Reflections On 25 Years of Devolution in Scotland

This blog is part of an IPPO series looking at how policymaking across England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland has been shaped by devolution since 1999.

Nicola McEwen

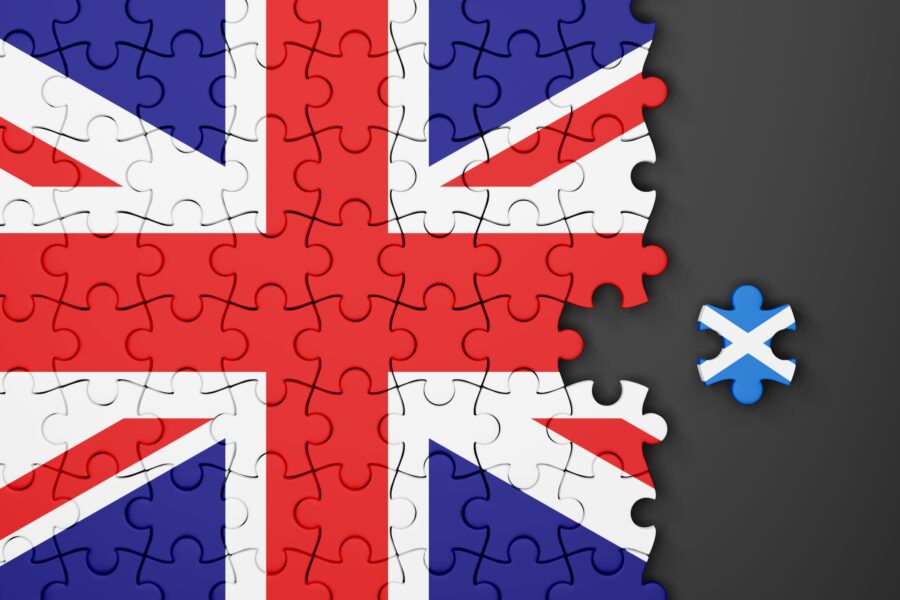

As the Scottish Parliament turns 25, we consider its evolution and place in public life in Scotland. Recent reforms both to the devolution settlement and to UK territorial governance present new challenges to the devolved institutions that could constrain policy ambition in the years to come.

High Expectations

In May 1999, Scotland voted in a new parliament and government. There were high expectations about the positive differences it could make to the NHS, education, the economy and Scotland’s voice in the UK. Trust in the new institutions was also high; according to the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey (SSAS), 8 in 10 Scots trusted the new parliament to work in Scotland’s best interests ‘just about always’ (26%) or ‘most of the time’ (54%). The comparable figures for trust in the UK Government to do likewise were 3% and 30% respectively.

In the 25 years since then, the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government have become firmly embedded in political life in Scotland, and are arguably the focal point of public discussion, expectation and debate. In an era where trust in politics is often questioned, the devolved institutions continue to command relatively higher levels of trust than their counterparts in Westminster and Whitehall, albeit not quite at the levels seen at the parliament’s foundation. In the latest available SSAS data, 66% trusted the Scottish Government to act in Scotland’s best interest just about always or most of the time, despite diminishing confidence in the public services over which it (mainly) governs. Just 22% recorded the same degree of trust in the UK Government.

For much of the last quarter century, devolution in Scotland has been marked by relative stability, notwithstanding the period leading to the independence referendum in 2014. The devolved institutions became synonymous with landmark policy innovations, especially with respect to regulatory and distributive policies.

Examples of the former include the ban on smoking in public places, introduced by the Labour-Liberal Democrat administration in 2006, and Minimum Unit Pricing for alcohol, implemented in 2018 by the SNP administration, both introduced as public health interventions. Examples of the latter include covering the costs of prescriptions, personal care for the elderly, bus travel for those who are under 22 or 60+ years, and tuition fees for home and (prior to Brexit) EU students, with these services described as ‘free’. The cumulative effect of these policies has been to accentuate the divergence in citizens’ entitlements depending on where in the UK one lives.

Reforming Devolution

The Scottish devolution settlement was reformed in 2012, when we saw a modest increase in fiscal autonomy. The 2016 reforms that followed originated in the cross-party Smith Commission, set up in the immediate aftermath of the 2014 independence referendum. The Scotland Act (2016) represented a marked increase in the powers and responsibilities of the Scottish Parliament. These enhanced the ability of the Scottish Government to introduce redistributive policies, especially in relation to tax and social security. This has led to further policy innovations and divergences, not just with respect to citizen entitlements but also to obligations.

