Online education for schoolchildren during COVID-19: a scan of policies and initiatives around the world

At least 90% of countries, regions and territories closed all levels of schooling at some point as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This summary, compiled by the International Network for Government Scientific Advice and the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, details which policies each country enacted to support children’s learning during these closures

Case study: Indonesia’s internet quota subsidies to encourage distance learning

Introduction

Education is seen globally as an important driver of everything from social mobility and diversity to economic growth and gender equality.

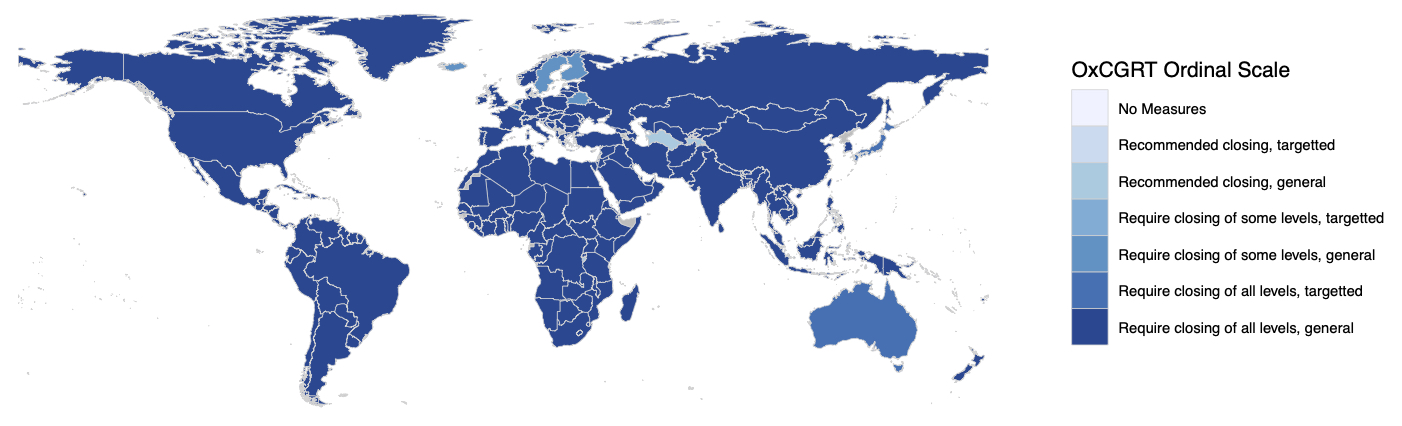

At various times throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, national governments around the world closed schools. The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) database reports that at least 90% of countries, regions and territories closed all levels of schooling at some point during the period January 2020 to March 2021 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, as seen in Figure 1 (see below). UNESCO estimates that the education of 1.5 billion students has been adversely impacted by COVID-19.

Figure 1: Map showing the strength of policies for school closures, highlighting the need for online schooling alternatives

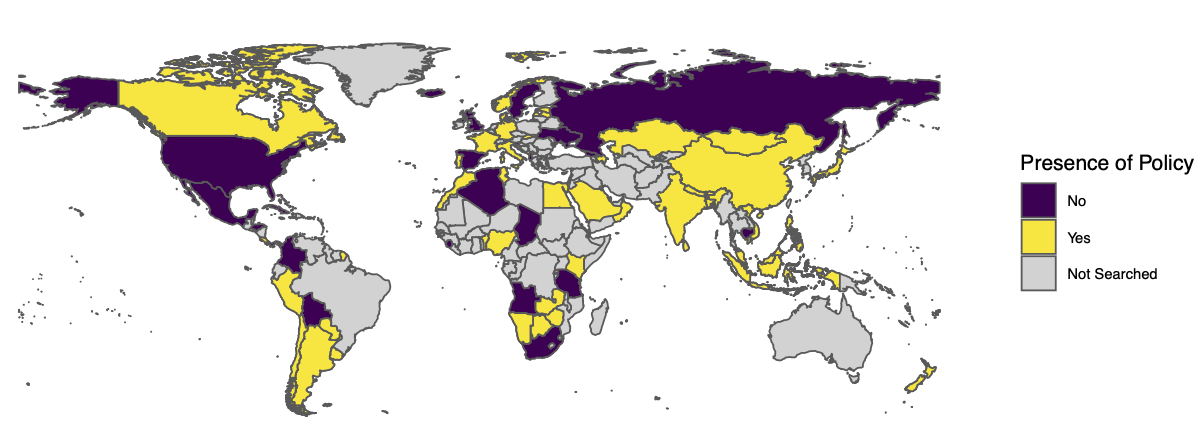

In order to prevent the widespread permanent consequences of loss of education caused by school closures, national governments have introduced different policies to teach children online. This research scan includes information collected by contributors to both the OxCGRT and International Network for Government Scientific Advice (INGSA) research groups. A total of 87 countries were surveyed across all regions of the world. From these, 62 countries were found to have online education policies. For 25 countries no relevant policies in this area were found in the scan, as shown in Figure 2 (see below).

Online education strategies were found to have five key themes: the development of online learning platforms, ensuring a good internet connection, increasing access to internet capable devices, teacher training, and solving non-infrastructure impediments to learning. Two of these themes – investing in internet infrastructure and internet-capable devices – are about enhancing personal connectivity and taking steps to lessen the digital divide.

