The impact of COVID-19 on youth unemployment in the UK: key regional differences and long-term trends

IPPO and Youth Futures Foundation recently co-hosted an expert roundtable to assess how UK cities should tackle youth unemployment in their COVID recovery plans. This topic snapshot offers a regional perspective of the challenges they face

Overview

Since the 2008 financial crisis, the gap between older and younger workers has grown. Young people tend to be overrepresented in sectors that are forecast to see lower employment long term, for example because of structural decline such as hospitality, retail and support services. Young people are also over-exposed to jobs that face the highest risks from increasing automation. The pandemic has only made things worse.

Despite more than a million youth jobs being protected through the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (aka furlough), there was a dramatic, initial impact on youth employment with more than 425,000 jobs lost one year into the pandemic among 16-to-24 year olds.

Overall, young people accounted for nearly half (46%) of the total fall in employment during the first year of the COVID crisis, and young people have seen a far greater fall in employment compared with other age groups – with employment still more than 6% below pre-crisis levels at August 2021.

In response, many young people have either stayed in – or moved into – education:

- Youth participation in full-time education has risen to its highest rate on record (48%, compared with 43% before the crisis began), while the youth employment rate has fallen to close to its lowest-ever level (53%, compared with 55% before the crisis began).

- There are 170,000 more young people in education and not looking for work than before the crisis began. This is contributing to employer difficulties in filling entry-level jobs, especially where those roles are not being advertised flexibly (for example, in ways that can fit around studies).

To an extent, this increased participation in education is masking the widening of existing inequalities in the youth labour market due to the pandemic. For example:

- Increased polarisation between high- and low-skilled jobs, so there are fewer ‘stepping stone’ mid-skills jobs and more young people in insecure and part-time work.

- Those with a health condition or disability, as well as young parents, are most likely to be unemployed for more than six months.

- Young people who are Black or Asian are more likely to be unemployed than young white people. The COVID-related fall in employment rates being four times greater for young Black people than for young white people, while the fall for young Asian people has been nearly three times greater.

In addition to being overrepresented in the sectors hit hardest by the pandemic (e.g. hospitality, leisure services & sport; retail, marketing, advertising & PR; and creative arts, culture, entertainment, media & publishing), young people tend to be overrepresented in the sectors that are forecast to see lower employment in the long term. They are similarly heavily under-represented in occupations where we are likely to see the strongest jobs growth in the coming years.

While there is a clustering of young people‘s jobs in cities, these tend to be lower paid jobs in sectors such as accommodation & food, transport & storage, and retail. Meanwhile, the cost of living in cities is high.

Some ex-industrial towns and cities have struggled to adapt to changes in the underlying structure of UK industry (the decline in manufacturing and rise of service occupations) to pivot to new opportunities that create good-quality, well-paid work.

So, as we emerge from the pandemic, we must consider not simply what the impact of the pandemic has been on young people since early in 2020, but how well-equipped they now are to face the future.

Regional disparities in access to jobs

Regional disparities in access to jobs for young people have remained high during the pandemic. While London and the South East have seen the biggest growth in Universal Credit claims, overall levels of youth worklessness remain highest outside of those two regions.

In 34 local authorities, rates of out-of-work Universal Credit receipt among young people are one-and-a-half times the national average. Areas experiencing the highest levels include:

- Areas of high deprivation including Hartlepool (double the national average), Burnley (88% above) and Wolverhampton (85%).

- Coastal towns with a reliance on tourism and hospitality, such as Blackpool, where Universal Credit receipt among young people is 85% higher than the national average, Hastings (81% above the national average), and Thanet (85% above).

Changes in youth unemployment during the pandemic

Looking at Universal Credit (UC) receipt by local authority area gives a granular picture of youth worklessness since early 2020. UC is received by people aged over 18 (and some who are 16-17) who are (i) out of work, and (ii) in-work but on a low income (see footnote 1).