Most notably, the Scottish Government now has responsibility for setting the rates and thresholds for taxes on non-savings, non-dividend income above the personal allowance (the latter is set by the UK Government). This power has been used to create a new 6-band tax structure such that the lowest earners living in Scotland pay less than their UK counterparts, with those earning above £28,850 paying more. As well as its potential redistributive benefits, taxing higher earners is also a tool for raising additional revenue for public services. However, the effectiveness of income tax as a revenue-raising tool is doubly constrained by the scope of fiscal devolution and expected behavioural changes. At least some high earners may shift more earnings into savings or dividends (not devolved), shift their residence status away from Scotland, or reduce their working hours to avoid paying more taxes on their earned income, substantially reducing the revenue-generating potential of tax rises.

The 2016 reforms also brought significant new policy responsibilities in social security. Certain categories of benefits were devolved, such as disability, industrial injuries and carers’ benefits, alongside the power to top-up UK benefits and introduce new benefits in areas not otherwise connected to social security benefits delivered by the UK Government. Since then, a new agency has been set up – Social Security Scotland – that has tried to instil a new culture in supporting claimants. Fourteen Scottish benefits have been introduced, including seven new benefits. Among these, the flagship Scottish Child Payment is thought to have made a key contribution in reducing the number of children living in poverty.

But these distinctive entitlements of the new Scottish social security system have left a gap between devolved spending and the money that the UK Government transfers to the Scottish Government to cover its social security responsibilities, as the latter are based on spending on equivalent benefits in England and Wales. And that gap is set to grow; the Scottish Fiscal Commission estimates a funding gap of £225 million in 2023-24, rising to £694 million in 2028-29, putting pressures on other areas of public spending.

Brexit and Devolution

Another critical moment in Scotland’s devolution journey was the 2016 Brexit referendum. The UK decision to leave the European Union took place without the consent of the people of Scotland, who had voted by 62% to 38% in favour of the UK remaining in the European Union. Brexit also posed new challenges to devolution. EU law had provided regulatory scaffolding that limited, but did not eliminate, policy divergence between the constituent territories of the UK. As Prime Minister, Theresa May was concerned that leaving the EU and especially the Single Market might generate greater policy divergence between the UK and devolved governments that would create new barriers and new costs for businesses trading across the UK.

A variety of mitigating interventions were made. Some, such as Common Frameworks, were developed in collaboration with devolved governments, with agreed processes for cooperation in devolved policy areas that had hitherto been subject to EU law. The United Kingdom Internal Market Act, by contrast, was a more unilateral initiative, passed by the UK Parliament despite fierce opposition from the devolved institutions.

The UKIM Act introduced market access principles that limit the reach and impact of laws caught up in its scope, unless an exclusion is negotiated. Thus, any law passed by the Scottish Parliament that regulates the characteristics, production, packaging, labelling, standards, certification, or any other pre-sale requirement of a good, cannot be imposed on goods entering the Scottish market from other parts of the UK. The UK Government’s own impact assessment of the legislation noted, ‘where parts of the UK pursue separate policies, the scale of the intended public benefit of local measures might not be fully realised due to the more limited number of goods and services to which the policy applies’.

The most controversial instance to date saw the Scottish Government abandon its Deposit Return Scheme months before its planned implementation, after securing only a temporary and limited exclusion that excluded glass. Proceeding without an exclusion would have put Scottish producers at a competitive disadvantage. Other policy areas affected relate to public health and animal welfare. The UKIM Act privileges free trade and regulatory alignment across the UK over the regulatory autonomy of devolved institutions. It has been one of the most significant and controversial interventions to affect the operation of devolution since 1999 and its introduction without devolved consent has contributed to the deterioration of the relationship between the UK and devolved governments during recent years.

Looking Ahead

The next 25 years look set to begin with a new UK administration, which could offer an opportunity to ease some tensions and improve relationships. But many of the complexities and challenges that Brexit introduced to the operation of devolution will remain whoever governs in Westminster.

The fiscal challenges facing the Scottish Government are also likely to intensify in the years to come. This is a consequence of the powers and responsibilities in tax and social security devolved in 2016, and the political choices associated with them. And the challenges are compounded by demographic pressures arising from an ageing population which, together with medical advancement, will likely see an increasing proportion of the Scottish Government’s budget taken up by the NHS, leaving little for the many other challenges on the horizon, from climate change to broader public service provision.

All of this suggests that whichever party wins future Scottish elections, the Scottish Government will have little choice but to confront difficult policy choices and trade-offs. The Scottish Parliament’s next quarter century may prove to be more challenging than its first.