Policy Responses to Economic Inactivity: Addressing a Cross-Cutting Problem

Rob Richardson, Sarah Weakley, Ka Ka Katie Tsang

Stubbornly high economic inactivity levels are a key contributor to the UK’s challenging economic outlook. IPPO teams at Queen’s University Belfast and the University of Glasgow have been gathering evidence on policy responses to economic inactivity, to improve understanding of how this complex policy problem is best addressed. Here we detail what we’ve learned and the resources we’ve developed in our work this autumn.

Economic inactivity in the UK

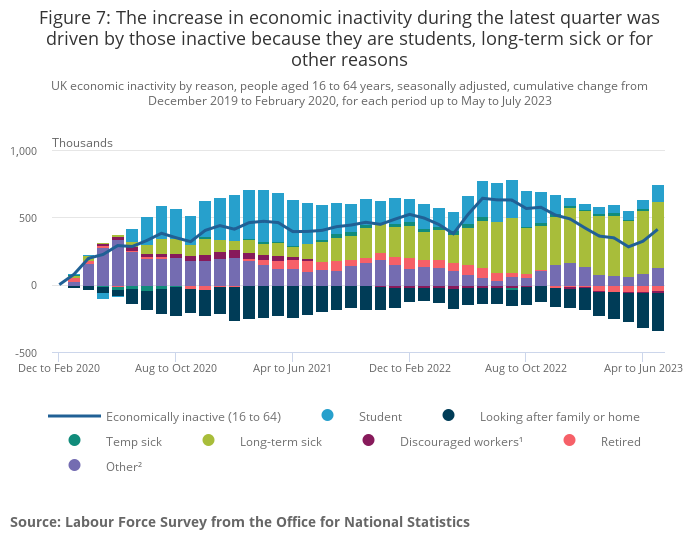

410,000 more people were economically inactive in May-July 2023 compared with December-February 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic1. People can be economically inactive for a number of reasons, including temporary or long-term sickness, retirement, looking after family or the home, and being a full-time student (Figure 1). As Figure 1 shows, the majority of the post-pandemic increase in economic inactivity is due to long-term sickness. This is not necessarily due to economically active people moving straight into inactivity for health reasons. Analysis using longitudinal Labour Force Survey data reveals two separate issues: rising levels of sickness among the older non-working population; and an increase in movements from employment into inactivity for non-health related reasons, particularly retirement.

Trends in long-term sickness and disability are particularly striking, however. 490,000 more people were inactive due to long-term sickness in May-July 2023 compared with December-February 2020. 2.6 million are now inactive due to long-term sickness, which is 30% of the UK’s overall number of economically inactive people. The number of new monthly disability claimants is also double pre-pandemic levels at approximately 30,000 new claimants per month, with particular increases occurring among peopled aged 16-24, and those over 50.

Policy responses to economic inactivity

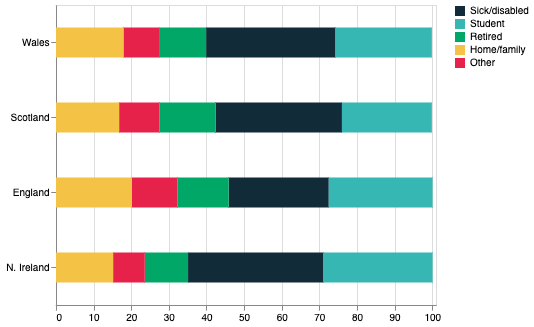

Regional variation in the causes, impacts, and available policy levers mean that ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions to economic inactivity, such as tax relief on pensions, will not work on their own. Northern Ireland and Scotland have consistently experienced particularly high levels of long-term sickness and disability, for example (figure 2), which demands locally-responsive policy solutions.

Source: Devlin (2022), using ONS data. How has Covid-19 affected economic inactivity in Northern Ireland? – Economics Observatory

IPPO has been gathering evidence from across the UK and beyond on policy responses to economic inactivity. IPPO researchers in Northern Ireland and Scotland have respectively focused on two particular issues: economic inactivity among the over 50s, and economic inactivity related to poor health.

For each issue, a policy review was carried out, alongside a roundtable discussion with policymakers and representatives from the public, private and third sectors with experience of interventions to address economic inactivity.

Economic inactivity among the over 50s

IPPO Northern Ireland’s roundtable discussed policy solutions to economic inactivity faced by people aged 50 and over.

Presenters shared learnings from interventions across the UK, and internationally. First, Prof. Graeme Roy, from the University of Glasgow, gave an overview of current trends in economic inactivity and highlighted its distinctive spatial distribution in Northern Ireland.

