Range and variety in models of public inquiry: how to stimulate innovative inquiry design, process and practice

In our inquiries workstream, IPPO encourages an evidence-based debate about the benefits of adopting an innovation-led approach to the design and delivery of public inquiries. This position paper is authored by Professor Matthew Flinders, Professor Sir Geoff Mulgan and Dr Alastair Stark

Executive summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested the resilience of governments around the world to respond to and cope with a virulent challenge. In many countries, as the immediate short-term crisis moves towards a science- and data-led containment and control strategy, the political agenda is now shifting towards a focus on accountability and lesson-learning.

The multi-levelled nature of these scrutiny processes is reflected in (for example):

- the Scottish Government’s publication of a public consultation on the aims, process and objectives of a COVID-focused public inquiry;

- the UK Government’s commitment to establish an independent public inquiry in the spring of 2022; and

- the decision by the World Health Assembly to call for the World Health Organisation (WHO) to conduct ‘an impartial, comprehensive, and independent evaluation’ of ‘the experience gained and lessons learned from the WHO-coordinated international health response to COVID-19’.

It is in this context that the International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO) has decided to launch a workstream to provide evidence-based insights about the design and delivery of public inquiries. We have already submitted evidence to the Scottish Government, and now publish this position paper with the aim of supporting research-users across the UK and beyond – politicians, public officials and the public – by nurturing an evidence-based debate about the benefits of adopting an innovation-led approach to the design and delivery of public inquiries.

A new way of thinking about public inquiries

The existing research base on the use of public inquiries raises significant concerns about their ability to ‘learn from the past’. The core insight from this body of scholarship is that:

- public inquiries tend to adopt too narrow and legalistic an approach;

- they often face conflicting goals and priorities; and

- they regularly become drawn into an over-emphasis on the allocation of blame, to the detriment of a more mature and future-focused emphasis on lesson-learning.

Indeed, as this week’s ‘Coronavirus: Lessons Learned to Date’ report from the House of Commons Science & Technology and Health & Social Care Committees has demonstrated, even the most careful attempts to focus on positive lesson-learning risk becoming embroiled in blame-focused public debates.

In response, IPPO’s paper seeks to encourage a constructive debate about the benefits of adopting an innovation-led approach to public inquiries by focusing on both ‘innovative inquiry design’ and ‘innovative inquiry processes and practices’. The former element relates to initial design decisions, and the latter element to issues of ongoing process. When taken together, these serve to reveal a choice of approaches to public inquiries that is rarely exposed, acknowledged or considered. This is a completely new way of thinking about public inquiries.

Structure of this paper

This IPPO position paper is divided into five interrelated sections:

- The first section revolves around definitional clarity and seeks to identify the main characteristics of a public inquiry. Of particular significance is the decision to distinguish between legislative and parliamentary committees, on the one hand, and independent public inquiries, on the other hand.

- The second section explores the existing research base on the governance and impact of public inquiries. This leads to a focus on six key concerns or inquiry challenges.

- The third section builds on the identification of these challenges by exploring the opportunities for innovation through a focus on ‘innovative inquiry design and inception’ and the development of a typology of design options. The great risk with a focus on initial design is that it overlooks the significance of subsequent processes and delivery.

- It is for this reason that the fourth section focuses on ‘innovative inquiry processes and practices’.

- The fifth and final section reflects on why the content of this report matters.

Section 1: What is a public inquiry?

A public inquiry is a high-level review conducted with a significant level of political independence into ‘matters of public concern’. 1 The term ‘public inquiry’ can refer to a broad range of procedures, the main distinction being between statutory and non-statutory inquiries. 2 There are four main forms of non-statutory public inquiry: non-statutory ad hoc inquiries (including independent panels); committees of Privy Counsellors; Royal Commissions; and departmental inquiries. 3

The main form of statutory public inquiry operates under the Inquiries Act 2005 which establishes a statutory framework for the appointment of the chair, the taking of evidence, the production of a report and recommendations, and the payment of expenses. The 2005 Act replaced the Tribunals of Inquiry (Evidence) Act 1921 which was perceived as inflexible and, as a result, was rarely used and forms of non-statutory inquiry prevailed. The 2005 Act sought to make statutory inquiries simpler and more flexible, thereby making it the default option.

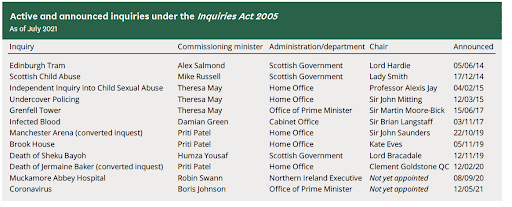

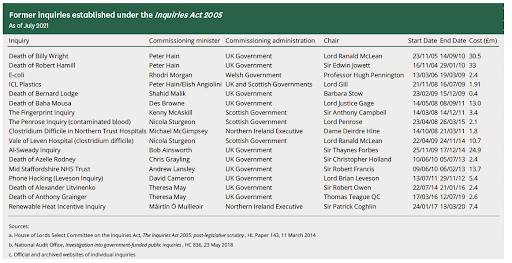

Twenty-eight inquiries have been established under the 2005 Act, of which 10 are ongoing (see Appendices A and B). Three more public inquiries have been announced (on Muckamore Abbey Hospital, a UK-level inquiry into Coronavirus, and a Scottish COVID inquiry ) but do not yet have a chair or terms of reference. The Inquiry Rules 2006 provide a number of detailed requirements for the administration of inquiries. 4

Immune to political influence?

Public inquiries should not be confused with legislative or parliamentary inquiries. These are undertaken by, for example, select committees in both the House of Lords and House of Commons and by scrutiny committees in the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Parliament. To date, a wide range of select committees have undertaken more than 60 COVID-related inquiries. In the House of Lords, a focused COVID-19 Committee was established in order to provide a clear focal point for scrutiny and avoid duplication. Public inquiries are explicitly designed and intended to be very different to parliamentary committees, in the sense that they are theoretically independent of the government of the day and immune to political influence (discussed below).

