will be most impactful. Changes in the form of solutions will also take time to appraise, design, implement (particularly if legislation or behaviour change is involved) and evaluate. Investments in this field, do not typically allow for incremental learning as many decisions taken lock-in (or lock-out) future pathways. Contestation will also likely emerge not least in terms of the choreography of decision-making.

Again, transport provides a useful example of the practical challenges involved.

Any decision over disincentivising private (petrol/diesel) car use, for example, requires alignment with public transport provision. But this will also require a change in attitudes – Glasgow residents still identify road maintenance as more of a priority than public transport.

Financial coordination across tiers of government – including perhaps changes to accounting structures too – will also be needed. The 2019 recommendation from Glasgow’s Connectivity Commission for a new light rail system is estimated to cost “somewhere between £11 billion and £16 billion” with a “timescale of 25 to 35 years to completion” – three times longer than the time remaining on the city’s net zero target.

- Where next?

Much of the debate on net zero has – quite rightly – focussed upon the policy levers with the potential to accelerate emissions reduction. But these levers are uncertain, create spill-overs and are controlled by different tiers of government.

The upshot is that there are thorny challenges requiring the convening of a wide set of actors and the managing of parallel objectives that shape practical policy action.

The experience of cities like Glasgow suggests a positive convening role for local policymakers closely connected to the intervention context. But designing robust frameworks for managing and coordinating efforts on the ‘shared mission’ is an important aspect of the policy agenda that requires just as much policy thinking as individual policies on net zero itself. One practical opportunity therefore is to ensure that any debates over future city deals, or devolution for cities, embed net zero policy and policy coordination at their core.

*The DBEIS data publishes emissions for each local authority (LA) in the UK by a number of categories, relating to transport, land use changes, and fuel use, including electricity and gas consumption. We can separate the cumulative change in emissions by each category over time, and – with additional data for each LA on (domestic and non-domestic) electricity and gas consumption – further split emissions from these categories into the change in emissions that is explained by the changes in the consumption of electricity and gas (“Edom” and “Endom”, and “Gdom” and “Gndom”, respectively) and the change in emissions explained by changes in emissions intensity of each (ktCO2 per GWH), “e” and “g” respectively.