What have we learned about online learning? UK and global evidence on the emergency remote education of schoolchildren during COVID-19

The pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on education. With the UK having recently marked 12 months since the beginning of the first lockdown, it is timely and crucial to reflect on what has been learned about online and blended modes of learning, and to identify positive areas of change for practice and policy going forward

Authors: Dr Melissa Bond and Faye Bolan

Executive summary

- Global impact. The COVID-19 pandemic has heavily impacted the K-12 (Kindergarten to 12th Grade – i.e., the years of state-funded education) education sector worldwide, with most schools and learners having to adapt to blended or fully remote (online) learning with limited preparation, resources and training.

- Online learning switch. Global responses to the crisis varied but included increased use of video conferencing tools, online learning platforms and paper-based packages to support home learning. Technology applications and platforms that promote peer interaction and collaboration were shown to increase student engagement.

- Digital divide. Increased reliance on digital technologies has highlighted systemic issues around access to devices and the internet and digital competencies. A study of families in England found that only around half of primary school students had access to a computer for learning, with 10% using a mobile phone or having no access to a device at all. In Scotland, 48.2% of primary school pupils had to share a device with someone else. Digital skills gaps were also identified in students, teachers and parents/carers.

- Learning impact. While screen time increased for primary school children during lockdown, their total learning time decreased from 6.3 hours to 4.1 hours per day, with a bigger drop seen for secondary school students, from 6.59 to 4.15 hours, according to a large-scale survey in England.

- Role of caregivers. Parents and carers played a crucial role in children’s education during school closures, both in supporting children with the use of new technologies and in helping to engage and motivate young learners. While the added burden may have negatively impacted parent and carer mental health and wellbeing, one survey revealed around a quarter of parents reported that their relationship with their children had improved, and another survey found that 53% of parents felt more engaged with their child’s learning than before lockdown.

- Vulnerable groups. Limited evidence is available on how the pandemic has affected certain vulnerable populations, such as students with special education needs and disabilities (SEND) and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds. However, parents of students with SEND reported that their children were more likely to struggle with understanding tasks and sticking to a routine while learning at home.

- Current picture (global). According to the COVID-19 Global Education Recovery Tracker, at least 51 countries have completely returned to in-person education, particularly within sub-Saharan Africa and the East Asian-Pacific region, but there are still more than 90 countries fully closed, or with students being taught via a range of hybrid learning modalities.

- Current picture (UK). The UK authorities in Scotland, England, Northern Ireland and Wales issued guidance stating that schools should continue to provide a hybrid learning model, to allow continuity of learning between students learning in-person and anyone self-isolating.

- Implications. The remote learning switch during COVID-19 could have far-reaching implications for education policy in the future. Despite the numerous challenges identified, there are also opportunities to create a more flexible, inclusive and equitable education system.

- Further research is needed within the UK to:

- Examine methods for online assessment, in light of the disruption and devastation caused by the cancellation of GCSE and A-Level exams throughout the UK in 2020.

- Provide evidence on how schools in the UK used technology differently during the second and third lockdowns, and why.

- Focus on the experiences and views of students – and particularly those from vulnerable populations, e.g. migrants and refugees, SEND – as well as teachers, school leaders and families.

How has K-12 education been impacted as a result of COVID-19?

Globally

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on education around the world, affecting at least 1.7 billion students and 63 million teachers, with most education systems not having anticipated or been prepared for the ramifications, and an average loss of 47 days of in-person instruction. Systemic issues of equity, access, and quality quickly became more pronounced, alongside issues of student digital competencies for learning, and teacher technological pedagogical knowledge and skills. Confusion over government guidance was a particular problem, and even if guidelines on how to introduce remote learning were published, they were not widely known about.

Many countries provided some form of additional support to boost access to online learning, including providing subsidised or free internet access (e.g. Indonesia), providing students with laptops or mobile devices (e.g. Canada), and providing free access to software (e.g. Denmark). Educational systems that already had structures in place were able to act more swiftly, although 60% of the countries surveyed by the UNESCO, UNICEF and World Bank reported creating new learning platforms. Despite the time and effort put into developing a range of new resources to support learning, seriously impacting teacher wellbeing and workload, many school leaders, teachers and parents have reported lower levels of student engagement and wellbeing for some students.

The increased use of technology during the pandemic, particularly when using personal devices and home Wi-Fi networks, has increased cyber-security concerns across education sectors. In schools, safeguarding has also been a key consideration when making decisions about which platform to and digital tools to use for remote learning.

Within the UK

In the UK all schools were closed by 20th March 2020 due to the pandemic, except for vulnerable children and those of essential workers who were allowed to continue attending in person, but with social distancing in place. School governance in the UK is incredibly complex, with schools needing to navigate educational policy at national UK, devolved country (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) and regional levels (local authorities), as well as taking into account other local support structures and organisations. This led to an overwhelming amount of information for schools to process and respond to, with advice sometimes changing several times a day leading to added confusion and stress for all concerned. Some relief was given, at least, through the suspension of Ofsted school inspections, which one headteacher described as “like a cloud lifting”.