As Christoph Meyer and his colleagues underline, public inquiries can also be undertaken or co-ordinated by non-governmental actors, such as the Carnegie Commission on the Prevention of Deadly Conflict or the Harvard/LSHTM panel into Ebola to prevent future pandemics. 5 Such knowledge-broker-led inquiries, possibly convened by an organisation like the Wellcome Trust but bringing together a range of organisations, could play a major role in fact-finding and lesson-learning.

Given that the National Audit Office concluded that the average time between the onset of an incident and the creation of a statutory inquiry is on average around six years, it is also possible to suggest that knowledge-broker-led inquiries are more agile and could start sooner. 6 With public health expertise being critical to understanding the sequencing and success of COVID-related decisions a knowledge-broker-led inquiry may offer distinct benefits, while also serving to depoliticise the process to some extent.

A powerful example

Meyer suggests that the Harvard-LSHTM Independent Panel on the Global Response to Ebola offers a powerful and generally positive example of a non-governmental inquiry. Drawing together a wide range of expertise from academia, civil society and the third sector, the panel took a ‘global, system-wide view’ to ensure the necessary policy changes to prevent outbreaks in the future. In addition to leading to a restructuring of the WHO to increase scientific capacity, the panel served to create political will and engagement, catalysing new partnerships and regulatory mechanisms to advance emergency research and development. 7

Only government ministers, from either the UK or devolved administrations, can establish a formal public inquiry under the 2005 legislation. Once an inquiry has been announced, the minister must make a statement to the relevant parliament, as soon as is reasonably practical, indicating who will chair the inquiry and their terms of reference.

Statutory inquiries are established initially by the relevant department but, once established, are formally independent with their own secretariat. The Ministry of Justice has responsibility for the Inquiries Act 2005 and the Inquiry Rules 2006, and advises on the application of both. The Cabinet Office is responsible for advising as to whether a public inquiry should be established in the first place. The UK Government has the power to establish an inquiry covering any part (or the whole) of the UK. It can also establish an inquiry jointly with the devolved administrations, or establish an inquiry on behalf of more than one UK Government Minister.

An inquiry set up by a devolved administration may have more constrained powers. 8 An inquiry established by the UK Government can look into matters which are devolved and use the powers in section 21 to compel evidence and witnesses, provided certain conditions are met. In order for a UK inquiry to include in its terms of reference a matter that was devolved at the time of the event being inquired into, the relevant devolved administration must be consulted. They must also be consulted if the chair is given power to compel the production of evidence.

Points for discussion

The IPPO workstream defines a public inquiry as: (i) a major investigation into a topic of public concern (ii) established on a temporary basis (iii) by a government minister but (iv) enjoying a significant degree of operational independence to (v) provide an account of what happened and the lessons that can be learned from the experience.

This definition excludes parliamentary inquiries and will normally be focused upon statutory inquiries.

Public inquiries exist within a wider accountability ecosystem but there is very little information within the wider literature of:

- how they might coordinate with other accountability actors to share knowledge or insight; or

- how inquiries might be designed differently in order to address a number of well-known concerns.

Section 2: What concerns exist around public inquiry design?

A small but generally descriptive literature exists on the topic of public inquiries. What is striking about this existing body of research is that evidence-based design-led analyses are almost non-existent, and ‘a widespread view exists that the public inquiry is an ineffective means of lesson-learning’. 9

Another highly relevant observation from the literature is that public inquiries tend to be what Perrow described as ‘left censored’, in that they are used to examine failures and fiascos when inquiry-like processes might actually be equally, if not more, important were they focused on lesson-learning from examples of policy success and ‘what works’. 10 Perrow’s point dovetails with the recent emergence of ‘positive public administration’ which is committed to adopting a design-led and lesson-learning approach. 11

The existing body of work on public inquiries does, however, focus attention on a number of perennial concerns which can be summarised under the following headings:

- Executive control

- Operational independence

- Aims and ambitions

- Length and cost

- Skills and knowledge

- Follow-up and good practice

1. Executive control

Ministers decide the form and function of public inquiries. 12 They also decide who will lead the inquiry and the resources that he or she will have at their disposal. The 2005 Inquiries Act has been criticised for removing any formal role for parliament in inquiries. As recently as 2017, the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC) noted: ‘We remain concerned about the lack of mechanisms for meaningful Parliamentary oversight over the establishment of both statutory and non-statutory inquiries.’

It argued that the House of Commons should have a greater say in a range of matters before an inquiry is set up. For example, an ad hoc Select Committee, PACAC suggested, should have the opportunity to report on the Government’s proposed terms of reference for a public inquiry, and to recommend whether the inquiry should be a statutory one.

It also recommended that there should be a vote in the House on an amendable motion before the terms of reference are formally set, and that this motion should also indicate a timescale and budget for an inquiry. Under the 2005 Act, none of this is required and no such parliamentary activity can bind a minister. 13

2. Operational independence

Concerns have also been expressed as to the operational independence of statutory public inquiries – not least as the 2005 Inquiries Act does include provision for: (i) ministers to bring an inquiry to a conclusion before publication of the report (section 14); (ii) ministers to restrict attendance at an inquiry or to restrict disclosure or publication of evidence (section 19); and (iii) for ministers to determine whether sections of the final report should be withheld in the public interest (section 25). 14 In March 2014, the House of Lords Select Committee on the Inquiries Act 2005 published a report that concluded that concerns over ministerial interference had proved unfounded. 15

3. Aims and ambitions

One of the key debates concerning public inquiries revolves around their basic aims and ambitions. According to the Ministry of Justice, the Government considers ‘preventing recurrence’ to be the main or primary purpose of public inquiries. The broader literature, however, suggests that public inquiries may in fact possess a number of potentially incompatible objectives. The 2005 report by the Public Administration Select Committee identified six principal purposes:

