How to Find Policy Clarity Within the Complex Field of Socio-Economic Inequalities Research

Professor Joanna Chataway and Siobhan Morris

It is a challenging task to choose which areas of socio-economic inequalities research to work on, while ultimately recognising the intersectional, embedded and overlapping complexities of inequities.

There is a need to guard against creating ‘hierarchies’ of inequalities by prioritising action for a certain type of inequity or protected characteristic, for example.

Our aim at IPPO is to adopt an approach that assesses the structural and inter-related inequalities that affect policy responses aimed at tackling just those inequalities.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the current cost-of-living crisis are sharp examples of how societal inequalities in the UK impact and effect policy responses by governments, and they also impress upon us the need to create more sophisticated evidence-based options.

Guiding Principles

Inequality has been written about from many angles. It has been explored with a focus on economic gaps between different sections of the population, to dynamics which exclude people from full participation in a wide variety of mainstream institutions and from the perspective of many other viewpoints as well.

Thomas Picketty’s famous work, Capital in the 21st Century, highlighted the concentration of wealth in the hands of relatively few people in Europe and the US. Picketty’s research is important, not least as it drew attention to the nature of increasing inequality within high- income countries rather than between rich and poor countries. Much has been written about the types and nature of economic inequality after (and indeed before) the publication of Picketty’s book, frequently exploring further the extent of increasing inequality within countries and its characteristics.

Another powerful strand of literature has focused on the relationship between levels of inequality in a society and wellbeing. In The Spirit Level, Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson examined the broader impact of inequality on society. They demonstrated this across 11 different social and health outcomes, showing outcomes are worse in more unequal societies. Michael Marmot has also explored inequalities in relation to health in the UK for some time. The Spirit Level, Marmot’s work, and other notable pieces of analysis were early trailblazers in a now gargantuan literature on the socio-economic and political dynamics associated with inequality.

An important aspect of this work is that much of it asks more specifically, which segments of the population are worst affected and how? In so doing, the conceptual approach incorporates a broader socio-economic and political analytical framing of issues rather than focusing more tightly on economic perspectives.

In phase 1 of IPPO, our focus reflected this wide variety of definitions and approaches to inequality – tending to examine complex dynamics between the impact of COVID-19 and associated policy in relation to socio-economic and political dynamics, rather than in-depth economic analysis. As has now been widely evidenced, the COVID-19 pandemic had unequal impact across different sections of society, and it was in line with IPPO’s mission to deliver rigorous and relevant research to address social policy to explore those inequalities. Thus, in very general terms, our approach followed that broader analytical framing as very briefly sketched above.

However, one of the key issues that arises from adopting that approach is the challenge of narrowing down to identify issues where research synthesis can be undertaken in a useful and rigorous way. This meant tackling the issue of breadth and depth.

Several approaches were key to our approach to doing this. We recognised that useful evidence synthesis could only be achieved where there was a) sufficient and appropriate documented data and evidence to synthesise or b) where there were accessible experts who could provide useful perspectives if documented evidence was lacking. And that work should focus where there was clear, evident policy demand. We carry forward these broad guiding principles to our phase 2 work.

Approach to Work on Socioeconomic Inequalities

In developing principles, rather than detailed implementation plans, we recognise the limitations in relation to implementation and also the importance of enabling flexibility into the policy products we develop so that these can be moulded, relational points of interest explored, and be picked up by policymakers for use in their work at the times and in the contexts that suit their needs – noting in particular that socio-economic inequalities cut across numerous policy areas and don’t ‘fit’ neatly into a particular policy audience.

Over the coming two years, IPPO’s work will build on the perspectives and tools that we developed in phase 1 – working in a way that both reflects, and responds to, policy demand and research supply and the iteration between the two. The adoption of a double helix way of working remains core.

In order to further ground this iterative approach, IPPO has developed a stage-gate approach to use as a heuristic framework to guide decisions about where to devote IPPO resource and efforts. Engagement with policymakers still runs through each stage of work. We have added stage gates which will provide clear points at which demand, supply and relationship factors are considered, and decisions made about whether to progress to the next stage. These stage-gates consist of four processes:

Stage 1: Initial discussions and scoping

This stage includes 1-2-1 conversations with policy stakeholders and a light touch review of policy and academic literature. Assessing the strength of demand for work is an essential component of this stage.

Stage 2: Roundtable discussions

Roundtables will include policy stakeholders, policy researchers, umbrella bodies, and academics. They provide an opportunity to use structured discussion to explore policy evidence need, existing documents and evidence and the scope for synthesis work, a review of people and organisations doing relevant work.

