IPPO one year on: what have we learned about how to help policymakers make better-informed decisions?

A key element of IPPO’s approach is to review our experiences of bringing policy and evidence together during the pandemic – and to adjust our processes when change is needed. On the first anniversary of the Observatory’s launch, we present our latest thinking on the key challenges we must tackle to make real policy impact

Joanna Chataway, David Gough, Muiris MacCarthaigh, Geoff Mulgan and Chris Taylor

In April, we published some early thoughts on what the International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO) had learned as we began to ramp up our activities. That blog focused on what it means for IPPO to be ‘demand-led’ – and the best ways to go about developing an effective supply (of the latest and most robust global evidence) to meet that demand (i.e. what policymakers all over the UK need to know in order to make better strategic decisions).

Now, on the first anniversary of IPPO’s launch, this blog builds on that earlier thinking by discussing four issues that have loomed large in our learning during the first year of the Observatory’s existence. These are:

- Firstly, the need for ongoing iteration between supply and demand as we scope, develop and deliver each focused workstream within our broad policy topic areas.

- Secondly, the question of how far we should extend IPPO’s activities to ensure that research and evidence-informed policy advice gets implemented.

(Note: both of these issues link back to the question of how we can best try to ensure IPPO builds effective policy demand and evidence supply pathways.)

- Thirdly, we reflect on some of the pros and cons emerging from IPPO’s wide-ranging remit to work across multiple parallel policy issues.

- And finally, what does it mean for IPPO that research suggests narratives and story-telling are so important in achieving meaningful uptake of evidence? While structured and methodologically rigorous research is always critical, the chances of it influencing policy are enhanced by finding a convincing narrative or cognitive frame with which to disseminate it and convey its significance.

1. We need constant iteration to match demand with supply

IPPO’s first Systematic Review (what has been learned about online learning during the pandemic?) and four Rapid Evidence Reviews (impacts on schoolchildren / Further Education / Higher Education / parents & carers) have all been in the area of education. They followed on from our workstream developing evidence-based policy ideas on the need for social and emotional catch-up for children, rather than an overly narrow academic approach. Our research effort resulted in a suite of rigorous evidence-based products, some commissioned directly by the Department for Education.

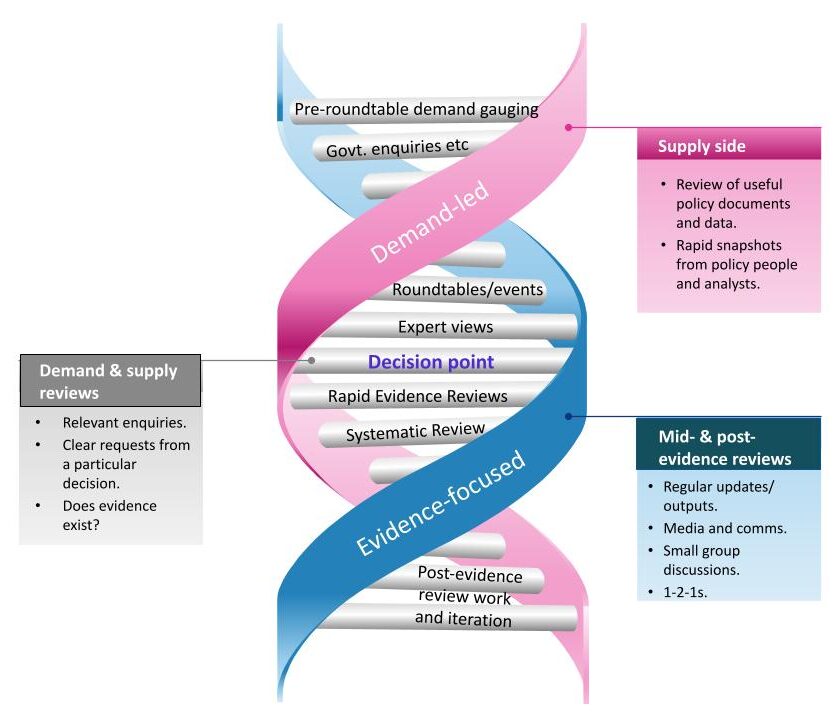

The experience of our early work has led us to move from the graphic included in this blog, explaining IPPO’s broad approach, to the ‘double helix’ model depicted here:

This double helix model better depicts the need for constant iteration between supply and demand. In particular, it highlights the importance of defining the research question(s) on the basis both of demand (what is the most useful question to answer) and supply (what can be answered based on the evidence available). This requires intensive interactions, both with existing literature and people with relevant policy experience (national and international).

We’ve seen there can often be inherent tensions in this interaction between the supply and demand sides on framing research questions. A key issue is that policymakers often don’t actually quite know what is wanted or needed from the evidence base. So early stages on the helix depict interactions between supply and demand, rather than presuming there is an already-crystallised demand. There is also the constant challenge of capturing what the evidence says: while there is bound to be resistance on the supply side to simplification, it can be essential for getting messages through.

Furthermore, the nature of the demand side can offer further challenges. Government is not a single entity, of course; there are layers of strategisers, decision-makers and communicators within government, including research teams, civil servants and politicians. Navigating this terrain takes time and sensitivity.

Nor does successful iteration end when our evidence products are finalised. Serious thought and effort is needed regarding how best to communicate these products’ key messages (including using visualisations and ‘other’ formats). This has required us to think about how far we should extend our activities to encourage the uptake of IPPO’s research (and other evidence) by policymakers as part of their decision-making.

2. How far should we go to encourage the uptake of research?

That policymakers are time-poor, particularly in the context of a crisis, should not be a surprise to anyone. It is well-documented that most public servants operate within ‘bounded rationality’, doing the best they can with the evidence that is immediately attainable to them.