- Establishing the facts – providing a full and fair account of what happened, especially in circumstances where the facts are disputed, or the course and causation of events is not clear;

- Learning from events – and so helping to prevent their recurrence by synthesising or distilling lessons which can be used to change practice;

- Catharsis or therapeutic exposure – providing an opportunity for reconciliation and resolution, by bringing protagonists face to face with each other’s perspectives and problems;

- Reassurance – rebuilding public confidence after a major failure by showing that the government is making sure it is fully investigated and dealt with;

- Accountability, blame and retribution – holding people and organisations to account, and sometimes indirectly contributing to the assignation of blame and to mechanisms for retribution;

- Political considerations – serving a wider political agenda for government either in demonstrating that ‘something is being done’ or in providing leverage for change. 16

As several observers have commented, the emphasis that is placed on each of these objectives might lead to a preference for a very different style or form of inquiry process. An emphasis on one objective (e.g. the distribution of blame) might reduce the chances of optimising other objectives (e.g. lesson learning). A focus on detailed fact-finding and a forensic exploration of what happened might also grate against the broader cathartic or therapeutic role of inquiries.

A related but more specific criticism is that public inquiries inevitably get drawn into ‘blame games’ as different individuals and organisations seek to limit the degree to which they can be shamed or scapegoated. This – the existing literature suggests – leads to a defensive approach emerging amongst witnesses which, in turn, militates against an open, mature and future focused discussion about what went wrong and what might be learned. (Hence the common criticism about inquiries actually contributing to an ‘ongoing failure to learn’.) 17

4. Length and cost

A perennial concern is that public inquiries take too long and cost too much. In the UK, the frequency of public inquiries has increased and spending on them was £638.9 million between 1990 and 2017. 18 The length of time inquiries tend to take risks diminishing the impact of an inquiry’s findings, while also increasing the likelihood that responsible ministers or officials will have moved on or retired by the time the final report is published. And yet if an inquiry is to collect all the relevant facts, ensure their accuracy, develop a mature grasp of a complex topic and adopt a person-focused approach that allows victims to give voice to their feelings and frustrations then it is unsurprising that inquiries tend to be long and expensive.

In 2017, the Institute for Government suggested inquiries should produce more interim reports, and it is relevant that the report produced by Meyer et al. in September 2021 suggested that a non-governmental, knowledge broker-led public inquiry should be expected to issue its interim findings within a year and its full report within 18 months. 19

5. Skills and knowledge

Although public inquiries are a fairly consistent and common element of the administrative landscape there are very few support structures to identify ‘best practice’, share ‘what works’ or even to pass on the tacit knowledge about effective inquiry governance that chairs and secretariats inevitably develop.

In 2014, the House of Lords Select Committee on the Inquiries Act 2005 recommended that a new unit should be established within Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service to be responsible for running inquiries. This would both act as a repository of good practice in inquiry administration and would reduce set-up costs incurred by each new inquiry. This unit could also have acted as a ‘centre of excellence’ for thinking about the design and delivery of public inquiries, possibly even drawing on international experience, but the Government rejected these recommendations. (In 2017, the Institute for Government returned to the topic by recommending that a central secretarial unit should be established in the Cabinet Office.)

A related debate concerns ministerial patronage and questions whether senior members of the judiciary actually possess an appropriate skillset.20 Two-thirds of all the inquiries held between 1990-2017 were chaired by a judge, and yet the Inquiry Rules 2006 simply stipulates that the appointee has the ‘necessary experience to undertake the inquiry’. The legislation also allows the minister to appoint a panel to lead an inquiry.

6. Follow-up and good practice

As a process statutory inquiries essentially begin and end with the government minister who establishes them. There is no statutory requirement for the minister to accept an inquiry’s conclusions or recommendations. 21 Once an inquiry has reported, the chair’s involvement normally ends and the secretariat typically disbands, and responsibility for the issue reverts to the department that set the inquiry up. Even when recommendations are accepted there are no formal processes to ensure that they are actually implemented. 22

Of the 68 inquiries [statutory and non-statutory] that have taken place since 1990, the Institute for Government discovered that only six have received a full follow-up by a select committee. The Institute suggested the introduction of a new ‘core task’ for select committees that would require them to follow up on the implementation of inquiry recommendations annually for the five years following an inquiry. 23

The existing knowledge base on public inquiries, with only a few exceptions, is largely descriptive and tends to focus on a well-known set of challenges. To put the same point slightly differently, the existing evidence base is predominantly problem-focused rather than being solution focused with a clear design emphasis. This is reflected in Charles Parker and Sander Dekker’s conclusion about the lesson-learning capacity of public inquiries: ‘when it comes to enacting meaningful reform, the dustbin appears to be the norm’. 24

There is almost no research that seeks to challenge or expand the dominant (narrow) view of how public inquiries operate, through the injection of an evidence-based and innovation-focused account of how inquiry processes might be improved in terms of governance, process, inclusion, outputs or outcomes. What is missing is any purely typological statement of different inquiry approaches – or, put slightly differently, any focus on innovative inquiry design.

Section 3: Innovative inquiry design and inception

The main finding from the analysis of the existing research base is that statutory public inquiries tend to work through a fairly narrow and standardised model which is assumed to be appropriate for almost any issue of ‘major public concern’.

In many ways, the key aim of this IPPO workstream is to question the narrowness of the assumptions sustaining this model, and to draw on an international evidence base in order to demonstrate the existence of innovations and alternatives that can be utilised successfully within the public inquiry model. Before exploring these options through the development of a draft typology it is important to highlight three further issues within the existing scholarship:

- As already noted, although the literature is often critical of public inquiry processes, very few studies offer any practical or evidence-based suggestions for reform.

- The role, development and significance of tacit knowledge within inquiry processes is highlighted as a critical resource but no study has attempted to collect or explore this resource.