Stage 3: Systems maps of the policy and evidence landscape

Mapping exercises will address the particular policy issue or challenge that emerges from roundtable as a focus for review work. Firstly, mapping the main players, including key policymakers and relevant centres of research expertise. For example, a policy landscape map of efforts to reduce gender-based income gaps would include a description and characterisation of policy actors which include their sector, their primary remit (provision of evidence, lobbying) and their particular interests (wage gaps in private sector, public sector, sectors, etc). Those identified will then be involved in developing systems maps of the reality – how things work – describing patterns of causation around particular issues. Maps aim to describe these visually and can then be linked to evidence – showing which parts of the system are rich in evidence and where it is most lacking.

Stage 4: In-depth Evidence Review or other Review product

In some cases, we will then decide to commission a more in-depth synthesis of evidence – incorporating a search for relevant research, appraisal of the reliability of the research identified, and a synthesis of study findings in order for a decision to be informed by an accurate representation of the state of current knowledge. One example might be choosing between different defined types of intervention for a specific population group.

This process will help us narrow down a set of issues related to socio-economic inequalities that can be examined and addressed, in and across the four nations of the UK.

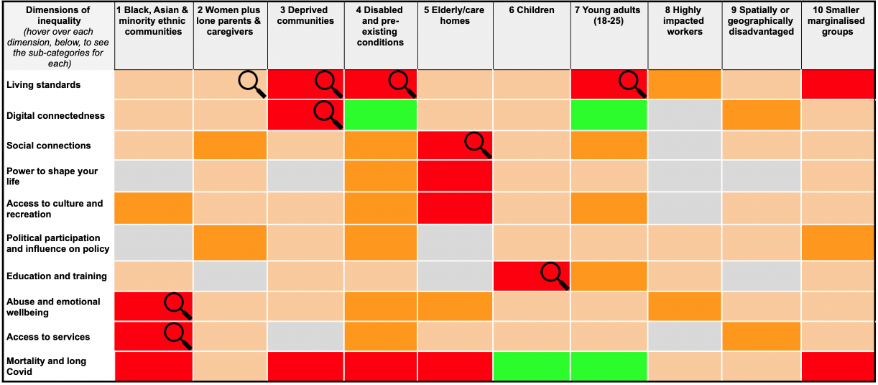

Alongside this, we will utilise a tool developed to map the matrixes of inequalities and specific population groups. Because of the diversity, both of inequality itself and the ways in which COVID-19 impacted on society, one way we conceptualised capturing the breadth and depth, and the ways in which work cut across areas, was to create a matrix (Table 1). This tool is an instrument to help understand the evidence base around inequalities in relation to different sections of society, highlight interlinked intersecting or overlapping aspects of inequalities, and thereby assist decision-making – both in relation to policy and future research agendas.

For example, the matrix allowed us to map in IPPO phase 1 a better understanding of how COVID-19 had amplified some existing inequalities – including hitting many urban ethnic minority communities particularly hard – while in other ways, effects had gone against the grain of recent trends in inequality, as evidenced in the action on street homelessness.

IPPO inequalities matrix (developed in June 2021)

The matrix and submatrices behind each cell indicate where the greatest policy problems may lie (indicated by the colour spectrum ranging from lowest policy demand – grey segments – to the highest – the red segments) and, in the case of cells with a magnifying glass, where more research would be useful.

In phase 2, we will adapt the matrix so that the vertical and horizontal axis relate to specific topics that we are prioritising work on. For example, work on disabilities and hybrid working in a post-covid environment will connect to issues of digital access and social connections. It may also present different challenges in relation to a variety of distinct disabilities or age groups.

It is envisaged that issues on vertical and horizontal axis would emerge from an iteration between research evidence and topic focus as well as facilitating analysis. Another example is poverty stigma – different social groups may well experience stigma in different ways, one type of stigma may impact on the way another form of stigma is experienced.

Next Steps

To date, we have focused efforts on better understanding and assessing policy need on socioeconomic inequalities, with a wide range of stakeholders across the four nations of the UK and with Government stakeholders.

We are also working with a range of partners to identify areas where joint work might be useful. Discussions have identified several fruitful collaborations including on the areas of -local levers for addressing economic inactivity within specific age groups; methodological approaches to adopting an intersectional perspective to policy development and evaluation; synthesising the evidence base on disabilities and hybrid/flexible working practices, including through an international policy scan.

With respect to work on the matrix, our next steps involve testing the steps outlined and iterating on the basis of learning from the practice of using the matrix and refining the conceptual approach.

Our first attempt to use the matrix to inform work will most likely focus on the issue of poverty stigma. A document review and discussions about where the policy issues are most pressing will inform the cells constituting both vertical and horizontal axis, i.e., both the more specific social groups across the horizontal axis and the concrete issues related to the policy issue. In this way, the definition of the problem is rooted in initial analysis. It reflects and sits alongside stages 1-3 of the stage-gate process. As ever, the challenge will be to identify priority topics and products that can drive the greatest impact under the wealth of socio-economic inequalities evidence and policy needs.

If you are interested in re-publishing our work on other platforms, or sharing our work, please email us.