In the context of COVID-19 and recovery from the pandemic, it is therefore important for researchers to listen to policymakers’ needs – as even carefully constructed research may otherwise not be sufficient to ensure the uptake of evidence.

Building on this recent blog by UCL STEaPP’s Public Policy Manager Jenny Bird, we note that in addition to the lack of a tidy match between the supply and demand sides of a particular issue, there are additional factors that might pose a problem, including:

- motivation of policymakers to adopt the evidence;

- uncertainty over which evidence to prioritise;

- changes in political orientation and priority;

- changes in political and economic context;

- insufficient resources for implementation; and

- the absorptive capacity of those tasked with policy design and implementation.

Clearly, the degree of control that researchers have over policymaker motivation is limited – and even less so over both political direction and resources for implementation. However, ignoring them is unhelpful – as Paul Cairney, Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of Stirling, pointed out in this paper.

The absorptive capacity of decision-makers can be particularly limited during times of crisis – and is hugely difficult for researchers to deal with. As an outside party to government departments and other organisations with direct responsibility for policy design and implementation, the degree of control that IPPO or any other policy research initiative has is very limited. The resource allocated for the work we do does not facilitate taking a hands-on role in implementation – and in any case, some separation between evidence providers and those engaged in implementation may be beneficial.

One option that we are exploring in our work on basic income and other areas is to develop principles for policy design and implementation. The idea is that in developing principles, rather than detailed implementation plans, we are a) recognising our limitations in relation to implementation, and b) building flexibility into the policy thinking that we develop so that policymakers can use the work at the times and in the contexts that suit their needs. We will have more to say about this approach as the work progresses.

3. What are the pros and cons of being a broad-based initiative?

IPPO was set up to synthesize, and then make accessible, knowledge and evidence across a broad range of policy topic areas, from mental health and social care to education and vulnerable communities. Rather than trying to incorporate subject expertise of all kinds in-house, our plan is to work with experts in particular fields who complement the policy and research skills within the IPPO team.

The fact we are a broad-based initiative with methodological and policy expertise at its core, rather than specific subject matter knowledge, has its strengths. Experts in a field tend to develop their perspectives and opinions over years in ways that help them navigate the subject matter terrain. Providing dispassionate methodological expertise can be important to making sure that subject matter incumbents are not unwittingly limiting the scope of their investigations and evidence gathering.

The breadth of IPPO, incorporating staff who are experienced in constantly developing partnerships and collaborations with decision-makers, means we can be flexible and adaptable. This has real advantages in a policy landscape that can shift dramatically over even short periods of time. For example, together with subject specialists, we have been able to deliver work on pressing issues to do with online distance learning effectively and to a high standard, and also to make positive connections between different policy areas.

There are, however, potential downsides to the IPPO structure. For example, searching for topic specialists who are both interested in the work IPPO is doing and have the time to help can be time-consuming (although to date, IPPO has been lucky on this score: we have been helped in developing contacts and networks by initiatives such as CAPE and UPEN, initiatives that have helped us link up with talented researchers interested in policy- and knowledge-exchange).

Secondly, not having subject expertise integrated into the core IPPO team means we have to constantly develop policy networks. Evidence ecosystems require policy and research actors to engage with each other; IPPO provides infrastructure to enable such ecosystems to function productively, but the shortcuts available to people who have built up contacts and knowledge about ‘who’s who’ over years are not always immediately available to us. On the other hand, our experience at IPPO is that not all researchers have well-developed policy networks, while we can add value precisely by helping to navigate different routes to impact.

Thirdly, the media can be a vitally important part of building reputation and profile; in turn making it more likely that research and evidence will be listened to and acknowledged. Without specific topic expertise in IPPO’s core team and by having a broad policy topic remit (in comparison, say, with the more focused UK in a Changing Europe), the familiarity between specialist journalists and researchers which, over time, attracts the attention of policymakers is perhaps more difficult for IPPO to develop.

4. Why storytelling is a key factor in getting evidence noticed

Ideas, narratives and the framing of research are often essential to getting evidence noticed by policymakers. This widely-held view was recently confirmed by a study by Leire Rincón García that looked at how policymakers engage with evidence. Strikingly, it held true regardless of the rigour of the research.

The implication for IPPO is that our focus should not only be on developing rigorous evidence, but on understanding the ways this evidence relates to narratives that policymakers find compelling at any particular time. This requires careful listening. Policy narratives change, and particular policy framings ebb and flow all the time.

‘Big’ narratives tend to change more slowly, but their rise and demise is still evident. Language supporting free markets has changed from the era of Thatcher even amongst those who support essentially free-market policies. The narrative of South Africa as a ‘rainbow nation’ doesn’t hold the same power that it did two decades ago.

None of this is to suggest that evidence should be led by the narrative and story; simply that rigorous evidence on its own will not necessarily speak loudly enough for policymakers to hear it and see where it fits in current conceptual frameworks.

There are a number of further implications for IPPO. The first is that communication is key to our efforts, so we must devote considerable time and energy to crafting clear, evidence-led messages that resonate with current policy narratives and framing. Perspectives from those deeply involved as practitioners, or who have been impacted by policy decisions, can be affecting and powerful. The vividness of lived experience is more convincing than evidence alone.

Finally, people often find it easier to absorb arguments and ideas through an example or case study rather than through over-aggregated materials. This seems important for IPPO products. From global scans to different types of evidence synthesis, we potentially need to pivot to highlight individual cases, policies and projects alongside the aggregate ones.

Professor Joanna Chataway is IPPO’s Principal Investigator; Professor David Gough and Professor Sir Geoff Mulgan are IPPO’s Co-investigators. Professor Muiris MacCarthaigh and Professor Chris Taylor are IPPO’s policy leads in Northern Ireland and Wales, respectively.