Prior to the pandemic, the use of online learning tools and EdTech in UK schools varied greatly. Following school closures, there was a surge in the provision and use of digital learning resources, such as the free online lessons provided by Oak National Academy and the increased use of BBC Bitesize, as well as online resources available through free applications such as Facebook (e.g. The Shed School) and YouTube (e.g. PE with Joe). From late April 2020, a UK government funded partnership with Microsoft and Google allowed schools to adopt either the Microsoft Teams or Google Classroom digital education platform, to facilitate synchronous (live) lessons, and set work and assessments, although a study of 1,233 senior leaders and 1,821 teachers in England by the National Foundation of Educational Foundation found that more training and development in effective remote learning approaches was needed, with particular topics including using virtual learning environments effectively, alongside video recording and editing.

What approaches did schools take during lockdown?

Globally

Schools around the world adopted a variety of approaches during national lockdowns, with many combining remote and in-person learning. Higher income countries tended to favour online and paper-based work packages according to UNESCO, UNICEF and the World Bank, while lower income countries favoured television programmes and radio transmissions. In a rapid review of 89 studies from around the world, the most frequently used technology during 2020 was synchronous collaboration tools (47%), such as video conferencing, followed closely by knowledge organisation and sharing tools (e.g. Learning Management Systems, 44%) and text-based tools (38%), such as discussion forums.

Technology that fosters interaction, both asynchronously and synchronously (live), have previously been found to increase student engagement, with examples of effective uses during the pandemic including group brainstorming and annotation, daily roll call videos, and the use of breakout rooms in online lessons for group work.

Some schools, however, were hampered in their use of online learning by pre-existing policies, such as the ban on mobile phones in Romanian schools or the data protection legislation in Europe. In cases where experiments or hands-on activities were needed, teachers explored alternative tasks, such as independent projects, having students take photos or make videos where they explained their thinking, and including home-based equipment or ingredients within task design. However, some governments banned students from conducting experiments at home, much to the frustration of teachers.

The small number of studies published to date which focus specifically on student ICT skills and knowledge report a lack of digital awareness, alongside a lack of self-organisation, with primary school students particularly in need of technical guidance. This was rectified in some cases by using one platform, rather than multiple applications, which helped keep information in one place and avoided the need for multiple login information.

Within the UK

Despite being a higher income country, many schools in the UK chose to use textbooks and other printed materials – often delivered to students at home – in order to help reduce equity issues and reliance on digital access, particularly for those within disadvantaged areas. The Understanding Society Longitudinal Study, found that almost half of students in Year 11 and 13 were not provided with school work, and that just over 50% of all students taught remotely did not have access to live lessons; about one third of secondary students had at least one online lesson a day, compared to 28% of primary students.

In September 2020, the Department for Education made it a legal imperative for schools in England to provide remote education for state school pupils during lockdown. The accompanying guidance stated that remote learning provision should be equivalent in length to the core teaching students receive in normal schooling and should include recorded or live direct teaching (from teachers or external providers such as Oak National Academy) and time for independent study. The minimum teaching requirements were 3 hours for Key Stage 1, 4 hours for Key Stage 2 and 5 hours for Key Stage 5.

A study of 5,582 parents in England revealed that while overall screen time increased for primary school children during the lockdown, their total learning time decreased from 6.3 hours to 4.1 hours per day. Parents of secondary school students reported a bigger drop, from 6.59 to 4.15 hours. Online classes accounted for 1.3 hours for primary students and 2 hours for secondary students on average, with around 40% of primary and 60% of secondary students spending less than 2 hours on non-class learning per day (e.g. learning with a tutor or completing set work outside of virtual lessons). The learning time further reduced for students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, especially for primary school students. Concerns have also been raised about international students, for whom live learning was not necessarily possible, due to time differences.

In Wales, a study in mid-2020 of 208 primary school teachers found that student learning and skill retention had regressed as a result of lockdown, with student wellbeing impacted, and some students becoming quite withdrawn. One reason suggested by respondents was the length of time it took for schools to set up online learning, as well as a lack of digital understanding and reluctance to use the national online learning platform ‘Hwb’ by parents.

In Northern Ireland, a large survey asked parents about the digital platforms schools used to provide online learning. It found that 67% of primary school parents and 87% of secondary parents reported schools using platforms such as Google Classroom or Seesaw, with 35% of primary parents using their existing school website, and 28% sending emails. The survey also found that 68% of parents were marking their children’s work, as there was no teacher feedback provided. Parents of students with special education needs and disabilities (SEND) reported that their children were more likely to struggle with understanding tasks and sticking to a routine.