Figure 2: Map showing the countries scanned by the OxCGRT and INGSA contributors

Throughout the period covered by this scan (1 March 2020 to 1 April 2021), most countries have implemented a combination of policies which are alike in many aspects. Brief country summaries of policies implemented can be found in Table 1 at the end of this scan.

Summary of themes

School closures were most often found to lead to increased development of online learning platforms. 68% of the countries scanned for this report enhanced or built new online learning platforms in order to cope with the extra-capacity required for teaching their school populations online. While the enhancements often meant expanding existing platforms, many countries chose to build new ones from scratch.

These platforms almost always included pre-recorded videos of core curriculum concepts, online lessons, worksheets, and key texts. Some also included live-streaming capabilities for classes, and used interactive elements such as daily quizzes. Developing countries often used third-party platforms such as Facebook Live and YouTube. Globally, these platforms were accompanied by free access to online productivity applications (like Microsoft Office, or the paid version of Google’s productivity suite).

Internet access is a major barrier for online schooling. In order to overcome this, many countries have provided additional assistance to increase internet access. Free or low-cost provision of internet access has been targeted at students, families, and teachers to aid online education uptake. In some countries this additional assistance for internet provision has been targeted at low-income families. Policies aimed at improving broadband access were also common, and characterised by additional investments in mobile cell towers and physical cabled connections to households. Finally, zero-ratings policies – where users are not charged for accessing specific online content – were used in a number of countries for educational websites and platforms.

In many countries, devices – in the form of laptops or tablets – have also been provided to students and teachers through ad hoc schemes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Within these policies, devices have either been given as a loan or outright, with device provision sometimes targeted at lower-income households. Some countries have provided subsidies or financing to families to buy their own devices, again often targeted at low-income households. Several countries have also provided free routers to low-income families.

Countries also developed policies to overcome the non-infrastructure barriers to learning. This policy was based around new online education guidelines for teachers and schools on how to develop lessons and prevent harm to students online. For unclear areas within these guidelines, FAQs, social media information, and phone/video hotlines have also been set up in some countries. These deal with everything from new teaching techniques and teaching students with disabilities, to technical support.

The training of teachers has also occured online, seeking to aid the switch to digital teaching and content provision for their students. Teacher training focused on how to better teach children online, and to improve internet and IT literacy. Countries have also developed teacher-targeted online platforms which aid teaching and monitor obstacles to childrens’ learning.

Novel policies

While many policies are common across countries, some unique policies have been found:

In Azerbaijan, in addition to online schooling the government provided various online extracurricular activities for school children. These included online chess tournaments, online arts competitions (painting, singing, playing musical instruments), as well as a ‘Scientist for a day’ competition in cooperation with NASA.

In the Cayman Islands, the government established partnerships to provide COVID-19 counselling support for students and staff.

As well as providing new devices for some students, India has also provided braille tactile readers for visually impaired learners.

By mid-April 2020, Luxembourg’s government had implemented an “extraordinary” family leave program to free up parents for their new level of involvement. The law stipulates that a parent can take leave if they have a child at home that is required to learn from home and is below the age of 13; or if the child is ordered to stay at home via a quarantine order; or if the child is “vulnerable” to COVID-19 infection (and hence stays away from school even if schools are open). Various government departments also launched online platforms for extracurricular activities including online fitness activities, challenges & exercises for children and their parents (Ministry of Sports; Ministry of Education, Children & Youth; National Youth Service; & ENEPS).

In New Zealand, the government connected ‘Learning Support Coordinators’ with families remotely. The role of these coordinators is to identify the needs of students and develop action plans to provide them with support services if required.

In Rwanda, SMS services are used to communicate important messages and reminders for parents on learning schedules of children. Children with disabilities are provided access with digital formats of communication such as translating the REB scripts into Braille, close-caption and Sign Language. Teachers are supported through mobile credit to be able to call to the most vulnerable students and provide remote support and tutoring.

In Slovakia, the Ministry of Investments, Regional Development and Informatisation, Single Digital Gateway portal (slovensko.sk) is continuously updating a list of companies which have decided to provide assistance in the form of preferential or free provision of technologies, solutions, and virtual education for schools and students.

In Vietnam, the Education Ministry offers free server rentals for distance learning for universities and schools.

Online education platforms and online content delivery for students

In Argentina, the National Ministry of Education released a free digital program for virtual classes and teaching material for students, teachers, and families. The Seguimos Educando platform, developed by The National Ministry of Education, provides teachers, students and families with free lessons, instructions, and learning materials for all grade levels through online resources (in addition to other media).

In the Bahamas, the Ministry of Education provided live and recorded lessons online with associated activities, with 30% uptake of the online lessons.

In Benin, online content was provided via a platform to the majority of students and SMS messaging platforms were used to disseminate education where other mediums would not be possible. A US$70,000 Global Partnership Education grant from the World Bank was provided to develop online learning content and build online capacity.

During school closures in Bhutan, content was broadcast on YouTube and Google Classroom, in collaboration with local private companies who provided the broadcasting equipment and assisted with content and Google who provided the software. For younger children, lessons were only offered in Mathematics, English, and Dzongkha. For classes seven to 12, the lessons are theme-based and based on the entire syllabus.

In Botswana, the government partnered with local cell phone providers to offer free service to access educational contents.

