Economics As the Most Politically Influential Field of Knowledge Production

Andrew Plume, Tian Mahony and Joanna Chataway

IPPO is an interdisciplinary initiative established to inform policy with rigorous evidence. It follows therefore that the question of how evidence impacts policy is an important area of interest. This blog adds to reflections from a seminar series that IPPO has organized on the theme of ‘innovations on making evidence useful’ and to other pieces of writing on this website on the topic of how we think about the relationship between evidence and policy. This blog in particular considers whether economics is particularly influential.

More than 90 years ago the British economist Lionel Robbins proposed a highly influential (and not uncontroversial) definition of the subject matter of the field of economics: the allocation of scarce means that have alternative ends (Backhouse & Medema, 2009). From this definition it follows that, if economists are concerned with means, then it is public policy-makers that should be concerned with ends.

However, the extent to which economics is perceived to influence policy differs depending on one’s perspective: Hirschman et al. (2014) asserted that “Every sociologist, anthropologist and political scientist knows that economics is the most politically influential social science.”, but went on to observe that “Every economist, on the other hand, knows that such influence is extraordinarily limited, when it exists at all.”

While it was not possible to enumerate this policy influence in 2014 – much less in Robbins’ time in the 1930s – it has become far more tractable today. Since its launch in 2019, the Overton database of global policy documents has rapidly become a critical resource for quantitative studies of science-policy linkages. Initial characterization of the database by its founder (Szomszor & Adie, 2022) showed that publications in journals classified into the broad subject field ‘Social Science and Humanities’ received the most citations from policy documents overall; when further decomposed into disciplines most citations accrued to journals in ‘Social Sciences’ and ‘Economics’.

A recent news feature in Nature (Chawla, 2024) used Overton data to look instead at the other end of the granularity spectrum, counting policy citations to individual journal publications. Amongst the top ten most-cited papers in policy, eight were published in five different economics journals and included some of the classic contributions to the field stretching back to the 1950s.

Both of the analyses mentioned above revealed that the skewness of policy citations over fields and individual publications follows the same power law distribution that has long been observed for academic citations at all levels of aggregation; that is to say, a few entities attract most of the attention.

A subject-level analysis

Although we recognise some of the limitations of citation analysis – discussed further towards the end of this blog – we were Inspired by these observations and have approached the question of the most policy-influential fields of research in terms of journals, representing a meso-level construct representing the knowledge production of a cohort of expert scholars. We sidestepped the high degree of skewness of policy citations when counted in absolute terms by reframing our main indicator as the proportion of the publications contained in each journal that receive at least one policy citation within a few years after publication. This allows us to see more clearly exactly which scholarly communities are most influential in policy as a proportion of their knowledge production.

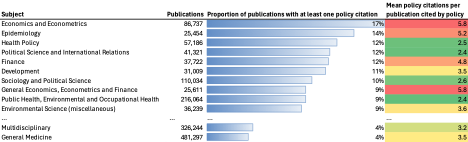

Before examining the journal-level data, we first explored the aggregate view across the 334 fine-grained subjects defined in the Scopus All Science Journal Classification (ASJC). Figure 1 shows the results for the 10 subjects (above an absolute size threshold) with the greatest proportion of publications with at least policy citation. The list is sorted descending on this indicator, which gives a sense of the breadth of policy attention to the publications in each subject. As expected, these subjects are consonant with the greatest public policy challenges of the modern world – human health, international relations, (sustainable) development and the environment.

It is clear that ‘Economics and Econometrics’ has the greatest proportion of publications with at least one policy citation across the 334 ASJC categories, and that the proportion drops sharply over the other 10 subjects listed. (Also included here are two subjects with substantially lower proportions, ‘Multidisciplinary’ and ‘General Medicine’; these subjects contain some of the most prominent journals in the world, which we will examine in more detail below.)

For each subject shown in Figure 1, the mean policy citations per cited publication gives a sense of the intensity of policy attention to such cited publications across these subjects. For this indicator we find that ‘Economics and Econometrics’ and ‘General Economics, Econometrics and Finance’ have similarly high means policy citation rates, suggesting that each policy-cited publication is cited on average around 6 times in different global policy documents and suggesting engagement beyond passing interest.

Figure 2. Journal-level breadth and intensity of policy citations. Overton-indexed policy documents citing Scopus-indexed publications were aggregated at the journal level. For each journal, the count of publications, proportion of these publications with at least policy citation, and the mean policy citations per publication cited by policy (i.e. with at least one policy citation) were calculated. Publications included were articles, reviews and conference papers published in journals in 2019-23, and policy citations were counted in the period 2019-2024. Journals with publication counts in the largest 30% of their subject are shown.

A journal-level view

Turning now to the journal-level view, Figure 2 shows the results for the 10 journals (above a relative size threshold) with the greatest proportion of publications with at least policy citation in each of five selected subjects; again, the list is sorted descending on this indicator to focus on the breadth of policy attention to the publications in each journal. These subjects include the top 3 from Figure 1 as well as ‘Multidisciplinary’ and ‘General Medicine’.