UK-based research focusing on the experiences of vulnerable student populations has largely involved families of children with SEND, including smaller scale explorations of experiences during lockdown. A study of 339 parents of children mostly with conditions on the Autism spectrum conducted between March and May 2020, found that 37% of parents rated the support they received during lockdown as inadequate. Another study of 238 parents of children with SEND conducted in July 2020, found that while 68% of families had received educational resources from their school, just over half indicated that they were not appropriate for their child’s needs, citing a lack of differentiation and instructions on how to undertake the work as particular issues.

Studies with larger and more representative samples have been called for, including an exploration of the effectiveness of support provided to students following the end of lockdown. Limited research focused on other vulnerable populations, such as students from migrant and/or refugee backgrounds, has been undertaken elsewhere (e.g. Poland and Denmark) but not in the UK to our knowledge.

In Scotland, a national overview of how remote learning was undertaken in January 2021 reported that communication with parents by schools and local authorities about learning arrangements during lockdown was more effective in primary schools than in secondary schools, although some parents wanted more information about their child’s learning progress and increased contact with teachers. Videos pre-recorded by teachers were popular as they could be re-watched if required and used at any time.

Parents also reported that remote learning provision had improved after the first lockdown, with parents of primary school children reporting better learning structure and the introduction of new topics and concepts, as opposed to revision. An exploration of what worked better in the second and third lockdown, as a result of increased government and local authority guidance, alongside schools gaining more knowledge and experience in providing online learning, would be beneficial for understanding which remote teaching and learning approaches are most effective.

Teachers used a variety of methods for online assessment, with a particular focus on providing formative feedback. In secondary schools, this included the use of chat during live learning to ask questions, software such as Microsoft Forms for multiple-choice quizzes, oral assessments, and recorded verbal feedback from teachers. Teachers also encouraged the use of self-assessment, where students assessed their own progress against success criteria, as well as peer assessment, particularly making use of breakout rooms in live lessons to facilitate interaction.

Peer interaction, through assessment and collaboration, was found to be particularly important for student motivation and improving learning outcomes in the remote learning setting. However, as a result of the cancellation of GCSE and A Level exams in 2020, students were graded using teacher assessment, which in some cases resulted in a lack of student motivation to complete work throughout the year. Calls have been made to explore methods to implement digital technology in online examinations (as has been progressively implemented in South Australia since 2018), in a way that does not further disadvantage vulnerable student populations.

The digital divide

Despite the hard work, adaptability and innovation of teachers during the emergency remote education period, effective online learning has been hindered by unequal access to devices, internet connectivity and a suitable study space for learning. Major factors influencing this digital divide include socioeconomic status, age, region and country. There are disparities both between countries and within countries. For example, most of the 46% of the world’s population who lack internet access are from low-income countries but, even in high income countries, access to high-speed fibre internet varies, ranging from 79% in Japan to less than 5% in the UK.

In the UK, a report by The Sutton Trust found that at the start of the third national lockdown in January 2021, just 10% of teachers reported that all of their students had adequate access to a device or the internet for online learning (5% of state schools teachers and 54% of teachers in private schools). This report also indicates that the digital divide may have widened since March 2020, as the number of state schools reporting 1 in 5 students without device access increased from 13% to 18%. In Scotland, 48.2% of primary school-aged learners in a survey by Education Scotland reported that they had to share a device with someone else at home. The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) suggests that inequality in access to technology may be a contributing factor to the widening attainment gap between the most disadvantaged pupils and their classmates.

To help tackle the digital divide the UK Government launched the Get Help with Technology programme to deliver laptops, tablets, 4G routers and free mobile data to the most disadvantaged pupils and, as of March 2021, 1.26 million devices have been distributed. During the third lockdown, the four major UK telecoms providers removed mobile data charges for using the popular online learning platforms, Oak National Academy and BBC Bitesize. However, a May 2020 survey by the teachers’ union NASUWT found that the digital divide also affects teachers, with 36% of members reporting they did not have adequate IT equipment to provide online learning.

The role of parents and caregivers during lockdown

Evidence suggests that parental engagement in their children’s education is associated with improved academic outcomes. This was especially important during the pandemic, particularly for primary school-aged children, as students adapted to new technologies used for online learning and the loss of teacher and peer support. For online learning, maintaining motivation and engagement in school-age children is particularly challenging and parents reported a lack of focus and motivation and lack of contact with classmates as key challenges.

Parents have also had to provide assistance with solving technology problems such as navigating between multiple online learning platforms. However, some parents may lack the digital skills and knowledge required. Research from The Sutton Trust found that parents’ education levels impacted their level of confidence in supporting remote learning: while more than three quarters of parents with a postgraduate degree felt confident directing their child’s learning, fewer than half of parents with A level or GCSE level qualifications did so.