In Chile, The Ministry of Education created an online learning, teaching, and training platform for teachers, students, and families participating in distance learning. The Aprendo en Línea program released by the Ministry of Education in Chile provides children and their families with online learning tools and curricula for all grade levels and all learning subjects. The platform also provides extensive resources and training videos for teachers to support their transition to online teaching.

In China, the Ministry of Education, together with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), launched an online portal for primary and secondary school students in February 2020. The platform provides digital materials for schools to conduct teaching online and is capable of supporting 50 million students using it simultaneously. As of May 2020, the platform had been visited over 2 billion times by people from all 31 mainland provinces. However, students and institutions have raised issues (such as technical limitations), especially in rural areas which may lack reliable internet connectivity and where many students/families are unable to afford the necessary equipment to access online content.

Costa Rica set up a centralised website for educational resources for teachers and students. More than 1 million students were provided with an institutional email, although only 590,000 activated it to use the educational platform. Only about 60% of students have access to the educational platform, while the rest use Whatsapp and offline resources. Only 34% have the equipment and connectivity needed to fully participate, with 35% of students’ homes not having an internet connection at all.

In the Czech Republic, the government set up a website which contains links to online educational tools, updated information and examples of good practices, as well as experiences regarding distance education.

In Denmark, both Office 365/Teams and Google G Suite for Education/Hangout Meet were made available free of charge to all schools.

In Egypt, the Ministry of Education and Technical Education (MOETE) provided educational content by grade level and subject to support digital learning for all students, parents, and teachers through the Educational Knowledge Bank (EKB). The EKB features videos, images and documentary films to help explain the various lessons, and numerous books.

In England, under the Get Help With Technology programme, government-funded support is available for schools/colleges to get set up on one of two free-to-use digital education platforms: G Suite for Education (Google Classroom) or Office 365 Education (Microsoft Teams).

Fiji and Vanuatu provided online education via websites and a Moodle platform for all ages.

In France, the National Center for Distance Education (CNED) introduced the online platform Ma classe à la maison (My class at home) with online content for primary, lower secondary and upper secondary students. In addition to stock lessons, there are tasks to complete and lessons given by video-conference.

Schools in Hong Kong adopted various e-learning strategies and provided learning materials to students through e-learning platforms and existing learning management systems, emails, and school websites.

In India, the pre-existing multilingual DISKHA platform (National Digital Infrastructure for Teachers) was expanded and now contains e-Learning content for students, teachers, and parents aligned to the curriculum, including video lessons, worksheets, textbooks and assessments. The app has more than 80,000 e-Books for children of grades 1 to 12 and is available to use offline. In addition, the pre-existing SWAYAM platform for free massive open online courses (MOOCs) was expanded with new material covering a variety of topics. SWAYAM covers material from grade 9 upwards.

In Indonesia, the Ministry of Education and Culture through the Center for Data and Information Technology launched Learning Accounts with the learning.id domain. The electronic account can be used by students, educators, and education personnel to access electronic-based learning services.

In Italy the Ministry of Education and Culture set up a comprehensive website for schools, teachers and students. Schools can gain access to digital remote learning platforms such as Google Suite for Education and Microsoft Office 365 free of charge and provide accounts to their teachers and students. Online resources from UNICEF, the National Broadcasting Service (RAI), Telefono Azzurro and other foundations are also included.

Kenya initiated a ‘Kenya Education Cloud’ with free access to electronic copies of all textbooks as well as educational exercises. Moreover, despite primarily relying on TV to disseminate education lessons, Kenya has also been using YouTube for VODs of the TV broadcasts, accessible by all that have internet access. Private company Safaricom (the largest telecom provider) has been providing free access to its own Shupavu291 platform, the second-largest education platform in Africa (Eduzu education), for primary and secondary school children.

In Kuwait, the government delayed its decision to use online teaching for several months but eventually started utilising distance learning through an online platform in August 2020 (12th grade) and in October 2020 (all other levels).

In Latvia, remote learning was introduced across educational levels. The main platform for schools is E-klase, with additional services provided by Uzdevumi.lv and Soma.lv.

In Luxembourg, the government expanded the SCRIPT (Service de coordination de la recherche et de l’innovation pédagogiques et technologiques) platform to include learning materials, daily competitions & support resources available to teachers, students & parents.

In Mauritius, a host of educational programmes was provided online to students with a total library of almost 5,000 videos on subjects taught at Primary and Lower Secondary Schools. Moreover, 8,500 educators and 50,000 students were provided Office 365 by the government. The Ministry also renewed and upgraded Microsoft licenses to provide more features and value by moving to Cloud with some 100,000 full licenses that can be installed in student devices both in schools and their personal machines.

In Mongolia, 480 online courses and 206 textbooks have been uploaded to their educational website, and so far have reached more than 100,000 users.

Morocco provided an online learning programme named Telmid TICE, which centralised educational resources for virtual learning. Uptake was lowered due to technological issues and lacking internet access in some areas.

In Namibia, the government developed packages designed to be taught simultaneously across online learning platforms and technological devices such as tablets, smartphones and laptops, depending on the resources of the student.

In Nepal, the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology introduced a learning portal, which features digital content like interactive learning games, videos of classroom lessons, audio, and e-books. This content is categorized according to grade and subject for easier navigation and is overseen by Nepal’s Curriculum Development Center. Across five districts, this is benefiting more than 100,000 children in grades 1-10.