Dr Anne Devlin, Research Fellow at the Economic and Social Research Institute, then presented data on economic inactivity in Northern Ireland compared with the Republic of Ireland. Divergence in the causes of economic inactivity between the nations reflects how barriers to labour market participation – such as caring responsibilities, employment opportunities, and health – manifest differently in each.

Next, Natalie Anderson, the Age at Work Programme Manager with Business in the Community, outlined the programme’s employability and skills workshops with people over the age of 50. The programme has carried out 1750 Mid-Career Reviews, supported over 500 participants through its Still Ready for Work initiative, and conducted 200 Age Inclusive Business Audits.

Massimiliano Mascherini, Head of Social Policies Unit at EU Agency Eurofound, then presented research on measures taken by EU member states to support older people to be economically active. This highlighted the need to focus on people who wished to work more hours, but also the requirement for policy responses to consider structural factors including the cost of living and economic insecurity.

Finally, Kari Osterud, Director of the Centre for Senior Policy in Norway, presented the centre’s research on supporting older workers. This found several key influences on retirement behaviour in Norway, including being valued by employers, opportunities for lifelong learning, a good working environment, and autonomy and flexibility.

The roundtable overall highlighted the importance of lifelong education and development for retaining older workers, as part of wider multi-dimensional policy responses which include important roles for health and education.

IPPO Northern Ireland’s policy review agreed with these key ideas. It also identified how the decision to retire or leave work is a personal one, but that policies supporting flexible work arrangements, age-friendly workplaces, and opportunities for skills development, can help facilitate the continued participation of older people in the labour market.

Economic activity and poor health

IPPO Scotland’s roundtable considered whether economic inactivity should be viewed as a public health problem rather than a labour market problem. Accordingly, it considered how policy interventions can respond to these cross-cutting challenges.

Prof. Graeme Roy and Dr Rob Richardson from the University of Glasgow firstly highlighted local variation in both the data and policy responses to economic inactivity and poor health. Dr Anne Devlin, Research Fellow at the Economic and Social Research Institute, then spoke about the need for specific policy responses in Northern Ireland which respond to the long-term impact of conflict.

Nic Werran, Partnerships Director at Breaking Barriers Innovations, next presented on the Clacton Place programme. This programme aims to address longstanding health inequalities and high levels of economic inactivity in the coastal community of Clacton-on-Sea in Essex, through a diverse partnership which includes NHS England, Essex County Council, the UK Government’s Department for Work and Pensions, and the voluntary sector.

The Work and Skills Lead at Manchester City Council, Dave Berry, then reflected on Greater Manchester’s distinctive challenges. ‘Working Well’ and ‘Making Manchester Fairer’ actively target the relationship between health and employment and tackle the barriers facing those who are inactive, particularly in the most affected neighbourhoods. By integrating with the wider support ecosystem in Greater Manchester including voluntary and community organisations, Working Well has supported over 25,000 out of 70,000 participants to find employment (as of July 2023), many of whom were deemed unlikely to move into work without specialist intervention.

Finally, Dr Jakov Jandric, Lecturer in Organisational Behaviour at the University of Edinburgh, presented insights from ‘Supporting Healthy Ageing at Work’ (SHAW), a study aiming to co-design workplace interventions to support the health and wellbeing of older workers with employers in the private and public sectors.

The presentations demonstrated the importance of the relationship between health and employment as a focus for policy intervention. Many also reflected on the need to respond to local context, which aligns with the emergence of place-based responses to economic inactivity identified by IPPO Scotland’s policy review.

What next?

The UK’s economic inactivity rates show little sign of reducing. With predictions for a difficult winter ahead in public health terms, the resulting policy challenges are unlikely to subside.

Our ability to understand them is also compromised by issues with labour market data. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has reported increased uncertainty around Labour Force Survey estimates, given falling response rates, which means the estimates should be treated with caution. Growing divergence between Labour Force Survey data on employment and similar tax and workforce jobs data is particularly worrisome for researchers and policymakers.

Governments across the UK are taking a growing interest in addressing economic inactivity and are responding differently. The Scottish Government, for example, is moving to a position where all Scotland’s employment support is provided through the No One Left Behind initiative, which will be administered by local authorities. Whether the UK Government’s DWP follows suit in supporting more localised responses will be worth watching.

Ongoing evaluation of emerging responses and their impact will be crucial in understanding how the challenges associated with economic inactivity can best be addressed. IPPO will continue to monitor developments in policy responses across the UK.

An initial IPPO blog to introduce this work package can be read here, and the other outputs from this work can be accessed as follows:

Roundtable on economic inactivity among the over 50s

Policy review on economic inactivity among the over 50s

Roundtable on economic inactivity and poor health

Policy review on economic inactivity and poor health

- Data derives from the Labour Force Survey, which the Office for Statistics warns is subject to increased uncertainty due to falling response rates ↩︎