The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of schoolchildren: a summary of early responses around the world

Many schools, local authorities and governments are grappling with how to handle the pressures on mental health amongst schoolchildren that have resulted from months of lockdowns and online schooling. How should they best spot emerging problems; how can young people best be supported? Here we share a snapshot of evidence and international experience to help decision-makers respond.

Summary of notable initiatives

- Our global evidence scan of initiatives to support schoolchildren’s mental health and wellbeing during the pandemic points to the importance of mobilising parents, friends, communities and online support to address the often-serious effects of the crisis on schoolchildren’s mental health.

- COVID‐19 can be seen as a ‘focusing event’, opening a window of opportunity for programmatic and policy shifts to improve the provision of non-academic school‐based services. These are widely seen as critical to the support of children’s mental health, which has been negatively affected by school closures and other social impacts of the pandemic.

- The Mental Health Foundation’s study on the impacts of lockdown in Scotland suggests children may benefit from the opportunity to validate their experiences of lockdown with their peers.

- A global review of impacts of mass disruption (including COVID-19) on the wellbeing and mental health of children and young people, commissioned by the Welsh government, found that community support programmes both increase children’s wellbeing and reduce their mental health difficulties, as does social support from parents and peers.

- In the Netherlands, provision has been made to support children whose home environment is not conducive to at-home learning by providing teaching and counselling at libraries or schools. Some schools are offering programmes to boost their students’ confidence and help their ability to structure learning at home – also including parents in these programmes.

- In New Zealand, the government has provided online mental health support designed to encourage parents to talk to their children about their mental health and wellbeing during lockdown.

- In Ontario, Canada, provincial government funding has been provided for mental health support for school students upon their return to school after lockdown – enabling school boards to hire additional staff and develop tailored support programmes.

- A study of COVID-related mental health assistance in elementary and middle schools in a city in Jiangsu, China, identified positive effects from providing a psychological hotline, publishing online mental health ‘micro-classes’, and posting mental health tweets.

UK focus: multiple warnings that children’s mental health is worsening

Even before the pandemic emerged, there was considerable evidence of reduced wellbeing among young people – ranging from higher levels of stress and anxiety to symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). A five-year study by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) (published Oct 2020) found that nearly one-third (31%) of young women aged 16-24 reported some evidence of depression or anxiety in the year 2017/18 – 5% higher than both the previous year and five years earlier.