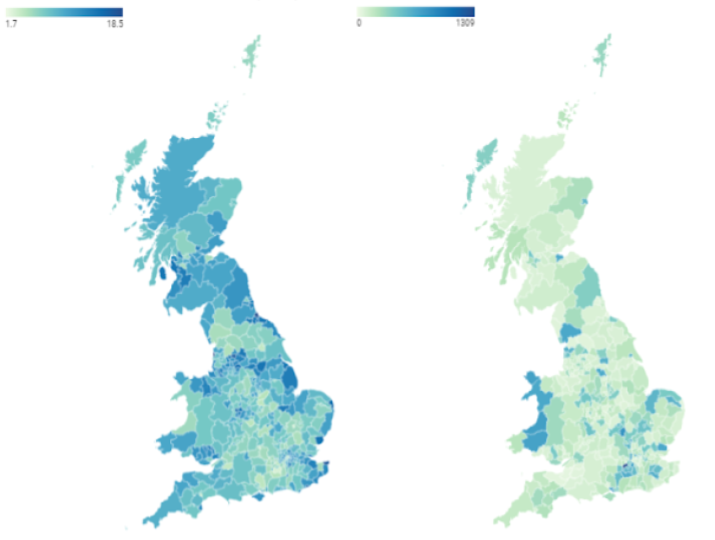

When we look at the growth in those young people out of work and on Universal Credit between January 2020 and April 2021, the increases have been most concentrated in London and the South East:

- London’s high rates of employment in arts & entertainment, the visitor economy and hospitality (among other sectors) mean young people have been hit hard there.

- The 10 local authorities experiencing the highest rises in youth unemployment – all in London and the South East – saw increases of over 150%, albeit from a low base.

However, overall levels of youth worklessness on UC remain highest outside of London and the South East (see Fig.1).

- Coastal towns with a reliance on tourism and hospitality have seen young people lose out significantly during the pandemic.

- Areas with a high percentage of health and public sector employment fared better.

Fig.1: Youth unemployment has increased the most in London and the South East during COVID-19, but levels remain higher in other parts of the country:

Left-hand map: Universal Credit out-of-work claimant rate as a ratio of GB average (Apr 2021)

Right-hand map: growth in long-term (one year-plus) out-of-work UC caseload (Jan 20-Apr 21)

Sources: IPPR analysis of UC data. Both maps produced using Datawrapper

There are also wide variations in youth unemployment between local authorities within regions. For example, in the East of England, the out-of-work rate for those on Universal Credit is more than five times higher in Great Yarmouth than Cambridge.

Regional viewpoints

The regional policy and employer stakeholders interviewed for this research discussed the impact of the pandemic on their areas, and demonstrated how the pandemic has played out differently across the country, as seen in the data. All described how young people had been affected by the pandemic and the lockdowns, including the effects on their mental health.

The stakeholders also described an acceleration of existing inequalities, and highlighted that intersectionality was an important consideration in particularly diverse areas of the country where people from minority ethnic groups, people living in deprived areas, and those with low educational attainment were disproportionately impacted by COVID-19.

They referred to particular sectors where young people predominantly worked (hospitality, leisure & retail sector) that had been shut down. Even affluent areas that had little experience of unemployment were impacted by the shutdown of tourism, arts and culture.

In regions with strong manufacturing bases, the stakeholders believed the combination of Brexit, the pandemic and supply chain issues meant that many employers were struggling.

Concerningly, the research found that long-term benefit receipt (using a measure of 12 months or more) has increased significantly in some parts of the country. Rates have increased over five-fold in some areas of every Great Britain region, with more than 10-fold increases in the East (Luton) and the South East (Milton Keynes).

It should be noted that UC durations can include time spent in work while still claiming benefit – i.e. not all of the individuals will have been continually out of work – and some of these increases are from a small base. Nonetheless, this deserves closer attention in the coming months.

What about underemployment?

As well as considering unemployment, we must consider ‘underemployment’. This refers to those who are not working as much as they would like, and includes those who would either want to work more hours in their current job or are looking for a new job due to wanting to work more hours.

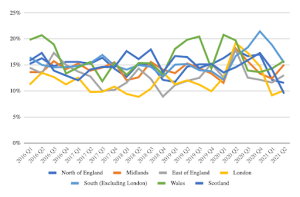

Levels of underemployment among young people rose sharply in the first and second quarters of 2020 (i.e. January to June) but have since returned approximately to pre-pandemic levels. However, these levels are still almost twice as high as those for the general working population.