- The key challenge for any inquiry process appears to be ensuring that a future-focused emphasis on lesson-learning is not displaced by a focus on blame, retribution and scapegoating.

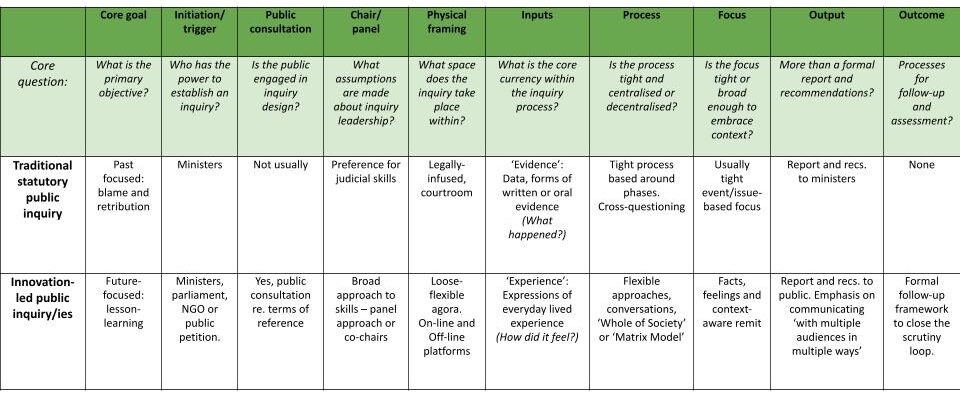

With these shortcomings in mind, Table 1 (see below) attempts to offer a simple model that can be used to stretch the parameters of current thinking about inquiry design and delivery. 25 The aim of Table 1 is to demonstrate the existence of choice and to encourage creativity in inquiry design. The pandemic prompted extraordinary innovation within society, and there is no reason why this dynamic should not be continued into the design and delivery of the public inquiry.

Moreover, the systemic nature of the pandemic arguably demands a more expansive and creative approach to learning if the insights and lessons of the crisis are to be harnessed to building future resilience. To put the same point slightly differently, while public inquiries have in the past tended to focus on a fairly discrete or specific topic, the COVID-19 inquiry will be required to range far more widely in terms of policy areas and societal consequences. The aim of this document (and the wider IPPO workstream) is therefore to place the topic of inquiries within the broader ‘innovation landscape’.

Table 1: The ‘choice architecture’ of public inquiries

It is, however, possible to argue that Table 1 is itself not creative enough due to the manner in which it retains a singular focus. Lesson-learning in the context of COVID-19 arguably needs a more pluralistic – or more precisely, connective – inquiry approach, for at least three reasons:

- We already know there will not be one public inquiry. There will be multiple inquiries operating at different territorial levels which in itself raises distinctive questions about boundary issues, data sharing, witness fatigue and avoiding systemic overload (or what in the literature is described as ‘going MAD’ – i.e. multiple accountabilities disorder).

- We already know that public inquiries will be operating as part of a broader accountability ecosystem within which parliamentary inquiries, for example, have already and will continue to scrutinise decision-making processes and policy responses. The need for public inquiries to complement rather than duplicate other mechanisms is a key design challenge.

- We already know that COVID-19 is a very broad and multidimensional topic of inquiry. A wide variety of affected communities and organisations will want to engage in cathartic or therapeutic forms of giving voice to their experience and feelings. Securing authenticity and legitimacy by connecting and listening to communities will be vital.

These three characteristics underline both the risks of automatically adopting a traditional public inquiry model, and the potential benefits of building-in more creative design-led elements. There are obviously design choices to be made within the traditional public inquiry model – the Scottish Government’s decision to launch a public consultation on the aims and values underpinning its planned COVID inquiry being a case in point.

However, the range of potential design options is actually far broader and might embrace a far higher level of innovation than is commonly recognised. In many ways, the classic statutory public inquiry is a highly centralised and explicitly hierarchical process which, although nominally focused on lesson-learning, is primarily a vehicle for the apportionment of blame.

The distribution of blame

This is a critical point. The distribution of blame (and credit) should arguably be an element of any public inquiry but there are at least two critical perspectives that need to be weighed against this emphasis:

- The first is simply that in terms of societal benefit and future pandemic resilience, a focus on mature and evidence-based lesson-learning is likely to be of a far higher value than a focus on finding who should ‘carry the can’ for failures.

- Secondly, there is a basic issue about public expectations, the limits of accountability, the complexity of modern governance and the novelty of COVID-19. Put very simply, COVID was a new virus that exerted a system-wide risk on modern society that demanded a response by a vast network of organisations and actors.

The traditional inquiry role of finding out who or what was to blame might in itself be a problematic ambition in light of the well-known manner in which complex networks tend to produce ‘fuzzy accountability’. And yet an inquiry process that fails to find a clear focus of failure may in itself be denounced as little more than a whitewash. Pulling the public into the inquiry process, and engaging with concerned communities through creative conversations during the inquiry process itself, might be a valuable way of both building trust and exposing inevitably complexities.

The great weakness, however, of thinking about innovative inquiry design at the planning stage is that it risks overlooking the ongoing issues that will need to be considered, irrespective of specific design components. Initial design decisions can often be ostensible, but the reality of functioning can be very different. This brings us to a focus on innovative inquiry processes and practices.

Section 4: Innovative inquiry processes and practices

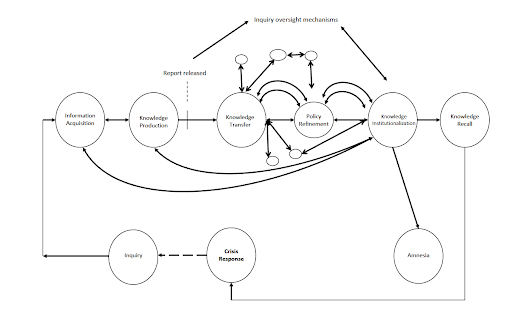

Regardless of initial decision choices, inquiries will still have to follow a generic process reflecting a series of common functions. This process and the associated functions are represented in Diagram 1 (see below).