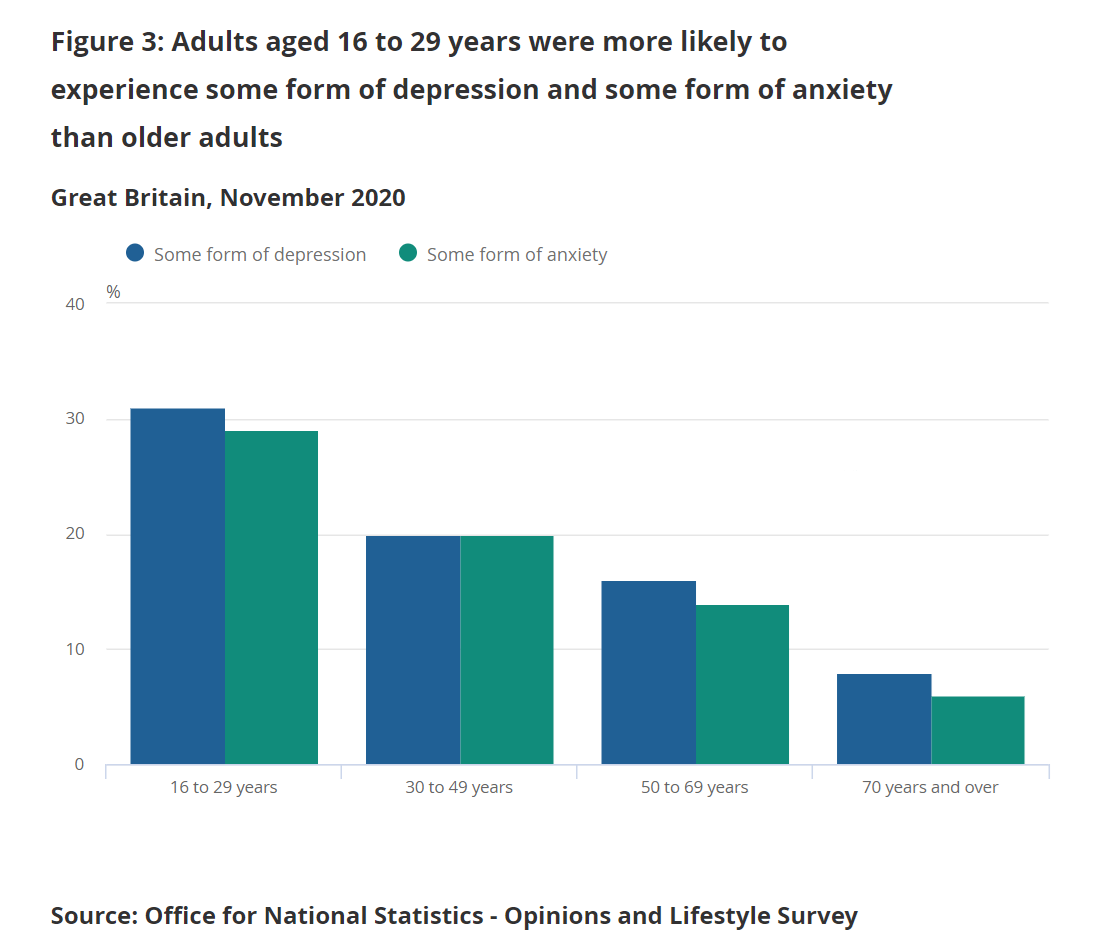

In a related ONS report (June 2020) on the initial social impacts of COVID-19, young people aged 16-29 who said their wellbeing was affected were much more likely to report that it was making their mental health worse (42%) and making them feel lonely (51%) than people in older age groups.

A study of child mental health in England before and during the COVID-19 lockdown (Newlove-Delgado et al, Jan 2021) identified a significant overall rise in probable mental health problems among children aged 5-16, from around one-in-nine in 2017 to one-in-six in 2020 (boys up from 11.4% to 16.7%; girls up from 10.3% to 15.2%). In the 17- to 22-year-old age group, both before and during the pandemic young women had the highest prevalence of probable mental health problems (27·2% in July 2020, compared with 13.3% of young men), suggesting they should remain a group of particular policy concern.

The study also highlighted issues of access to mental health support for young people. Almost 45% of those aged 17-22 with probable mental health problems reported not seeking help because of the pandemic, and there has been a sharp decrease in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) referrals. Some 21·6% of children and 29·0% of young people with probable mental health problems reported having no adult at school or work to whom they could turn during lockdown periods.

During the first lockdown, a survey by MCR Pathways of 1,347 care-experienced and disadvantaged young people in Scotland (ages 13-18) found that two-thirds (66.8%) were feeling low, more anxious and stressed since lockdown, with 26.5% experiencing significantly disrupted sleep. In addition, more than a quarter reported having caring duties that impacted on their capacity for home learning.

There have been many warnings that school closures are causing wider ‘collateral damage’ to the mental health of children, who are at lower risk of COVID-19 but disproportionately affected by the consequences of intervention measures (including a lack of school-based mental health and wellbeing supports). In January 2021, a coalition of UK child health experts called for an independent commission to develop a cross-government strategy to help children and young people through the lingering effects of COVID-19. ‘At present we have piecemeal solutions and stop-gap measures,’ the experts wrote in a letter to the Observer newspaper, adding that children’s welfare ‘has become a national emergency’. They reported that 1.5 million children under 18 in the UK would either need new or additional mental health support as a result of the pandemic – with a third of these being new cases, according to the Centre for Mental Health.

After the first lockdown, a number of UK mental health charities recommended that the primary focus as children returned to school should be on promoting wellbeing and re-integration, rather than academic achievement.

Global focus: the relation between wellbeing and (future) learning

Evidence on the direct impact of lockdown on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people yields mixed findings, with some studies indicating an increased likelihood of PTSD symptoms in quarantined children. Overall, studies point to increased levels of distress, worry and anxiety – with likely reasons including heightened feelings of loneliness, and worries about returning to school, missing school, and the future.