Underemployment was particularly high in the South of England (excluding London) reaching a peak of 21% in the last quarter of 2020, but has since fallen with the highest underemployment rate now in Wales at 16%, and London and the Midlands not far behind (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Proportion of young people in work who are underemployed, by nation/region:

Source: IPPR analysis of ONS Labour Force Survey

Long-term shifts in the UK’s youth labour market

The wage gap between older and younger workers has grown significantly since the 2008 financial crisis. Young people both with and without a higher education (HE) qualification can expect lifetime earnings that are significantly lower than older workers could when they were the same age. This is particularly an issue for young women (Dabla-Norris et al, 2019).

The outlook for young people’s employment is also worse compared to the outlook for workers aged 30 and over. In addition to being overrepresented in the sectors hit hardest by the pandemic, young people tend to be overrepresented in the sectors which are forecast to see lower employment in the long term.

They are similarly heavily underrepresented in occupations where we are likely to see the strongest jobs growth in the coming years (Learning & Work Institute, 2021). Job polarisation has increased in the UK over the past two decades (Dabla-Norris et al, 2019) and is much more pronounced for young employees than for older age groups.

Long-term regional changes

Both high- and low-skilled jobs have become increasingly concentrated in urban centres, where the cost of living is higher. Meanwhile some ex-industrial towns and cities have struggled to adapt to changes to the underlying structure of UK industry – the decline in manufacturing and rise of service occupations – to pivot to new opportunities that create good-quality, well-paid work (Centre for Cities, 2019).

The shift to remote working during the pandemic is unlikely to significantly alter the clustering of young people’s jobs in cities and large towns, as those sectors with the lowest incidence of home-working over the pandemic period have been accommodation and food, transport and storage, and retail, which are among those with high numbers of young workers. Highly paid, highly qualified workers are the most likely to work from home, and overall, only around 35% of all workers did some work at home in 2020 (Office for National Statistics, 2021).

Most policy interventions in this space are nationally designed and commissioned. However, interviews with regional stakeholders (in particular, those from a Combined Authority area or City Region) highlighted that those areas with devolved responsibility for the Adult Education Budget (which includes young people over 19) have had more flexibility to fund programmes that respond to local needs. Examples include:

- Education Maintenance Allowance-style payments to learners to support them to stay in education;

- funding work experience of learners over the age of 19 in training; and

- ring-fencing funding for careers advice, information and guidance.

It was common for these regional stakeholders to describe how they could support and fund new provision much faster than national government programmes that had been rolled out.

Conclusion

The pandemic has had a dramatic impact on young people’s entry into the labour market and their future employment prospects. Employment rates fell substantially over the period, and there remain nearly a quarter of a million fewer young people in work than at the start of the pandemic, and nearly 200,000 more young people in education and not looking for work than before the crisis began.

While the headline picture of increased participation in education offsetting large falls in employment may appear positive, it disguises significant structural inequalities in the labour market for young people that are at risk of being exacerbated by the crisis. Experience shows it will take active and sustained engagement to reduce these rates. And, while under-employment has largely returned to pre-pandemic levels, there remain stark regional inequalities. Furthermore, young people are still much more likely to be unemployed than other age groups.

This topic snapshot is extracted from the recently published report, A New Deal for the Young: Future-proofing Jobs and Skills Post-pandemic – conducted by the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) and the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), and funded by Youth Futures Foundation and the Blagrave Trust.

Footnote

1 This analysis is restricted to those who are out of work, which includes those claimants who are required to actively seek work (the Searching for Work group) and those claimants with reduced labour market requirements (for example, because of ill health or parenting responsibilities).

It should be noted that Universal Credit (UC) is not a perfect proxy for unemployment – some young people claiming UC who are out of work will not be looking for work (usually due to health or caring), while some of those who are unemployed may not be claiming UC (for example, if they are full-time students).

In addition, the crisis has seen a growth in the number of UC awards with no money in payment, which appears to be due to claims being kept open for longer after people return to work (although we do not know the age breakdowns of claimants with zero awards). Nonetheless, UC receipt is a useful measure for making comparisons between areas and over time at very local levels, where survey data is less reliable.