In New Zealand, the Ministry of Education set up a new website for online education resources and guidance called Learning from Home which provides fundamental schooling at home. In addition, the new ClassroomNZ2020 online learning platform offers schools and students optional access to additional online courses developed by Te Kura, a state-funded distance education provider. While they do not replace online teaching done by schools, they ensure that every student in New Zealand has access to an entirely remote curriculum.

In Nigeria, the Ministry of Education announced a free e-learning portal intended to create access to online education across the nation (schoolgate.ng and mobileclassroom.com.ng).

In Oman, a new platform provides students with access to interactive educational content and interaction with their teachers during school closures.

In Saudi Arabia, the Ministry of Education launched an iEN YouTube Channel to compliment its traditional TV broadcasts. A new platform, vschool.sa, launched within a week of school closures.

In the Seychelles, the Ministry of Education has established a repository of educational resources under its E-Learning Centre on the ministry’s website (www.edu.gov.sc), containing lessons for primary and secondary students. Additionally, this platform features a catalogue of online educational resources, including Open Educational Resources.

In Paraguay, the Ministry of Education produced an online platform‚ TuEscuela en Casa (Your School at Home), that included educational materials and also included free access to Office 365 Online for teachers and students, among other initiatives.

In Peru, the Aprendo en Casa platform supplements television and radio broadcasts with an online platform, with learning guides, audios, videos, workbooks and other materials available by level and by grade, 24 hours a day.

In the Philippines, a new programme streamlines the K-to-12 Curriculum into the Most Essential Learning Competencies (MELCs), to be delivered in multiple learning modalities and platforms, including digital self-learning modules.

In Rwanda, the Rwandan Education Board (REB) has a functional e-learning platform that is being used for sharing learning resources and materials for teachers and students. Digital content is aligned to the curriculum to support teaching and learning, addressing skills including communication, collaboration, creativity and critical thinking.

In South Korea, the Ministry of Education expanded the online education IT infrastructure. Extra servers were added for the two major online learning platforms, the Korea Education and Research Information Service’s (KERIS) e-Learning Site, and the Education Broadcasting System’s (EBS) Online Class Platform.

In Sri Lanka, free and concessionary access packages for platforms such as Zoom and Microsoft teams services were provided to schools and students via internet service providers. Servers associated with Learning Management Systems were zero-rated by order of the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission to ensure free access. New servers were created to host educational content related to studies.

In Tunisia, the Ministry of Education has set up a video conferencing tool based on Jitsi, which is a set of open-source projects that allows faculty members to easily build and deploy secure video conferencing solutions, to assist them in holding synchronous classroom sessions with their students. CCK has also set up a VPN-SSL to help the entire academic community in securing access to e-learning platforms and scientific resources.

The Uruguayan government implemented the ‘Ceibal en casa’ (Ceibal at Home) program, which included a versatile learning management system (LMS) with communication features, digital learning platforms, and more than 173000 educational resources, including adaptive solutions and gamification. The Ceibal en casa program reached approximately 90% of primary and secondary students and 95% teachers.

Zambia launched a national e-learning portal for grades 8-12 for online secondary education in April 2020.

In Zimbabwe, the national educational radio programming was supplemented with online provision of learning materials.

Extracurricular activities

In Azerbaijan, the government provided various online extracurricular activities for school children, such as online chess tournaments, online arts competitions (painting, singing, playing musical instruments), as well as the ‘Scientist for a day’ competition in cooperation with NASA.

In Luxembourg, the government launched or expanded online platforms for extracurricular activities for children aged one to 12 years (National Youth Service) as well as for online fitness activities, challenges & exercises for kids, youth & adults (Ministry of Sports; Ministry of Education, Children & Youth; National Youth Service; & ENEPS).

Ensuring a good internet connection

In Canada, the provincial government of Ontario worked with school boards to deliver sustainable, modernised networks with improved broadband speeds for schools (which could potentially allow teachers to broadcast from schools) and invested an additional $150 million to improve rural broadband internet and cellular service.

In the Cayman Islands, the government established partnerships with local companies to provide internet access for students and teachers.

In Costa Rica, the Ministry of Education is working to provide circa 46,500 homes with a computer or internet connection. The Costa Rican Electricity Institute (ICE), the government-run electricity and telecommunications services provider, doesn’t charge users for accessing MEP websites.

In England, under the Get Help with Technology programme, students affected by the pandemic can apply for internet access support through increased data for mobile phones, or 4G wireless routers.

In Indonesia, the Education and Culture Ministry distributed phone credit and internet data packages for both students and teachers. These packages were transferred directly to the students and teachers’ phone numbers registered with local education agencies.

In Italy, the government invested €85 million in digital education within the ‘Decreto Ristori’ (Restorations decree). Investments were allocated to each region according to their needs. The decree should ensure 200,000 new devices are distributed and 100,000 new internet connections are established for children in need. A previous decree approved in March 2020 called “Cura Italia” (Cure Italy) with similar investments enabled the distribution of 432,330 new devices and the establishment of 100,000 new internet connections.

Until its closure in March 2021, Kenya cooperated with Google to have more than 35 of Google Loon Balloons floating over Kenyan airspace carrying 4G base stations just in order to provide online education. 35 balloons were deployed covering 50,000km2 providing service for tens of thousands of students; however, they were later stopped due to major advances in permanent internet infrastructure. The government has also pledged increased electricity provision in rural areas and to provide mobile charging units to charge devices in areas not covered by the national electricity grid.