A systematic review of global evidence by Nearchou et al (Oct 2020) found that COVID-19 has an impact on youth mental health, and is particularly associated with depression and anxiety in adolescent cohorts. A systematic review of research into the impacts of quarantine and isolation on the psychological wellbeing of children (Memon et al, Oct 2020) found the most common diagnoses are acute stress disorder, adjustment disorder, grief, and PTSD.

The evidence points to some family contexts where experiences of lockdown are particularly difficult for children and young people. These include families where parents/carers are key workers, are younger, live in poor conditions (e.g. confined housing, noise, lack of outdoor space), or have a history of mental/physical health conditions. A non-systematic global review (Marques de Miranda et al, Sept 2020) identified particularly high rates of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic symptoms among children from more vulnerable groups – suggesting that mitigation actions should prioritise these groups.

Other potential impacts on schoolchildren’s mental health, highlighted by Professor Brad Blitz at the Institute of Education (IoE), include the stigma of not possessing a laptop during periods of remote learning; food shortages and nutritional deficiencies brought on by a lack of school meals; lack of physical exercise; and the impact of loss and mourning within families.

‘It is important to highlight that children’s mental health during the pandemic should be presented as a critical issue and policy option, weighted against the other key issue of transmission,’ Blitz said. ‘While the loss of schooling is seen as a long-term issue, in my opinion children’s mental health is – incorrectly – not seen as a chronic problem.’

There is evidence that engagement with the curriculum has been disrupted for many children and young people, including those without sufficient digital access, physical space and other resources to support their learning. Academic articles by Lee (June 2020) and Hoffman and Miller (Aug 2020) highlighted the impact of school closures for children and adolescents with mental health needs – in particular, a lack of access to the resources they usually have through schools. According to Lee: ‘School routines are important coping mechanisms for young people with mental health issues. When schools are closed, they lose an anchor in life and their symptoms could relapse.’

While some of the conditions for poor wellbeing (e.g. confined housing, food shortages, no laptop) have an immediate negative effect on learning as children cannot access online teaching, they may also have a longer-term effect if behavioural problems limit these children’s ability to do well in school, and potentially disrupt learning for others too.

What can be learned from other instances of severe social restrictions?

A systematic review by Araujo et al (Sept 2020) of studies assessing the impact of epidemics and other social restrictions on mental and developmental health found the more adverse the experiences for children, the greater the risk of developmental delays and health problems in adulthood, such as cognitive impairment, substance abuse, depression and non-communicable diseases.

A rapid systematic review by Loades et al (June 2020) looking at studies of children’s loneliness relevant to COVID-19 found the duration of their loneliness is more strongly correlated with mental health symptoms than its intensity.

A review of global literature on the impact of mass disruption on the wellbeing and mental health of children for the Welsh government (Williams, Sept 2020) – which includes the impacts of both COVID-19 and previous international disasters – found that older children and those with special needs are more likely to suffer related mental health issues, including PTSD and depression. It also found that community programmes both increase children’s wellbeing and reduce their mental health difficulties, as do social support from parents and peers.

A literature review by Karki (April 2020) of lessons from past pandemics and epidemics concluded that education systems should immediately and substantially activate a response plan that ensures children retain their connection to education.

Initial responses: boosting non-academic support in schools has been a priority

Our survey of research into the impact of COVID-19 on secondary schoolchildren’s wellbeing highlights important policy questions that need further investigation, including: how best to identify and interpret mental health problems among this cohort; how much schools can be expected to provide support themselves; what are the best mechanisms for linking this support with other specialist services; and how best to support parents in a way that improves their children’s mental health outcomes.

COVID‐19 can be seen as a ‘focusing event’ (Kingdon, 2010), opening a window of opportunity for programmatic and policy change that improves the provision of non-academic school‐based services and supports in future. While the social and emotional needs of children and their families were at the forefront of teachers’ minds when students returned after the first period of lockdown (Moss, June 2020), there is acute, widespread need for these non-academic supports to be provided in schools (Hoffman & Miller, Aug 2020).

In Ontario, Canada, a total of $12.5 million (£7.2 million) of provincial government funding has been provided for mental health support for school students upon their return to school after lockdown – enabling school boards to hire additional staff and develop tailored support programmes.

