All Change, or Loose Change? Tax Powers and Wales’ Constitutional Evolution

This blog is part of an IPPO series looking at how policymaking across England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland has been shaped by devolution over the past 25 years.

Ed Gareth Poole

The quarter century since devolution has served up plenty of political drama and big-ticket constitutional change. But although Scotland’s 2014 independence referendum and the stop-start travails of Northern Ireland powersharing have attracted the most attention, it is in Wales that the initial settlement has changed most radically.

Slowly but surely, by means of at least five changes to its devolution dispensation, Wales has accrued a set of powers that would astound those first sixty members elected to the Assembly in May 1999.

These changes to Wales’ devolution settlement have come thick and fast. The original (and much-criticised) local government-style ‘body corporate’ model was replaced by a legally separate legislature and executive by 2006. By 2011, a referendum to grant primary legislative powers to the Assembly had been rewarded with a 63%-37% mandate for devolution – one which helped underpin far greater confidence than had the wafer-thin margin in 1997. By 2017, the ‘conferred powers’ model of primary lawmaking had been replaced by a broader ‘reserved powers’ model on Scotland and Northern Ireland lines. And, of course, Brexit – voted in by a narrow majority against the entreaties of the Welsh political class – upended Wales’ strategy of working laterally with member states and historic regions across Europe and replaced it with the far more fractious dealings of an intra-UK internal market.

The story of fiscal devolution exemplifies a pattern of cross-party and expert-working in Wales in which painstaking work by commissions can (eventually) deliver pro-devolution reforms – even under Conservative-led governments.

The seeds of change were sown less than a decade after devolution, when the 2007-11 Labour-Plaid Cymru coalition government – itself inconceivable in a Scottish context – established an expert commission to consider Wales’ funding under economist Gerry Holtham. As a body set up at the devolved level it was unable to deliver immediate policy change at Westminster. But it was so well respected across the political spectrum that it set the train in motion for fiscal devolution during the 2010s – riding the slipstream of the Calman Commission that met in Scotland between 2007 and 2009.

Thanks to the insistence of Welsh Liberal Democrats in government formation negotiations after the 2010 general election, the incoming coalition government swiftly established a UK commission to take up the reins from Holtham. Led by Paul Silk, a former clerk at both the House of Commons and the Assembly, this commission exemplified the painstaking work of cross-party consensus building that (until Brexit) had been a hallmark of Wales’ gradual, elite-level embedding of major settlement changes over time.

Silk largely accepted the Calman Commission’s roadmap for Scottish fiscal powers via a set of limited recommendations that were passed into law by the Wales Act 2014. These involved the wholesale devolution of stamp duty and landfill tax and the devolution to Wales of 10 pence of each of the three bands of income tax (20p/40p/45p). But the big-ticket item – income tax – would not be triggered until it was supported by Welsh voters in (yet another) national referendum. The ink was barely dry on this Act when the entire political class belatedly accepted that such a restriction would keep the proposal buried forever. The 2017 Wales Act therefore swept away the referendum requirement and directed that close to half of Wales’ income tax receipts should be devolved to Wales starting in April 2019.

Recall that unlike the pre-Union Scottish Parliament and the post-partition Parliament of Northern Ireland, there had never been a Welsh tax-raising parliamentary body with undisputed control over all of the territory of modern Wales. The 2014 and 2017 Acts therefore represent a real watershed in Welsh history, giving the Welsh government the authority to levy taxes and manage its borrowing to a greater extent than any other Welsh administration in history.

Given the relatively small impact of decisions for Wales in the context of the UK’s fiscal envelope, negotiations with the Treasury tend to be quicker for Wales than for Scotland. The Welsh Fiscal Framework – the agreement setting the rules by which billions of pounds in taxes would be devolved to Wales – was concluded in just two months. In return for accepting a less generous formula for devolving income tax than had Scotland, the Welsh government negotiated a new ‘needs-based’ multiplier to the Barnett Formula that would correct some of the worst elements of the formula with respect to Wales’s spending by setting a funding floor, below which Wales’ per capita levels of funding could no longer converge to that of England. Unlike in Scotland, Wales’ agreement has had an enormously positive budgetary impact – it boosts the Welsh budget by approximately £300 million per year relative to the previous system, equivalent to a 1p rise in each of the basic, higher and additional rates of Welsh income tax.