The added burden of home education placed on parents, in addition to other stresses such as work pressures, may have negatively impacted on parents’ mental health and increased strain on child-caregiver relationships. Parents have reported tension and discipline issues arising from role switching between parent and ‘teacher’. Despite this, one survey revealed around a quarter of parents reported relationships with their children had improved, and another survey found 53% of parents felt more engaged with their children’s learning than before lockdown.

Have schools altered their education practices since coming out of lockdown?

Globally

As schools around the world begin to reopen for in-person learning, stakeholders are unclear on what effect the extended period of remote education will have on the sector in the future. UNESCO cautioned against any potential for the education sector to ‘spring back’ to pre-pandemic norms, echoing the comment from the United Nations that the crisis has ‘stimulated innovation’ within the education sector. Although online education in the context of the pandemic has highlighted serious issues, such as the global digital divide, it has also presented an opportunity to build a more flexible, equitable, and inclusive education system.

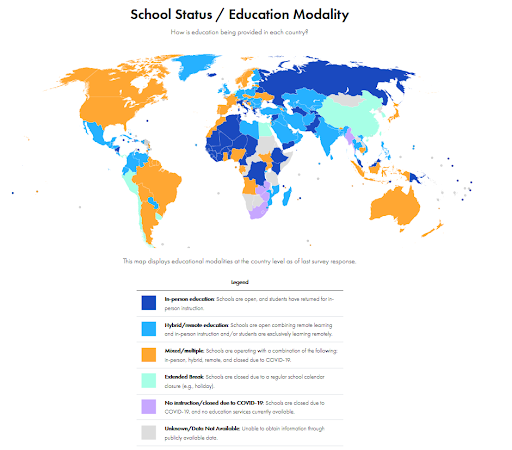

According to the COVID-19 Global Education Recovery Tracker (see map below), at least 51 countries have completely returned to in-person education, particularly within sub-Saharan Africa and the East Asian-Pacific region, but there are still more than 90 countries fully closed, or with students being taught via a range of hybrid learning modalities.

School status / education modality map as of 24 March 2021 (taken from the COVID-19 Global Education Recovery Tracker: Johns Hopkins University, World Bank & UNICEF, 2021)

Within the UK

The UK authorities in Scotland, England, Northern Ireland and Wales issued guidance stating that schools should continue to provide a hybrid learning model to allow continuity of learning between students learning in-person and anyone self-isolating. In addition, a range of measures have been introduced to support students with learning catch-up and to help schools adapt following extended closures.

For example, the Department for Education recovery package has allocated £700 million for in-person catch-up schemes, such as the National Tutoring Programme (NTP), and additional support for Oak National Academy to continue providing free online learning resources for catch-up in the 2021 summer term and holidays, although many experts consider the focus of summer holiday programmes should be on supporting children’s social, mental and physical wellbeing. Guidance for UK schools from the EEF on planning the 2021 academic year recommends teacher training on technology-enhanced and remote learning.

Conclusions

Despite the particularly stressful experiences of the past year, it is important not to discourage the wider use of online and blended learning in the future, despite mixed experiences of emergency remote education. Based on our look at the existing research, we suggest that plugging the following gaps in the evidence base would help to both deepen understanding of what children, parents, teachers and school leaders have experienced, as well as inform how practice could change.

Research gaps

Globally

We consider that further research is most urgently needed to:

- Find out how the use of online and blended learning impacted students in lower and middle income countries.

- Focus on the effects on vulnerable populations (as shown in the IPPO Living Map of systematic reviews of social science evidence), such as students with disabilities, homeless students, migrants and refugees, younger children, and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

- Examine the effects on teacher wellbeing, especially given the recent National Education Unit survey in the UK finding that 35% of teachers plan to quit teaching within the next five years.

- Take a longer term approach, since a rapid systematic review of K-12 research found that 44% of studies were of less than one month in duration, and often undertaken using a one-off survey.

- Explore the experiences of school leaders, teachers, students and parents, as much of the research published so far has focused on teachers.

- Examine the levels of school student digital competencies in detail.

- Examine the impacts of subject-specific interventions, particularly in non-STEM subjects, which currently dominate the evidence base.

Within the UK

Specifically within the UK context, research is needed to:

- Examine methods for online assessment, in light of the disruption and devastation caused by the cancellation of GCSE and A Level exams in the UK in 2020.

- Provide evidence on how schools in the UK used technology differently during the second and third lockdowns, and why.

- Focus on the experiences and views of students – and particularly those from vulnerable populations, e.g. migrants and refugees, SEND – as well as teachers, school leaders and families.

Authors of this topic snapshot

- Dr Melissa Bond, EPPI-Centre, Social Research Institute, University College London

- Faye Bolan, former Research Fellow at the UK Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST) and PhD student (University of Manchester)