In Malaysia, the government provided an internet allowance to bottom 40% (“B40”) families for them to access the internet and continue online learning. This allowance enables students to get free internet access for online learning.

In Namibia, the education ministry launched its own e-learning platform. Despite the push for online learning, less than 2% of the people were able to access the e-learning platform. In order to tackle this issue, the government invested N$9.4 million in internet connectivity and N$1.2 billion in Namibia Students Financial Assistance Fund (NSFAF).

In the Philippines, the government is providing free internet access at new wireless hotspots for students to use for online distance learning.

In South Korea, students have received free mobile data access to education websites through a zero-rating policy in cooperation with the three major communications companies (KT, LG, and SK). Also, to fully support students from low-income families, the government installed Internet service at their homes and provided a monthly subsidy of US$17 for internet fees.

The Tunisian Computing Center al Khawarizmi (CCK) has been entrusted by the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research to sign contracts with the country’s three main telecom operators. This collaboration will grant Tunisian students free 4G access and ensure that they benefit from the possibility of accessing digital platforms available for distance learning.

In Vietnam, the main internet operators (Viettel, VNPT, MobiFone, and Vietnamobile) offered free mobile data charges for students, teachers and parents when using the online training solutions announced by the Ministry of Education.

Increasing access to equipment

In Bermuda the Ministry of Education in Bermuda issued iPads with the Preschool Adaptive Learning Platform ‘Hatch’ to preschool students and Chromebooks to students at other levels, and Preschool Adaptive Learning Platform to teachers delivering lessons remotely.

In Canada, the Provincial government of Newfoundland and Labrador funded the purchase of more than 5,000 laptops for teachers and in excess of 30,000 Chromebooks for Grades 7-12 students.

In the Cayman Islands, the government started a ‘one-to-one’ laptop initiative that plans to give every student in government schools access to a laptop. By October 2020, 60% of the 4,600 students in government schools had been loaned a laptop from the Ministry of Education.

In China, some provinces have subsidised students to gain access to online studies. Liaoning Province, for example, has paid a total of 7 million RMB (1.08 million USD) to around 20,000 students from higher education institutions in the province to buy equipment or pay for internet access.

In Cyprus, eligible students can apply for a grant to subsidise the purchase of laptops.

In Denmark, the Ministry of Children and Education’s Special Educational Support service delivered technological devices to eligible children and offered virtual diagnostic testing in case of issues.

In England, the Department for Education (DfE) is providing laptops and tablets for students who cannot access face-to-face education.

In Germany, the federal government has provided an additional 500 million euros to equip students from poor households with devices such as laptops so that they can fully participate in distance learning. States and schools are tasked with distributing the devices.

In India, the state governments of Lakshadweep and Jammu & Kashmir distributed tablets equipped with e-contents to students and braille tactile readers for visually impaired learners.

In Italy, the March 2020 ‘Cura Italia’ (Cure Italy) approved by the national government provided 432,330 new devices to students in need. Successive investments in the ‘Decreto Ristori’ (Restorations Decree) should ensure the distribution of a further 200,000 new devices.

In Japan, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) organised the donation of terminals and routers by private companies for children of low-income families.

Kazakhstan started online learning from March 16, 2020. To assist with online learning, the government distributed 500,000 computers to children from families in need by August 2020. Televised lessons were recorded and could be accessed by visiting the Ministry of Education’s website.

Liechtenstein loaned laptops to school children to enable them to work remotely. School administrators have received an order to report device “bottlenecks” in families (whereby multiple children would need to access the same laptop at the same time to participate in remote classes) to the school office so that digital loan devices can be made available. Reports on whether students had access to their own device were reported to be: primary school 87%, high school 94/95% (though the report did not not specify whether the device was loaned or not).

In New Zealand, 2,000 modems and 20,000 laptops were given by the Ministry of Education to low-income students.

In Peru, the government started a programme to procure devices that would aid in closing the digital gap for students in rural areas. It was intended for students from 4th grade to 5th grade, as well as more than 90,000 teachers.

With only 58% of the children having an electronic device, the Land Bank of the Philippines, a government owned bank, started allowing students or parents of students to borrow money to buy electronic equipment so they can study online.

In Portugal, The Ministry of Education (ME) began the phased implementation of the Digital School Programme based on four cornerstones (equipment, connectivity, teacher training and digital teaching resources), with particular emphasis on access to equipment and mobile connectivity. Public Schools will be provided with computers, with priority given to students who receive school social support.

In Puerto Rico, $250 million was provided to buy tablets, laptops, and software to increase accessibility, as many students have very limited internet access.

In Slovakia, the Ministry of Investments, Regional Development and Informatisation, Single Digital Gateway portal (slovensko.sk) is continuously updating a list of companies which have decided to provide assistance in the form of preferential or free provision of technologies, solutions, and virtual education for schools and students.

In South Korea, the government provided free device rental services. Students from low-income families without digital devices were given priority to borrow devices from their schools. The private sector also donated devices.

In the United States, states differed in increasing access to devices. Florida encouraged the use of CARES Act funding given to local school districts to help solve this, Georgia used a survey to identify families that required help with accessing the internet to then grant targeted funds to specific school districts while Indiana and Montana provided a list of low-cost internet providers. In Connecticut, 60,000 devices were distributed to students.

In Vietnam, the Education Ministry offers free server rental and free device rental, as well as increased bandwidth for distance learning for universities and schools.