The purpose of this fourth section is to define those functions and then discuss innovative practices, or aspects of inquiry business that have been proven to produce good outcomes. 26 However, the value of processual thinking generally in relation to inquiries relates to the need to think about complexity, the constellation of actors involved across a learning episode and the need for inquiry actors to think prospectively about future stages before they begin.

Diagram 1. The inquiry process

Information acquisition

Information acquisition relates to the way information is generated (note that this is different to the generation of knowledge). The key innovation here relates to the need to have multiple ‘logics for action’ driving the methods used to generate evidence and the analysis of that information.

The three dominant logics for action that are required for an effective post-crisis inquiry are (i) legal-judicial, (ii) public-managerial, and (iii) technocratic. These need to be synthesised effectively. If an inquiry requires a legal component within it then it will inevitably have to address the tensions that materialise between the legal-judicial logic for action and others, particularly that which is shared by public managers and policy officials. These tensions tend to reflect the differences between pursuing accountability and pursuing policy learning.

However, they are possibly not quite as large as the ‘blame-no-learning hypothesis’ that dominates the existing inquiry literature might suggest. The legal profession and the public managerial profession both bring valuable commodities to the inquiry in terms of policy learning. When inquiries take the forensic construction of evidence from the lawyer and craft it into usable knowledge via the public manager, their lessons become formidable – the implication being that inquiries need to understand and acknowledge their role in relation to the synthesis of different perspectives and world views. There are a number of practical steps that can be easily taken in this regard.

First and foremost, inquiries need chairs and/or panel members with a mix of skills and a capacity to see beyond their own professional logic(s). ‘What is needed are fox-like cognitive styles, i.e. people who have at least some insight from a range of different fields and who can balance conflicting views and evidence rather than those who know a lot about one specific area and have strong world views’ Christoph Meyer and his colleagues argue: ‘It would be helpful for chairs, or co-chairs, to combine expertise in leading a multi-disciplinary team of researchers, dealing with different strongly expressed views and being cognisant of the reception of inquiries in public.’ 27

Secondly, inquiries can benefit from employing specific actors who have the capacity to engage across and connect ‘logics for action’ together. The potential for special advisers to play a fox-like role in terms of ranging across professional domains in order to nurture an appreciation of different forms of knowledge and contrasting perspectives is significant.

Thirdly, inquiries that need to utilise the public hearings should think about innovative ways in which it can be modified or supplemented in order to better facilitate policy learning outcomes. These include:

- using the Accident Investigation Board methodology in order to trade anonymity for candour in evidence taking (SARS Commission);

- using hearings for memorialising purposes (SARS Commission/Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission);

- using coronial-type hearings for forensic reconstructions of fatalities (Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission); and

- using a ‘Hot Tub’ questioning format of witness panels to encourage the co-constitution of evidence (Canterbury Earthquakes Royal Commission).

Involving affected communities and members of the public in the inquiry process could play a key role in ensuring the public’s acceptance of the inquiry’s outcomes and for building public trust in future preparedness efforts. Public engagement can also be viewed as itself a form of lesson-learning.

It is worth noting that providing an arena for public testimony can also have important lesson-learning consequences. The Pennington inquiries, for instance, into E.Coli outbreaks in Scotland (1996) and South Wales (2005), highlighted the critical role of the participation of victims in creating public awareness about food safety. A ‘whole of society’ approach with a more distributed and decentralised structure could seek to co-ordinate and learn from a matrix of linked inquiries (discussed below).

But taking this innovation focus even further, public managerial logics can be harnessed via more typical policy consultation but also atypical processes which include:

- The use of publicised discussion papers and invitations to submit feedback. This need not be through traditional submissions but rather through collaborative forms of stakeholder engagement (The Pitt Inquiry, which travelled to implementing agencies and created co-constitutive workshops around which stakeholders collaborated);

- Typical forms of policy analysis driven by public managers with experience in program evaluation and atypical forms of commissioned research which focus on lived experience and memorialisation (Pitt Inquiry and SARS Commission); and

- Participatory governance mechanisms.

Technocratic logics can be harnessed via the use of innovative processes such as:

- Technical peer-review process through which technical reports are developed, published and discussed to generate public debate amongst experts (Canterbury Earthquakes Royal Commission).

- The replication of large-scale technocratic collaborations which ‘worked’ in the past (Pitt Inquiry and reuse of the Foresight Flood Management network).

- The innovative use of scientific/engineering/health panels as a means of generating questions, analysing information and writing/editing reports (Pitt Inquiry).

Knowledge production and knowledge transfer

Knowledge production and knowledge transfer (see Diagram 1, above) need to be connected in a way that acknowledges both the crafting of information into recommendations and the art of persuasive report writing. In this stage, it is absolutely essential that those who write reports think prospectively about the following stages in the process: knowledge transfer, policy refinement and knowledge institutionalisation.

- Transfer involves recommendations pinballing around public sectors and getting accepted, rejected, lost and rediscovered in a very messy process. Crucially, actors in this process often have no obligation to implement so great expectations in the inquiry room are often dashed as they re-enter the governmental process.

- Policy refinement often involves official-led mini-inquiries after the main inquiry and are often used to strategically reinterpret or kill off politically thorny or ‘big ticket’ recommendations.

- Knowledge institutionalisation represents the stage beyond implementation when recommendations get hardwired into systems in ways which keep them alive until the next crisis. Note the messy nature of Diagram 1 across these stages – this is intentional. There are lots of actors, feedback loops, iteration and complexity here but this is rarely considered by inquiries or indeed inquiry scholars. (It is in regard to post-inquiry complexity and off-stage negotiations that interviews with former inquiry chairs might reveal significant insight.)

