Mind the social class gap: how COVID-19’s unequal income shock hit the UK’s have-nots hardest

While most people’s income was negatively affected by the pandemic, a close look at the evidence shows the biggest losers were those who were already worst-off

Danny Dorling

The pandemic had an almost-immediate, and massive, detrimental economic effect on the lives of the already worst-off in the UK – especially younger adults in precarious employment, and people of Black, Asian and minority ethnicity who disproportionately had to borrow money to get by.

However, of overwhelming importance in determining who was most badly hit economically was whether a person already lived in a household that was rich, ‘average’ or poor.

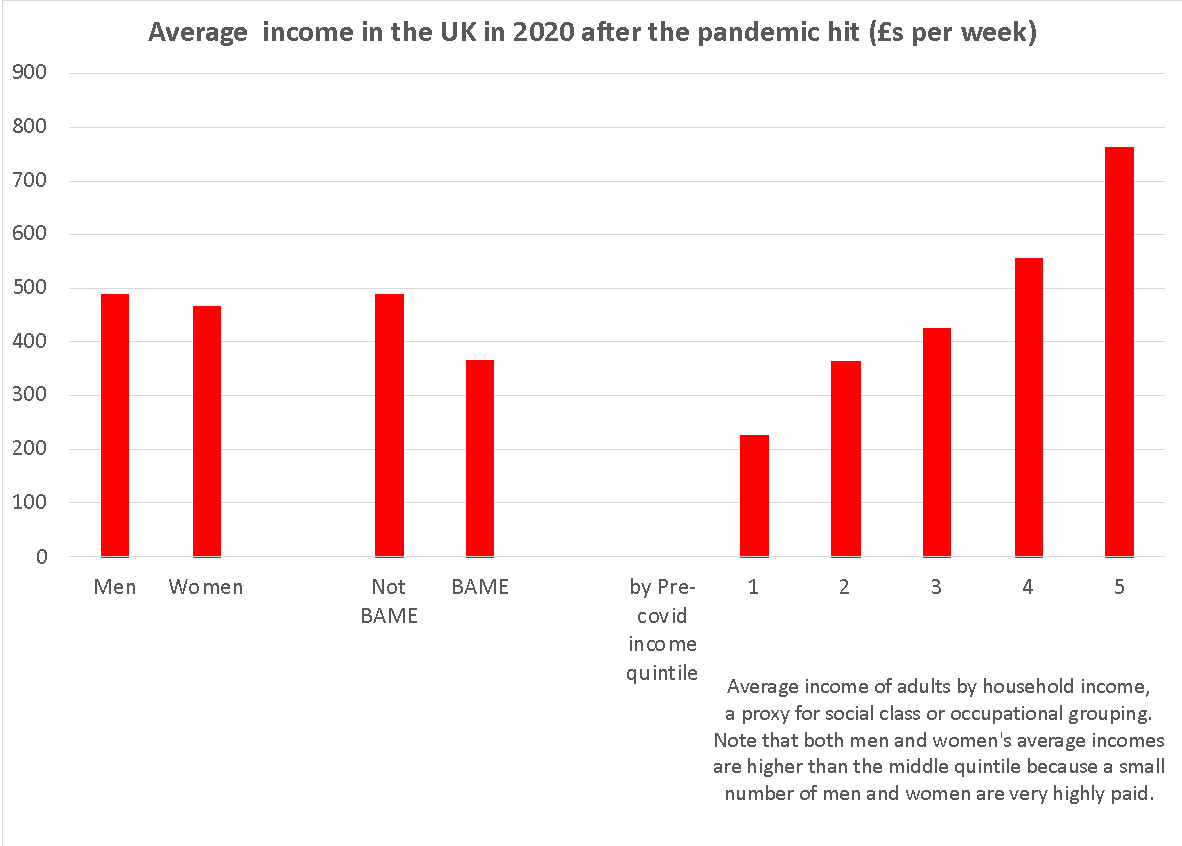

A study by Crossley, Fisher and Low, published in January 2021, spelt out what had occurred in detail using figures of income carefully adjusted for the size of each household and the number of children in it, after taxes and including benefits. It showed the average income of people living in the poorest fifth (lowest quintile) of households in the UK fell from £287 a week in February 2020 to £228 a week by May last year. This fall, of over 20%, was larger than for any other quintile group, and resulted in a huge and sudden widening of the gap between the best- and worst-off quintiles, which has probably not narrowed since then.