Teacher training initiatives

In Bangladesh, an online platform for remote teacher training was set up and monitored to find obstacles to learning, with longer-term plans of building capacity by enhanced remote teacher training and professional development.

In Bhutan, teachers were trained in IT and supported by the Ministry through social media channels.

In Denmark, the Ministry of Children and Education (MoCE) provided guidelines for teachers on distance learning, including suggestions for conducting distance lessons and how to design lessons that the students could complete at home using digital and/or analogue resources. MoCE additionally established a coronavirus hotline for educational institutions and a comprehensive set of constantly updated frequently asked questions.

In England, under the Get Help with Technology programme, the Department for Education (DfE) is providing funded training for schools to set up and use technology effectively from expert EdTech Demonstrators. The government also provided guidance on following safety procedures when planning remote education strategies and teaching remotely during COVID-19 including digital wellbeing, technical instructions (including recommendations for schools on selecting and setting up video conferencing options safely and with the appropriate privacy settings).

In Estonia, guidelines for distance-learning environments were offered at the state level. The government also launched Facebook groups and FAQ websites aimed at teachers to answer questions about management and organisation of students’ studies. Moreover, the government offered a remote support hotline to assist teachers.

In Hong Kong, teachers were given different strategies to adapt diversified teaching materials for interactive learning either at staggered times and on different internet-accessible devices.

Under the Resilience of Broadcasting of Education Content policy plan, Kenya has outlined objectives to extend existing distance learning programmes, building capacity of Ministry of Education officers to provide training and support to teachers in the event of future outbreaks, as well as specific programmes for marginalised learners, including girls and special needs learners.

In Luxembourg, the government launched a peer support platform for secondary school teachers to connect & share best practices related to distance learning. Moreover, they launched a helpline with 100 educators on standby answering calls from students, teachers & parents to help them navigate this new way of learning.

In New Zealand, teachers and education leaders were provided access to more professional learning and development (PLD) to support them to work remotely with their students.

In Slovakia, the Ministry of Education created a portal to help teachers deliver online education in cooperation with several non-governmental organisations, and experts. A hotline was also set up where experts provide advice and answers to questions related to the situation in education. Some of the educational support for schools was also aimed at aiding ethnic minority groups directly, with 33 such projects using languages Hungarian or Ruthenian as the language of instruction.

Eliminating non-infrastructure barriers to learning

In the Cayman Islands, the government established partnerships to provide COVID-19 counselling support for students and staff.

In England, additional support and resources for parents and carers to keep children safe from online harm was made available, including details of specific online risks and how to manage them, advice on security and privacy settings, content blocking, and parental controls.

In Estonia, remote support for technical and pedagogical advice for parents and students was offered by the government.

In India, following a survey on online learning, the National Council for Educational Research and Training (NCERT) has developed an Alternative Academic Calendar and Guidelines to enhance students’ learning with a focus on filling the gaps caused by school closures. The state governments of Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal started a free phone and video call centre for students to help them to understand critical topics.

In Japan, the government issued guidelines enabling students, parents, and teachers to create an environment where online learning can be conducted at home. It also offered advice on how to ensure information security.

In Kenya, the government developed a risk management matrix to address challenges associated with remote learning including addressing online risks of abuse and grooming; vetting and regulating e-learning delivery systems; education and awareness on online safety for learners and parents to block unwanted content; and limiting access to specific kinds of content online for learners using digital tools.

By mid-April 2020, the Luxembourg government had implemented an ‘extraordinary’ family leave program to free up parents for their new level of involvement. The law stipulates that a parent can take leave if they have a child at home that is required to learn from home and is below the age of 13; or if the child is ordered to stay at home via a quarantine order; or if the child is ‘vulnerable’ to COVID-19 infection (and hence stays away from school even if schools are open).

In New Zealand, the government connected so-called ‘Learning Support Coordinators’ with families remotely.

In Norway, the government launched a grant scheme for local initiatives that aim to support distance education, and committed to compensating municipal and private kindergarten providers for lost income to ensure their survival.

In Rwanda, a helpline was created for parents, students, and community members to support their queries related to remote learning options, as well as to generate feedback on the efficacy of resources. SMS services are used to communicate important messages and reminders for parents on learning schedules of children. Children with disabilities are provided access with digital formats of communication such as translating the REB scripts into Braille, close-caption and Sign Language. Teachers are supported through mobile credit to be able to call to the most vulnerable students and provide remote support and tutoring.

In Vietnam, telecoms providers and social networks in Vietnam supported an effort to text information from the Ministry of Education to students, teachers and parents.

Use of television/radio broadcasts to increase education accessibility

In Georgia, due to limited internet access, the Ministry of Education worked with Georgian Public Broadcaster (GPB) to deliver live lessons for students from March 30, 2020. The lessons were available in Georgian, Armenian and Azerbaijani.

As part of Kenya‘s basic education COVID-19 emergency response plan, the government provided regular radio and TV live broadcasts, including broadcasting through community radio channels.

Azerbaijan launched a televised online vocational education and training resource for students on March 30. The online courses – which have launched on the Culture TV channel and other platforms – include 26 lessons across eight VET specialisations, including electrical engineer, construction, mechanics, automobile and ICT.

In Morocco, lessons were broadcast through various TV channels (Laayune TV, Athafiqa, Tamaghirt TV) to make up for those without access to online learning.