The innovative inquiry will think about these challenges prospectively and craft reports accordingly. Here, we can echo Dominic Elliott’s original prescription about knowledge transfer and inquiries, which was that change management specialists should be allowed to play a role in the drafting of reports so that transfer can occur smoothly. 28

However, we might suggest instead that experienced public servants with a strong public-managerial logic for action perform this role. That logic is crucial to policy learning, precisely because it equips agents inside inquiries with knowledge about what will happen to their lessons when they are published. Thus, we can advocate that it is absolutely essential that inquiries contain seasoned public administrators who have experience of the policy implementation process and that they are allowed to influence the crafting of reports and recommendations. 29 This is what makes recommendations ‘implementable’.

The extent to which they perform this role will obviously fluctuate depending on context but inquiry architects need to recognise that the public-managerial logic for action is the only rationality that is regularly shared between those who create and those who implement lessons. The language of policy implementation therefore needs to be spoken inside inquiries, so that recommendations have the capacity to travel.

A simple comparison can be used to reinforce this point. Compare the public managerial pages of the Pitt Inquiry in the United Kingdom with the Royal Commission on the Building and Construction Industry in Australia. 30 The Pitt Inquiry was written by public managers for public managers and was almost entirely implemented. This is because (in part) it included implementation blueprints and costings for implementation, which closed off early excuses to reject.

The Building and Construction Industry inquiry, by contrast, contained 212 recommendations, 243 sub-recommendations and 23 volumes of report which were described as impenetrable by implementing actors. Only 80 recommendations (38%) were implemented. Other inquiries have used other means to develop legitimacy through their writing. The SARS Commission, for example, employed a journalist to edit the reports so they would appeal to a public audience.

The main insight emerging from an innovative inquiry processes and practices perspective is the need to think about the lesson-learning dimensions of public inquiries beyond the initial design and delivery, in order to maximise the chances of positive policy learning.

As Alastair Stark’s research has revealed in great detail, it is the post-inquiry phase that creates the most potential for ‘learning loss’. 31 More specifically, although it is rare for ministers to seek to publicly reject the findings and recommendation of a public inquiry, it is not uncommon for them to triage recommendations or to transfer responsibility for their implementation to arm’s-length agencies who have little incentive to act on them.

One tool for inquiries to mitigate this risk of learning loss is to ensure that recommendations are drafted in ways which create (or allocate) reform ‘champions’ to them. Without custodians of this nature, recommendations can wither easily. Not only can ‘champions’ or nominated reform advocates lead on the overseeing of implementation processes but they can also play a critical role in relation to promoting and sustaining the need for reform on the political agenda and within the policy transfer environment.

The critical point that this fourth section is trying to underline is that innovative inquiries do not just recommend, they plan and prepare implementation channels and actors for this uncertain and potentially hostile period in a learning episode.

Policy refinement

This introduces the topic of policy refinement, as set out in Diagram 1. What might be termed ‘policy refiners’ are the quasi-independent policy analysis mechanisms that are convened for the purposes of further exploring recommendations. In complex policy areas, refiners are essential because inquiries often set a broad direction of travel or a policy outcome without necessarily engaging with the detail of how to get there. Refiners are therefore required to map out potential implementation routes and uncover the costs and benefits of different options.

However, the clarification and the treatment of lessons learned (i.e. the post-inquiry ‘policy refinement’ stage) can change an inquiry’s recommendations significantly. Examples here include: the Capacity Review Committee and the Agency Implementation Task Force convened after the SARS Commission; and the Victorian Bushfires Powerline Taskforce and the ‘Learning from Failure’ exercise after the HiP Royal Commission in Australia. All of these ‘inquiries after the inquiry’ reinterpreted the main inquiry’s recommendations in significant ways – the main implication being that the stronger an inquiry’s recommendations are in terms of detailed policy prescription and implementation blueprints, the less space there will be in the ‘policy refinement’ stage to disrupt or derail those recommendations.

Knowledge institutionalisation, amnesia and recall

This brings the discussion to a focus on knowledge institutionalisation, amnesia and recall. The existence of an evidence-based, lesson-learning approach is in itself unlikely to ensure that future resilience is bolstered or organisational effectiveness increased. A very large academic literature exists on the theme of institutional amnesia: policy challenges tend to reoccur in an almost cyclical process without clear evidence of learning from the last occurrence. The explanation for this might be political (i.e. the responsible minister rejected lesson-learning opportunities for short-term or partisan gain) or administrative (i.e. the reform agenda was not implemented by the teachers, social workers, local government officials, etc. at the end of the bureaucratic chain of delegation).

This is a crucial point. Non-implementation of public inquiry recommendations is often found to be related to the role and non-compliance of street-level bureaucrats rather than to any more higher-level subterfuge. In the absence of legislative mandates or close supervision, it is too easy for street-level agencies and actors to ignore recommendations, especially when already faced with complex and often incompatible demands. And yet inquiries tend to assume the incentives that apply to central government will trickle down to ensure effective compliance by local actors.

This underlines a point that has already been made several times: innovative inquiry processes provide a way of co-producing and co-designing not only knowledge and insight but also more effective policy responses. By working with those communities that have been affected by the challenge, but also by those professional communities who will be expected to implement new policies or ways of working, it is possible to align interests and smooth implementation processes. 32

Another way of strengthening institutional memory is for inquiries to proactively seek to embed a future scrutiny process so they cannot be easily forgotten. The Victoria Bushfires Royal Commission and the Pitt Inquiry both provide best practice examples of how this can be done. Neither inquiry simply faded away once their reports were published. Instead, they proposed recommendations through which their reform agenda was audited and government was held to account for their leadership of the implementation process. These recommendations, of which the creation of an Independent Implementation Monitor was the most innovative, were primarily orientated towards ensuring their lessons were hardwired into government in the first instance.