The ‘Economics and Econometrics’ journal list features four of the five journals also highlighted in the Nature news feature (Chawla, 2024) – only Econometrica falls outside the top 10 journals by proportion of publications with at least policy citation. An outstanding 91% of publications in Quarterly Journal of Economics (the oldest professional journal of economics in the English language, edited at Harvard University’s Department of Economics) are cited at least once – and on average more than 25 times – in global public policy documents.

As observed in the subject-level analysis, the proportion of publications with at least one policy citation drops away sharply over the top 10 journals but does so from a higher level and much less sharply in ‘Economics and Econometrics’ than the other subjects shown. This pattern is unparalleled across the other subjects examined. This suggests a great breadth of policy attention across publications within journals and across journals within this subject; and the relatively high mean policy citations per cited publication demonstrates a strong intensity of that attention too.

In ‘Epidemiology’, one of the fields thrust to the fore during the COVID-19 pandemic, 77% of the publications in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report were cited at least once in public policy in a period largely covering the emergence and spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The journal is published by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and is often called “the voice of the CDC”. In ‘Health Policy’ several of the top 10 journals are health economics titles, including the top-ranked Journal of Heath Economics. In ‘General Medicine’, the top-ranked title (with a proportion of publications with at least one policy citation much greater than well-known medical titles such as The Lancet, New England Journal of Medicine, BMJ and JAMA) is the Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. This is the flagship health periodical of the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean and publishes in Arabic, English, or French.

Finally, despite including some of the best-known scientific and scholarly journals in the world, the top 10 ‘Multidisciplinary’ journals show a relatively low breadth of policy attention across their publications. Indeed, the single article from Nature that was included in the aforementioned Nature news feature included several co-authors affiliated with economics departments or institutes.

Through this analysis of a relatively new database of global policy documents linked to the journal publications they cite, we have demonstrated that economics is not only the most politically influential social science, it is the most politically influential field of knowledge production of all. As such, it follows from Robbins’ definition of economics that economists must continue to examine scarce means and provide informed views for policymakers on their alternative uses.

What do citations in policy documents mean?

The title of this article refers to the relationship between a knowledge production subject area – economics – and policy influence. The analysis above is based on an assumption: that citation of academic work in policy documents indicates policy influence. We need to note however the limitations on the indicator that we are using. The influence of academic work on policy is not straightforward. A blog by Overton (Overton, 2023) notes that having an impact on policy “may involve different projects, interlocutors and back and forth interactions over years and this won’t always be clear in citation data. […] So we know that citations in policy documents are just one narrow – if important – measure in the policy engagement story. Though citations are generally accepted as the currency of scholarly influence (for better or worse), policy influence is undoubtedly more complex.”

In a piece of work carried out in 2023, Basil Mahfouz (Elsevier, 2023) examined factors underpinning the extent to which academic work had an influence on policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Amongst those factors it is worth highlighting the importance of time – older academic publications are more likely to be cited than more recent work. This of course brings into question the degree to which new and cutting-edge research influences policy rather than research which has become embedded in narratives which make their truths more acceptable and easier to digest. We are not clear what factors increase the likelihood of the acceptability of one set of ideas becoming policy-relevant over another.

To add to this, a finding from Mafouz’s work is that there is a weak link between research excellence and citations to publications from policy documents. An inferred observation might be that during the pandemic and perhaps in other contexts, policymakers may have relied on existing networks of trusted experts rather than new academic work. It is possible that policymakers may use academic contributions as a security blanket or cover whilst drawing on familiar sources rather than novel research to guide policy.

None of this in itself calls into question the influence of economics on policy as opposed to other social and natural sciences, as much as the type of research and researcher within economics that is likely to have the impact. Those who, over time, invest in relationships with policymakers are more likely to reap rewards in relation to actual impact of academic work. There is now a body of literature of course which suggests this.

Another question which could follow the analysis in this blog is whether the use of insights from economics – with or without research from other fields – actually improves policy. That seems like an important question to ask and one which would take some creativity to answer!

Conflict of interest statement

Andrew Plume and Tian Mahony work at Elsevier, which produces the Scopus database and is the publisher of many of the journals mentioned in this analysis.

References

- Backhouse, R.E. & Medema, S.G. (2009), Defining economics: The long road to acceptance of the Robbins definition. Economica, 76, 805-820. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00789.x

- Hirschman, D. & Berman, E.P. (2014) Do economists make policies? On the political effects of economics. Socio-Economic Review, 12(4), 779–811. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwu017

- Chawla, D.S. (2024) Revealed: the ten research papers that policy documents cite most. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00660-1

- Szomszor, M. & Adie, E. (2022) Overton: A bibliometric database of policy document citations. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.07643

- Overton (2023) Three things we’ve learned about policy citations. https://blog.overton.io/three-things-weve-learned-about-policy-citations

- Elsevier (2023). What determines whether a research article is cited in policy? https://www.elsevier.com/en-gb/connect/what-determines-whether-a-research-article-is-cited-in-policy