In Cuba, classes were broadcast on TV and Radio to compensate for accessibility inequalities. They had preexisting channels such as Cuba Educa dedicated to education so could make use of this existing infrastructure. 4000 schools (slightly less than 50%) were connected to the network as of 28 April 2020.

Albania has developed courses that air on national TV channels and radio (E.g. Akademi.al, RTSH Skolla, Radio RTSH) to increase accessibility.

In Bangladesh, Sangsad TV, a government owned channel, broadcast lessons to provide education. The government also cooperated with UNICEF to develop learning for formal, non-formal, religious, and technical education. This was targeted primarily for Grades 6-10. The Education Minister suggested that this online teaching has reached 87% of students.

In Cambodia, students from pre-school to upper secondary could tune into TVK2, a Cambodian television station launched during the pandemic. Grade nine through 12 students became a priority for online learning ahead of national examinations, and the Ministry provided pre-recorded lessons for all grade levels on its Facebook page, YouTube channel, and e-learning website. Learners could also follow learning programmes via Telegram, Zoom and Google meetings, and as well as Multilingual Education and Cambodian sign language online and on television.

During school closures in Bhutan, content was broadcast on TV/radio on dedicated education channels. For younger children, lessons were only offered in Mathematics, English, Dzongkha. For classes seven to 12, the lessons are theme-based selected from the syllabus.

In Botswana, the government partnered with local cell phone providers to offer free service to access educational contents. Weekly SMS and phone calls from teachers to students for basic numeracy and literacy.

In Czech Republic, the Czech national TV broadcasts educational programming for pupils under the expert supervision of the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport (MEYS).

In India, Swayam Prabha, a national television service, broadcast programmes aimed at children who were not connected to the internet and had limited access to radio & TV. The state of Nagaland distributed study material through DVD/Pen drive to students. In remote areas where both internet connectivity and electricity are sporadic, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Dadra & Nagar Haveli and Daman & Diu distributed textbooks at children’s doorsteps.

Kenya has been primarily relying on TV and radio to disseminate education lessons.

In Mauritius, a host of educational programmes were broadcast on the national TV channels with a total scope of more than 5,000 videos on subjects taught at Primary and Lower Secondary Schools.

In Mongolia, the government has prepared tele-lessons in several languages such as Mongolian, Kazakh, Tuvan and sign language which are available to the students, their parents, and teachers and are being delivered on 16 different television channels with a fixed daily schedule.

In Namibia, the government developed packages designed to be taught simultaneously across radio/television educational programmes, online learning platforms and technological devices such as tablets, smartphones and laptops, depending on the resources of the student.

In New Zealand, two television channels broadcast education-related content – one in English and the other in Māori. They include content that is targeted to Pacific and other communities. Moreover, students in areas where the internet is not accessible were provided with hard-copy packs of materials for different year levels.

In Vietnam, the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) issued policies allowing provinces to conduct mass teaching via television. Broadcast schedules of lectures for students to engage with learning has been widely announced, especially for students in exam years. There are 14 television channels broadcasting general education lectures. The Ministry of Education and Training has released the data of 5,000 general education lessons to be used for free.

In Sierra Leone, the Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education, with support from Education Development partners, launched a radio-based distance teaching programme. Students receive free daily lessons from qualified teachers who deliver the structured lessons from a UNICEF studio. The subjects are taught in line with the current national curriculum.

In South Africa, a pilot intervention offered SD cards with educational materials, past exam papers, and readings for Grade 12 students to access offline courses.

In the Seychelles, the education ministry has been broadcasting specially prepared educational content for students on the two main TV channels: Seychelles Broadcasting Corporation (SBC) and Telesesel. The lessons are broadcast five days a week and are aligned to the National Curriculum.

In Oman, TV channels provide educational classes for grade 11 and 12 students, according to a regular schedule which includes all subjects.

In the Philippines, selected teachers were trained to be teacher-broadcasters by the country’s top journalists to deliver lessons through the Department Education TV channel, since not all areas in the country have an internet connection.

Both Fiji and Vanuatu provided education through radio programmes for all age groups.

Appendix

Report authors: Andrew Wood, Tim Nusser, Martina Di Folco, Helen Tatlow, Naomi Simon-Kumar, Toby Phillips, Tatjana Buklijas

Contributors: Ariana L. Detmar, Anthony Sudarmawan, Jiayi Li, Shiwen Lai, Ariq Hatibie, Nicole Wu, Xingyan Lin, Qingling Kong, Akhila K Jayaram, Tiwalade Ighomuaye, Victoria Cavero, Israa Mohammed, Sheku Bangura, Teki Surayya, Saroj Jayasinghe, Aishwarya Lakshmi Vidyasagaran, Muhammad Djindan, Purity Rima Mbaabu, N. J. Umuhoza Karemera, Kristoffer B. Berse, Tomáš Michalek, Keith Kiswili Julius, Pradeep Kumar, Lianne Angelico Depante