Scotland’s government has pledged to develop and deliver a new mental health training and learning resource, which will be available to all school staff by summer 2021. This resource will include learning for school staff to respond to the impact of COVID-19 on children and young people’s mental wellbeing. The MCR Pathways Scotland survey’s recommendations include ensuring education is provided on a full-time basis, that schools offer a recovery curriculum, and that disadvantaged young people are systematically and comprehensively consulted throughout the formation of all recovery and rebuild plans.

According to Professor Melanie Ehren , director of LEARN! at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, when Dutch schools reopened between the first and second lockdowns, an ongoing study of learning loss and catch-up programmes showed many pupils had lost some of the strategies for in-school learning, as well as their confidence to do well in school – particularly when faced with high-stakes examinations. Schools reported behavioural problems which also affected the learning of other pupils in the classroom. In response, some schools began offering programmes to boost their students’ confidence and help their ability to structure learning at home, also including parents in these programmes.

Increased stress levels among schoolchildren have also been related to the fear of getting infected when returning to school, or (where children had positive experiences of homeschooling) anxiety about renewed interaction with peers, and peer pressure.

Supporting mental health at home: the importance of peers and parents

Our evidence sweep of potential responses suggests schools should consider population-based mental services in which supports are tailored to promote the overall psychological wellbeing of all students, as well as providing specific support within the school environment. In New Zealand, the government has provided online mental health support designed to encourage parents to talk to their children about their mental health and wellbeing at home during lockdown.

The Mental Health Foundation’s study on the impacts of lockdown on the mental health of children and young people in Scotland (Sept 2020) found that children may benefit from the opportunity to validate their experiences of lockdown with their peers, and should continue to receive clear communication about the pandemic, including on their return to school.

The National Youth Agency contended (Aug 2020) that poor diets, lack of physical exercise and increased poverty all exacerbate the problem of childhood obesity and its emotional and mental health consequences – but that public health messages are not well aimed at young people. It recommended keeping support services for young people open during lockdown where safe to do so (with youth services classified as an essential service); mobilising youth workers as critical workers alongside health professionals with significant investment in training and upskilling; and providing clear and ongoing public health messaging designed in collaboration with (as well as for) young people.

It also appears that people in Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities have died from COVID-19 complications at a higher rate than their counterparts, so an understanding of specific needs and challenges in these communities is necessary to provide high-quality support (Phelps and Sperry, Aug 2020).

Assessing the efficacy of interventions both in and out of school

The appropriateness of school-based programmes for identifying mental health difficulties was found to vary by condition – with time, resource and cost concerns the most common barriers to feasibility across models and conditions (Soneson et al, July 2020).

A systematic literature review of the effectiveness, feasibility and acceptability of interventions and support tools for school staff to adequately respond to young people who disclose self‐harm (Pierret, Dec 2020) found these tools are highly effective in terms of an increase in knowledge, skills and confidence of staff in responding to self-harming youth. Acceptability was good, with high levels of satisfaction and perceived benefit among staff.

In terms of specific responses, a study of COVID-related mental health assistance in elementary and middle schools in a city in Jiangsu, China (Quan, Sept 2020) identified positive effects of providing a psychological hotline, publishing online mental health ‘micro-classes’, and posting mental health tweets.

An academic paper by Seymour et al (Oct 2020) outlined important practice lessons gained from adapting an education re-engagement programme to respond to the COVID-19 lockdown in Greater Brisbane, Australia. These highlight ‘the compounding effect of digital inequality on vulnerable young people who are already disengaged or disengaging from secondary education – and the necessity for a reflexive, agile and adaptable practice response’.

Shedding more light: notable ongoing research on children’s mental health levels

- The DEPRESSD Project: a global ‘living systematic review’ of mental health during COVID-19.

- Impending evaluation of the CAMHS In-Reach to Schools Pilot Programme, which aims to build capacity (including skills, knowledge and confidence) in schools to support pupils’ mental health and wellbeing.

- The short- and long-term impacts of school closures and other isolation measures in childhood on physical and mental health (Viner et al).

- Psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: identifying mental health problems and supporting wellbeing in vulnerable children and families (Goozen).

- Potential impact of a pandemic on the mental health of young people aged 12-25 (O’Reilly et al).