The Limits of Empowerment

Although fiscal powers were intended to increase the accountability of the Welsh government, allowing it to better tailor fiscal policies to local needs and preferences, since 2019 the Welsh government has generally followed the fiscal path set by Westminster. Calls by Plaid Cymru for Labour to use its income tax powers have so far fallen on deaf ears. Instead, and again unlike in Scotland, Welsh Labour has made up for austerity budget settlements by authorising local authorities to continue to raise council tax by inflation-busting levels.

But although its reluctance to raise revenue has forced Welsh ministers to justify resulting cuts to large numbers of public and voluntary sector organisations, these decisions are all taken in the context of the impending UK general election – and a campaign that will inevitably draw comparisons between a Conservative-led UK government and the record of Wales’ Labour-led administration.

Fiscal devolution is therefore historic yet entirely unrevolutionary, at least in policy-making terms. The Welsh Government has tended to continue its strategy of projecting blame for squeezed budgets onto Westminster, and thanks to the NHS’s Pac-Man-like ability to consume an ever increasing share of public expenditure, efforts to align budgets with strategic priorities have featured only at the margins. And while tax devolution aimed to shift Welsh budgeting from a reactive to proactive system of longer-term strategic planning; this was not to be. The feast-and-famine rollercoaster of public expenditure since the 2008 financial crash continues to scupper medium-term budgeting and long-term capital investment planning everywhere in the UK.

“A Process and Not an Event”

Perhaps though, the impact of tax devolution is not in the realm of policy making and budgeting, but rather as another foundation stone in the ongoing process of nation-building and identity shaping in modern Wales. Might tax powers might be less important for what they do than the basic fact they exist in the first place? After all, tax powers are fundamental to emerging polities – as Lord North’s government was painfully reminded by American colonists in the late eighteenth century.

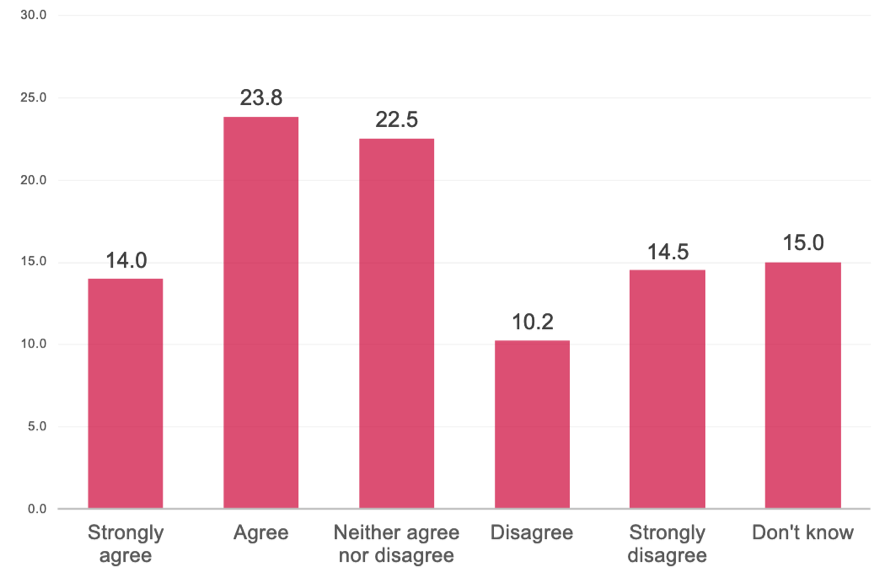

The 2021 Welsh Election Study contains evidence for this view. Despite low public awareness and despite being a policy pursued and implemented by Conservative-led governments at the UK level, not only do a majority of voters favour devolved income tax but those most in favour are those who most favour devolution of any kind, namely Welsh Labour and Plaid Cymru voters. Just as with any other competence that has been accumulated since devolution, tax powers have been subsumed into the bundle of powers and rights that represent Wales’ distinctiveness within the United Kingdom.

Percentage of Welsh voters agreeing with devolved income tax

Tax devolution, therefore, might not be seen in the context of the ‘fiscal federalism’ literature of old, but rather as a staging post for the continuing contestations of modern Welsh nationhood.

This post is part of a series of posts looking at how policymaking has been shaped by devolution during the past 25 years.