Table 1: Summary of initiatives discussed in this report

| Country | Summary |

| Azerbaijan | Online extra-curricular activities |

| Argentina | Developed a free digital platform dedicated to online learning called “Seguimos educando”. It provides students, families and teachers with an array of resources through different media platforms (radio, TV, etc.) |

| Bahamas | Live and recorded lectures with associated activities online. |

| Bangladesh | Remote online training for teachers |

| Benin | SMS messages and online distribution of educational materials |

| Bermuda | “Hatch iPads” and Chromebooks distributed |

| Bhutan | Lectures were broadcast on YouTube and through Google classroom. Younger children (0-12) only had access to restricted subjects or topics. Training for teachers in IT. |

| Botswana | Local mobile companies helped to provide free access to online educational content. |

| Canada | Laptops for students and staff and modernisation of internet provision. |

| Cayman Islands | Government partnership with private companies to provide laptops and internet services. |

| Chile | Online learning, teaching, and training platform called “Aprendo en Línea”. |

| China | Online education platform for primary and secondary school students. Funding to allow students to buy internet or laptops. |

| Costa Rica | New website with educational resources for teachers and students. Government owned-energy company does not charge for electricity or the internet for accessing educational websites. |

| Czech Republic | New website containing links to online educational tools, updated information and examples of good practices. |

| Cyprus | Grants for laptops |

| Denmark | Microsoft Office 365/Teams and Google G Suite for Education available to all schools free of charge. Technological assistance and virtual diagnostics. Issued advice to teachers on how to set up distance learning |

| Egypt | Educational Knowledge Bank set up |

| Estonia | Remote technical support for parents and students, FAQs and facebook groups for teachers |

| Fiji | The government provided online education through a website, a Moodle platform and other media platforms. |

| France | New platform called “Ma classe à la maison” accessible by all students. |

| Germany | Laptop distribution from schools. |

| Hong Kong | New strategies to adapt teaching materials for online working at staggered timings, expanding use of existing platforms. |

| India | Expanded the pre-existing multilingual platform to include e-Learning content for students, teachers, and parents according to curriculum. Tablet distribution to students, including braille tactile readers. |

| Indonesia | Launched “learning accounts” for both students and teachers to access e-Learning services. Distribution of mobile phone credit and internet data packages. |

| Italy | Devices provided by schools, increased internet provision |

| Japan | Increased terminal and router distribution to schools. Guidelines for creating the right environment for online education |

| Kazakhstan | Government distribution of laptops |

| Kenya | “Kenya Education Cloud” with free access to textbooks and online resources. It also provided lectures through television and YouTube. Safaricom, a private telecom provider, made access to an educational platform free of charge. “Risks of online” management matrix |

| Kuwait | New online platform for remote learning. |

| Latvia | Remote learning is provided through the online platform E-Klase, in addition to educational TV channel Tava Klase. |

| Liechtenstein | Laptop loans from schools. |

| Luxembourg | Peer support network for teachers, family leave programme, new online learning platform |

| Malaysia | Internet allowance given to lowest earning 40% families. |

| Mauritius | Free Microsoft Office licenses for both school-owned and private devices. Remote learning is provided through an online library. |

| Mongolia | Online courses and textbooks were uploaded on an online educational platform. |

| Morocco | New “Telmid ICE” platform which provides educational materials |

| Namibia | Designed courses to be taught simultaneously across online learning platforms. Launched an e-learning platform and invested in greater internet connections to widen access to it. |

| Nepal | New learning portal overseen by Nepal’s Curriculum Development Center. |

| New Zealand | New online platform called “ClassroomNZ2020” and released “Learning from Home” guidelines. Some low-income students were provided with devices. |

| Nigeria | Two new online learning platforms, in addition to providing radio and television broadcast lectures. |

| Norway | Grant scheme for local initiatives that support online learning |

| Oman | New remote learning platform |

| Saudi Arabia | Remote learning platform “vschool.sa” was launched, in addition with a strengthening of the Ministry of Education’s channels network. |

| Seychelles | New online repository of educational resources under its e-learning centre. |

| Slovakia | New portal for teachers |

| Paraguay | Online platform called “Tu Escuela en Casa” launched. |

| Peru | The e-learning platform “Aprendo en Casa” supplements radio and television broadcasts with an array of educational resources. Government procurement of devices. |

| Philippines | Free internet in educational institutions. Government-owned bank allows students to borrow money to buy electronic equipment so they can study online. |

| Portugal | Schools provided with computers to distribute to students who receive social support. |

| Puerto Rico | Government purchase and distribution of devices. |

| Rwanda | New e-learning platform for teachers and students. Helpline for use of remote learning |

| Slovakia | Portal with list of companies providing free/reduced services for students |

| South Korea | Expanded e-learning site, and the Education Broadcasting System’s online class platform. Free mobile data access to education websites. Programme for laptop loans from schools. |

| Sri Lanka | Internet service providers provided schools and students with free and concessionary access to platforms such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams. |

| Tunisia | New video conferencing tool, free 4G mobile data was made available for students, as well as video-conferencing and VPN-SSL to secure access to e-learning platforms. |

| UK | Funding to acquire Google G Suite for Education or Office 365 Education through the “Get help with technology” programme. Students can apply for increased internet access support, via 4G wireless routers or mobile phone data. Laptops are also being provided. |

| Uruguay | “Ceibal en casa” program, consisting in remote learning platforms and services for teachers, students, and their families. |

| USA | State variation with some providing devices, some assisting with low-cost internet provision and some encouraging the use of CARES funding for internet and devices |

| Vanuatu | Website, a Moodle platform and other media platforms. |

| Vietnam | Main internet operators offered free mobile data to students when using government education platforms. Free device loaning and server space, as well as increased internet bandwidth. |

| Zambia | National e-learning portal for grades 8-12. |

| Zimbabwe | National educational radio programming was supplemented with online provision of learning materials. |