One clear prescription is that inquiries should recommend the means of oversight through which the implementation of their reforms can be audited for the long term. In the UK, for example, this might involve connecting a public inquiry with the review capacity of the National Audit Office. A slightly more creative way of ensuring that an inquiry’s recommendations are not forgotten involves making memorialising recommendations via tools such as disaster education in schools, specific commemoration events, and publicly held and acknowledged archives – the aim being to ensure that governmental and bureaucratic ‘churn’ does not erode institutional memory so that lessons are quickly forgotten.

Section 5: What next?

The COVID-19 crisis has undoubtedly been complex. An inquiry process will inevitably have to expose and tease apart numerous and often conflicting narratives (from ‘the experts’, ‘the politicians’, ‘the officials’, ‘the public(s)’, etc.) and all in a context of uncertainty.

A more distributed, decentralised and deliberative inquiry model could create space for these different stakeholders to not only give voice to their thoughts, views and opinions but also to listen to the perspectives of others. A matrix of inquiries could adopt a hub-and-spoke model whereby a programme of different inquiries explore the impact and response to COVID in different contexts and through a variety of methods. 33

Another benefit of adopting a more variated model might be that it places the responsibility for thinking about the lessons that can and need to be learned back on to those communities that are arguably best placed to identify them (i.e. teachers in schools, doctors in hospitals, etc.). The design challenge could therefore be seen as extending far beyond the effective planning of a single (national, top-down, bureaucratic, facts-based, legalistic, etc.) inquiry process into considering the proportionality, focus and method of a range of inquiries.

The risk is that the complexity and costs of such a network of scrutiny structures might, without careful management, become unwieldy and burdensome; the benefit, however, would be a form of inquiry framework that is deeper, richer and more inclusive than anything ever tried before in the wake of an issue of major public concern.

Once again, it would be the connective capacity between the various parts of the creative inquiry processes that would be critical, in order to make sure that the total value was far more than the sum of the parts.

The point is simply one of injecting creative thinking and evidence-based challenge into the design and delivery conversations that are currently taking place within and beyond the UK. The concern is that traditional inquiry models are unlikely to encourage a broader or more creative view that might lead to more effective responses to future challenges.

Levels and politics

One way of wrapping up the discussion that this document has hopefully provoked is through a very brief focus on levels and politics. Thinking in terms of levels is simply a way of distinguishing between degrees of change which might be set out as follows:

- Level 1: This is the status quo. Do nothing. Operationalise the standard public inquiry format despite the high likelihood of sub-optimal outputs and outcomes.

- Level 2: Inject creative design-thinking into the standard statutory inquiry model by engaging with at least some of the dimensions outlined in Table 1.

- Level 3: A more innovative and radical option based around the notion of a matrix or ‘whole of society’ approach which is likely to produce a richer and more integrated set of insights.

While this focus on different levels of reform, from ‘do nothing’ to ‘radical think’ – with the option of blending ‘continuity and change’ as a mid-range option – provides a useful framework, it is necessary to acknowledge what might be termed the politics of public inquiries.

For ministers and senior officials, accountability mechanisms are likely to trigger an immediate defensive reaction due to the highly immature and adversarial nature of British politics. The tightly controlled top-down quasi-independent nature of the traditional statutory inquiry is therefore already the product of an implicit constitutional design process.

The simple point is this: recommending the redesign of traditional inquiry processes represents a highly political request, in the sense that the measures being advocated tend to inevitably involve ministers ceding some level of control. Providing evidence of where design innovations in inquiry processes have ‘worked’, in the sense of cultivating an emphasis on sensible lesson-learning and pulling the discussion away from simplistic blame allocation, is therefore likely to be of significant value.

Appendix A: Active and announced 2005 Act public inquiries

Note: a Scottish Coronavirus inquiry was announced in September 2021 but the chair has not yet been appointed.

Source: Graeme Cowie. 2021. Statutory Commissions of Inquiry, House of Commons Library, No.SN06410

Appendix B: Former 2005 Act public inquiries

Source: Graeme Cowie. 2021. Statutory Commissions of Inquiry, House of Commons Library, No.SN06410

References

1 In 2010 the Cabinet Secretary issued a guidance note on the establishment of judicial inquiries which noted the common characteristics of the events that had led to previous inquiries as: large scale loss of life; serious health and safety issues; failure in regulation; and other events of serious concern. See this link.

2 There is always the option to turn a non-statutory inquiry into a statutory inquiry under the 2005 legislation (via section 15). The Child Sexual Abuse inquiry and the Bernard Lodge inquiry both began as non-statutory inquiries. The inquiries into the deaths of Billy Wright and Robert Hamill were converted into statutory inquiries under the 2005 Act after originally being established under different powers.

3 Other options include an independent review; a parliamentary inquiry; an investigation with a public hearings element overseen by a judge or QC; an independent review with a public hearings element; or, in a very limited number of cases, an inquiry established under other legislation, such as the Financial Services Act 2012 or the Merchant Shipping Act 1995. See 4 HL Deb 19 March 2015 [Inquiries Act 2005 (Select Committee Report)] c1174.

4 The Scottish Parliament has issued separate rules under the Act, the Inquiries (Scotland) Rules 2007.

5 Carnegie Corporation of New York, ‘Preventing Deadly Conflict: Final Report,’ (1997); London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, ‘Independent Panel of Global Experts Calls for Critical Reforms to Prevent Future Pandemics’ (link).

6 National Audit Office, ‘Investigation into Government-Funded Inquiries,’ (2018), 17.

7 See Meyer, C. et al. 2021. Learning the Right Lessons for the Next Pandemic, London: King’s College (link).

8 For instance, the Penrose Inquiry (2008-15) could not compel witnesses outside of Scotland to attend.

9 Stark. A. 2019. ‘Policy Learning and the Public Inquiry’, Policy Sciences, 52, p.397.

10 See Perrow, C. 1999. Normal Accidents, New York: Basic Books.

11 Scott Douglas, Thomas Schillemans, Paul t’Hart, Chris Ansell, Lotte Bøgh Andersen, Matthew Flinders, Brian Head, Donald Moynihan, Tina Nabatchi, Janine O’Flynn, B. Guy Peters, Jos Raadschelders, Alessandro Sancino, Eva Sørensen & Jacob Torfing (2021) ‘Rising to Ostrom’s challenge: an invitation to walk on the bright side of public governance and public service’, Policy Design and Practice, DOI: 10.1080/25741292.2021.1972517.