In contrast, the best-off fifth received, on average, income of £765 a week in May 2020 – a fall of 11% since February last year. While only half the drop in percentage terms experienced by the poorest households, this will often still have felt like a great fall in income to them. But overall, while each income quintile became less well off, the gap between the haves and have-nots widened – despite there having been a slight increase in welfare benefits for the poorest.

Which population groups were acutely affected?

The same study also revealed the groups in society who were particularly acutely affected. For example, within the poorest quintile of the population (roughly 13 million people), the quarter who had fared worst lost 60% or more of their income in these two months. In other words, 3.3 million people in these UK households lost at least £172 a week.

In contrast, the very best-off 25% of the already best-off quintile saw their income actually rise by 8% or more over the same period; i.e. at least £69 more a week for the economically most fortunate 3.3 million people in the UK. The few economic winners from the pandemic were almost all people who were already very well-off.

At the most extreme, a tiny number became dramatically richer in 2020 by winning government contracts that were not properly put out to tender. As the BBC reported (among many other scandals): ‘The government has also been accused of favouring firms with political connections to the Conservative Party with a “high-priority lane”.’ However, most of the winners were simply already well-off people who were able to take advantage of some aspect of the crisis. What matters is that it was mostly only a few people from among the best-off quintile who were best-placed to do this.

Other income-related inequalities may, in fact, have narrowed as the UK’s class gap widened. Men earned 9% more than women in February 2020, but that gap fell to only 5% by May as more men experienced bigger pay cuts – partly due to being furloughed more often. People of Black, Asian and minority ethnicities were, on average, 27% less well-off than white people in February – but that gap also fell slightly to 25% by May 2020.

The social class gap

By May 2020, there was a 5% gap between the average incomes of men and women, and 25% between white and Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. However, the income gap between the lowest-income fifth and the highest-income fifth by households was much higher: 235%, up from 200% in February. This is the social class gap.

Your fortunes depend most on your social class, what kind of job you have, or whether you have a job at all. Whether you are male or female has an impact, but it is small compared to class and it shrank as the crisis unfolded, despite the fact that women are more likely to be in jobs that are lowly paid, or not in work if a single parent of a young child. In May 2020, men in the UK were receiving on average £490 a week and women £467; three months earlier, those numbers had been £573 and £526 respectively.

The fact that the gender pay gap narrowed while the social class gap widened is because more men could be sacked or furloughed on 80% of their normal pay. This was slightly less likely for women because more women were doing work that had to continue. One very obvious example was working in health and care services, where women dominate.

The same pattern seen for women was also seen for individuals of Black, Asian and minority ethnicity: their incomes were lower before the crisis began, fell during the crisis, but did not fall as much as for some others. By May 2020, social class was 9.4 times more important than ethnicity in influencing income (235/25); before the crisis that difference had been nearer 7.4 times (200/37). Part of the reason was that people from ethnic minorities, as with women, are more likely to be key workers.

Table reproduced from Crossley, Fisher and Low (Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 193, January 2021)

None of this should be that surprising. Within any ethnic minority group, just as among women, there is huge variation in incomes – whereas within occupation groups or social classes, there is much less variation in income. However, what was perhaps unexpected was that the crisis should see the income gaps between men and women and Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups narrow, despite the income gaps widening between people overall – i.e. between those in the lowest income bracket and those in the highest.

Lone parents were especially badly hit

Despite the overall narrowing of gender inequalities, lone parents – the large majority of whom are women – were especially badly hit from the outset of the pandemic. While most lone parents are in the bottom quintile group for income, they are often poorer than the group as a whole. Four out of 10 lone parents had to rely on gifts or loans from relatives at this time, and one in eight on a food bank (compared with one in 12 for the poorest quintile as a whole).

Some 82% of the adults who went to food banks in April or May 2020 were women. Among couples, it was almost always the woman who went to the food bank. Some 85% of people who went to food banks were white, a fraction less than the overall 90% of UK adults in this population category. Two-thirds of food bank users were in the very poorest quintile of income, while virtually none were from the best-off 40% of households.

Danny Dorling is Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at the School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford. This article was first published in Public Sector Focus (March/April 2021 issue, pp. 18-19)

Source note

This analysis is based on a study by Thomas Crossley, Paul Fisher, and Hamish Low: The Heterogeneous and Regressive Consequences of COVID-19 – Evidence from High-Quality Panel Data (Journal of Public Economics, Volume 193, January 2021, 104334)