Roundtable report: using evidence to tackle the long-term causes of homelessness in more systemic ways

In the second of IPPO’s policy roundtables, we discussed the future of homelessness in each UK nation in light of the many dramatic interventions around the world during the pandemic

Geoff Mulgan

The International Public Policy Observatory’s latest roundtable, on homelessness, welcomed some of the leading policymakers from across the UK, alongside researchers, international experts and voluntary organisations. The mood of the meeting combined satisfaction with the scale of recent responses on this issue with anxiety about the future.

When the COVID-19 crisis began last spring, many governments moved with extraordinary alacrity. Across the UK – within a few days – the vast majority of people living on the streets had received accommodation offers. Hotels were mobilised and emergency accommodation provided on an unprecedented scale. In England alone, some 33,000 people were provided with emergency accommodation by the end of November 2020, of whom more than 23,000 received settled accommodation or supported housing – a temporary solution to homelessness that no one would have thought possible a year ago.

Our roundtable confirmed the sense that there has been rapid and dynamic action right across the UK, including significant allocations of money. We also heard from the United States, which has had a poor record on homelessness in recent years, but where cities and states have also been spurred into unprecedented levels of action – whether by effectively providing a universal basic income for children, or by offering emergency accommodation.

What to do next

The big issues for 2021 are really about what to do next. In the short run, there are questions over how to handle the exit from the COVID crisis, including how much priority to give homeless people in relation to vaccines. In the medium term, there are serious concerns about the likely social and economic dynamics in 2021 – including potentially high levels of unemployment and household debt, exacerbated by factors such as the end of leniency on rental arrears and worsening mental health stresses.

All might be expected to raise the flow into homelessness, thus increasing the importance of homelessness prevention programmes. The same is true of how other factors are managed, such as support for prison-leavers or those moving out of National Asylum Support Service (NASS) accommodation, which has often led people to end up on the streets.

Then there are the longer-term issues of homelessness and housing policy. Some of these are relatively straightforward, including the long shift away from traditional shelters towards more personal accommodation. While this trend is generally welcomed, it requires a significant expansion of social housing which has proved hard in the UK – in part because of the combination of housing shortages and a rising population (very different to other parts of Europe, where populations have been static or falling).