12 The decision to hold or not to hold an inquiry has been subject to judicial review. The 2014 Lords Committee report provides examples of cases where Ministers gave detailed reasons for not establishing an inquiry. See House of Lords Select Committee on the Inquiries Act, The Inquiries Act 2005: post-legislative scrutiny, HL 143, 11 March 2014, p. 35. A subsequent addition to this list was the decision not to hold a public inquiry into events at Orgreave during the miners’ strike in 1984: see HCWS227, 31 October 2016.

13 Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Lessons still to be learned from the Chilcot Inquiry, HC 656, 16 March 2017, p. 14.

14 See Joint Committee on Human Rights, Fourth report session 2004-05, HC 224, 12 January 2005.

15 House of Lords Select Committee on the Inquiries Act, The Inquiries Act 2005: post-legislative scrutiny, HL 143, 11 March 2014.

16 Public Administration Select Committee, Government by Inquiry, HC 51-1, 3 February 2005, pp. 9-10.

17 This is why Christoph Meyer and his colleagues have called for the sequencing of two parallel inquiry processes. The first would focus on lesson-learning and would be led by a non-governmental organisation, the second would be a fact-finding and accountability focused inquiry constituted under the 2005 Inquiries Act. See Meyer, C. et al. 2021. Learning the Right Lessons for the Next Pandemic, London: King’s College.

18 Norris and Shepheard, How Public Inquiries Can Lead to Change, 3.

19 Emma Norris and Marcus Shepheard, How public inquiries can lead to change, Institute for Government, 12 December 2017, p. 9 https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/Public%20Inquiries%20%28final%29.pdf.

20 A discussion of the merits of a judge chairing an inquiry can be found in Public Administration Select Committee, Government by Inquiry, HC 51-1, 3 February 2005, pp. 19-26.

21 In 2014 the House of Lords recommended that those responsible for interpreting and subsequently implementing inquiry recommendations should be placed under a statutory duty to say within a specified time whether they accept the inquiry’s recommendations and, if so, what plans they have for implementing them; and to publish their policy refinement plans or response within three months after the publication of the inquiry report. See House of Lords Select Committee on the Inquiries Act 2005, ‘The Inquiries Act 2005: Post-Legislative Scrutiny. Report of Session 2013-14,’ 85.

22 See National Audit Office, ‘Investigation into Government-Funded Inquiries,’ 31.

23 Emma Norris and Marcus Shepheard, How public inquiries can lead to change, Institute for Government, 12 December 2017, p. 26.

24 Charles F. Parker and Sander Dekker, ‘September 11 and Post-Crisis Investigation: Exploring the Role and Impact of the 9/11 Commission,’ in Governing after Crisis, ed. Arjen Boin, Allan McConnell, and Paul t’Hart (2008), p.255.

25 One issue here is whether these options are compatible with the Inquiries Act 2005 or the Inquiry Rules 2006.

26 More information is provided in: Stark, Alastair (2019). Explaining institutional amnesia in government. Governance, 32 (1), 143-158; Stark, Alastair and Yates, Sophie (2021). Public inquiries as procedural policy tools. Policy and Society, 1-17.

27 Meyer ibid p.14.

28 See Elliott, Dominic. (2009). ‘The failure of organizational learning from crisis—A matter of life and death?’ Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 17(3), 157–168.

29 Meyer et al (2021, 16) notes ‘To ensure that the policy recommendations of the inquiry are actually considered helpful by frontline workers, the inquiry should include practitioners, scientific communities, frontline workers (in this case, doctors, nurses, those working in acquisition, administrators and managers of public health services) and non-partisan policy implementation actors during the knowledge production process, which could contribute to implementation success.’

30 Following the widespread and serious flooding in England during June and July 2007, Sir Michael Pitt conducted an independent review of the way the events were managed. Sir Michael published the interim conclusions of the Review in December 2007: the final report – The Pitt Review: Lessons learned from the 2007 floods – was published in June 2008. The Royal Commission into the Building and Construction Industry, or informally the Cole Royal Commission, was a Royal Commission established by the Australian government to inquire into and report upon alleged misconduct in the building and construction industry in Australia. The establishment of the Commission followed various unsuccessful attempts by the Federal Government to impose greater regulation upon the conduct of industrial relations in that industry. The Royal Commission commenced on 29 August 2001 and was overseen by a sole Royal Commissioner, The Honourable Justice Terence Cole RFD QC. Justice Cole handed the commission’s final report to the Governor-General on 24 February 2003; and the report was tabled in parliament on 26 and 27 March 2003.

31 See for example, Stark, A (2018). Public inquiries, policy learning, and the threat of future crises. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; Stark, A (2019). Explaining institutional amnesia in government. Governance, 32 (1), 143-158; Stark, Alastair (2020). Left on the shelf: Explaining the failure of public inquiry recommendations. Public Administration, 98 (3): 609-624.

32 Meyer op cit. 2021, p. 23. ‘Equally important is the practical feasibility: Do front-line workers consider the recommendation actually helpful? To ensure such a policy fit, the inquiry should include practitioners, scientific communities, frontline workers (in this case, doctors, nurses, those working in acquisition, administrators and managers of public health services) and non-partisan policy implementation actors during the knowledge- production process, which could contribute to implementation success.

33 See Mulgan, Geoff. ‘Contemplating the COVID crisis: what kind of inquiry do we need to learn the right lessons?’ IPPO blog, 15 September 2021.