How to weave together coherent, evidence-based policies

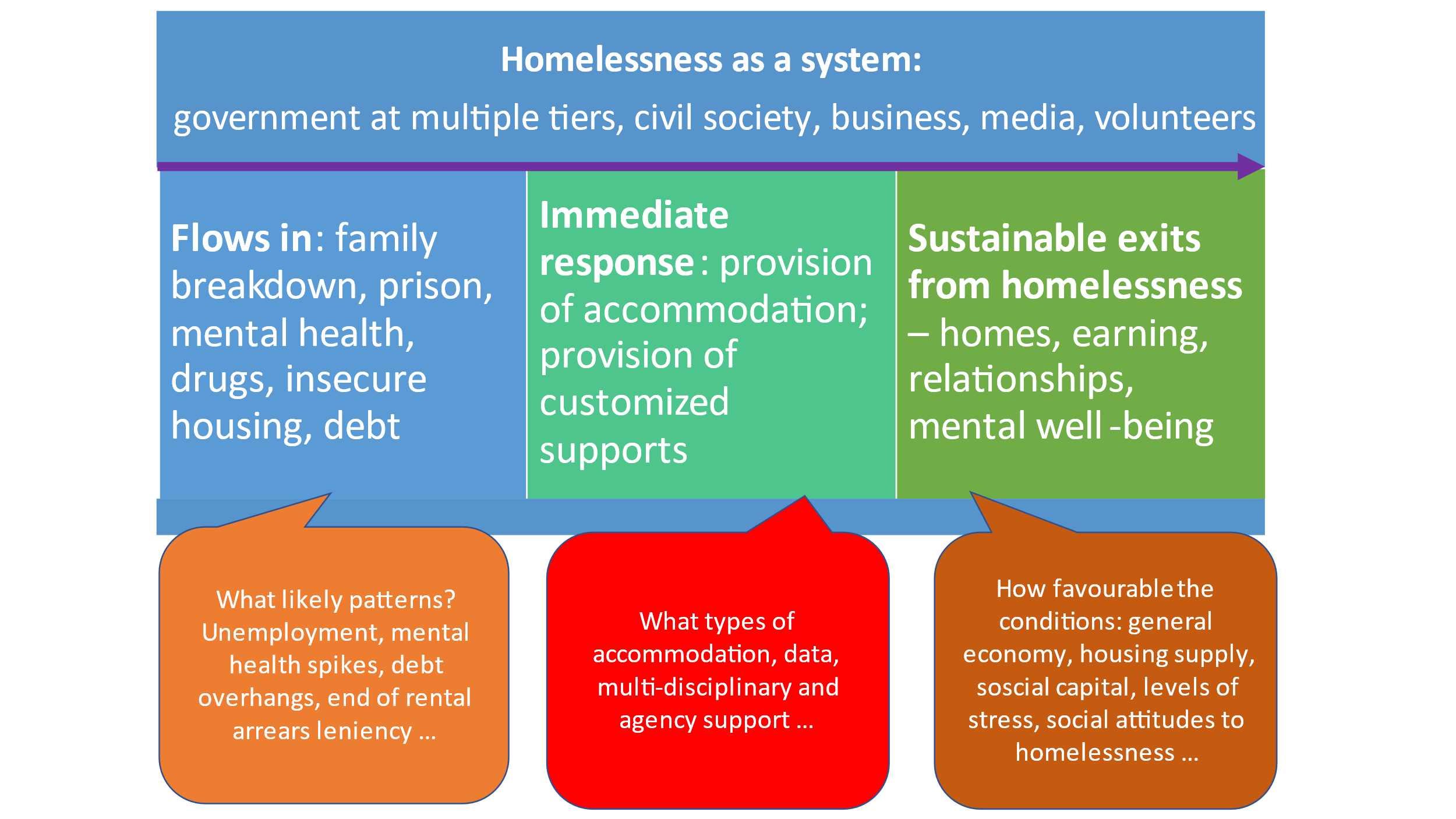

The more strategic question raised by the roundtable is how to weave together coherent, evidence-based policies on each aspect of homelessness; namely:

- The upstream flows into homelessness resulting from many different factors, from family breakdown to leaving the army or prison without the right support.

- Support in real time, including accommodation and multidisciplinary teams to help with other issues (from mental health to drink or drugs).

- Coherent plans to exit homelessness (i.e., permanent accommodation plus other supports to help with jobs and relationships).

The 1998 Rough Sleeping strategy for England (which I was involved in designing with the Social Exclusion Unit) aimed to do that in a different era, and led to pooled budgets, combined teams and ambitious targets, as well as an active programme on prevention. A year later, Louise Casey was recruited to run the Rough Sleepers Unit and oversee the strategy’s implementation with a £200 million budget and a target of reducing the number of rough sleepers in England by two-thirds within three years – a goal that was achieved a year early.

The key point was to understand homelessness in more systemic ways – recognising that the lack of a home is often the result of many factors, and often a symptom rather than the fundamental problem. This was challenging for a previous generation of homelessness organisations that saw their role solely as providing temporary accommodation and food. It is now more widely understood that shelter is a necessary but not sufficient condition for ending homelessness.

Systemic approaches require political will and better data

The diagram above sums up some of the issues and (at the bottom) challenges that are now being faced – both upstream in terms of flows into homelessness, and downstream in terms of sustainable exits.

All systemic approaches require political will and capability. But they also require good organisation of data (an issue raised by several participants at the roundtable) as well as more fine-grained evidence. On the data front, there are interesting developments in Canada and the US that make use of much more detailed data (Crisis is now introducing a similar project in the UK, in Newcastle and Oxfordshire). Meanwhile in China, local governments are implementing policies on extreme poverty that are focused on individual households rather than aggregated data.

Similarly, we need better ways of organising money – to capture the full range of costs (and benefits and impacts) over long periods of time. Most funding in this field is still annual, although there have been some efforts to use evidence to guide longer-term investments, whether in social impact bonds linked to homelessness or by looking at public spending ‘multipliers’.

While none of this is particularly easy, it isn’t rocket science either: if there is the political will, there is no obvious reason why large-scale homelessness should be a norm. The COVID crisis has shown how much can be achieved in the short term with sufficient will. The next challenge will be to apply a similar determination to the long-term causes of homelessness.

Read more on this subject in IPPO’s topic snapshot by Professor Nicholas Pleace from the University of York, and in this view from Finland by Juha Kaakinen, CEO of the Y-Foundation

Useful links shared by roundtable participants

- The Finnish Homelessness Strategy: An International Review (2015)

- The National Federation of ALMOs: Can social housing rebalance the homelessness equation?

- UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CACHE): The COVID-19 crisis response to homelessness in Great Britain

- Institute for Social Policy, Housing and Equalities Research: Destitution in the UK 2020 (Technical Report, Heriot Watt University)

- Centre for Homelessness Impact : Accommodation-based programmes for individuals experiencing or at risk of homelessness (a systematic review)

- The Everyone Home collective in Scotland

- St Mungo’s: Housing and Health: Working together to respond to rough sleeping during Covid-19

- Homelessness, Housing Precarity and Disaster Network: International research agenda and framework as a Converge Working Group

- Telescope: Connecting policy and social sectors to build a better future (series of on-line programmes)

- University of Portsmouth (in collaboration with University of Sussex and St Mungo’s): New project on homeless migrants and COVID-19

Housing and homelessness data from the Scottish Government

- Homelessness: At the start of the pandemic, SOLACE (Scottish Association of Local Authority Chief Executives) and the Scottish Government set up weekly/monthly data collections on Homelessness including applications and use of temporary accommodation. These are published weekly in Vulnerable Children & Adult Tableau Data Tables, alongside other indicators.

- The Scottish Housing Regulator: Also publishes monthly dashboards showing the impact of COVID-19 on the social rented sector, including homeless applications and use of temporary accommodation.

- Housing Market: The impact of COVID-19 on the housing market in Scotland is assessed in the Quarterly Scottish Quarterly Housing Market Review (latest edition here).

- Coronavirus Scotland Act: We have been pulling together information from a range of data sources to assess the impact of COVID-19 on tenants and landlords, informing decisions on eviction protection. This information was published in the Coronavirus Monitoring Reports.