What Policy Interventions Are Needed to Reduce Economic Inactivity for People with Poor Health and Older People?

Amy Ramsay

Economic inactivity among working-age adults has remained stubbornly high since the Covid pandemic, resulting in lost taxes, reduced consumer spending, and increased benefit payments.

The UK is now the only G7 country whose employment rate is not back to pre-pandemic levels.

Against the backdrop of a UK labour shortage and a reported £22bn fiscal black hole, there is an urgent need to address economic inactivity. The most likely groups not to be in work or looking for a job are those with long-term health conditions and older people.

However, these groups are not discrete, as more than half of all people out of work due to health conditions are between 50-64.

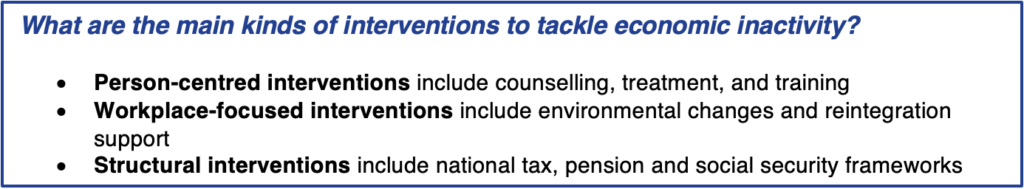

In its latest rapid evidence review, IPPO looked at policy interventions that could reduce economic inactivity across the following two areas:

- evaluated the effectiveness of economic inactivity interventions for people with poor health and disability.

- mapped interventions for older people, the second most likely group to be economically inactive.

Summary of Findings

Our research identified a series of policy interventions that could better support those with physical and mental health problems and learning disabilities.

- Expand Individual Placement Support (IPS) – shown to be particularly effective for young people with mental health conditions and those with severe mental health problems

- Increase use of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) as an effective intervention to support return to work

- Make changes to workplace and equipment, work structures and organisation design to reduce ‘return to work’ time and sickness absence days. Evidence suggests these changes are particularly impactful for people with musculoskeletal disorders

- Increase training opportunities. Training such as Computer-Assisted Cognitive Remediation positively impacts employment, days in work, and earnings

However, it was not possible to identify evidence on the efficacy of interventions to support older people to remain in or get back to work after sick leave or breaks from employment. We suggest therefore that policymakers need to concentrate on:

- Trials combining different types of interventions, to better understand a more holistic approach

- How an intervention contributes to a chain of results

- The effectiveness of interventions for people from socially excluded or underrepresented groups

The remainder of this briefing focuses on the challenge of supporting older people to reduce economic inactivity among this group.

Economic Recovery Relies on Supporting Older People

Older people are the most likely group in the UK to be economically inactive. Supporting older people to remain in or return to work is crucial if the Government is to meet its ambitious target employment rate of 80% as part of its Get Britain Working package.

The financial benefit of closing the employment gap between older and younger workers is estimated to be £1.6 billion a year. This amount is likely to grow, with the number of people between 65-79 predicted to increase by almost a third in the next 40 years. Finding effective ways to support older people (with or without health conditions), to remain in or return to work is a challenge that will only become more important.

What is causing economic inactivity among older people?

We know that increased inactivity is caused by a range of factors, including worsening health, caring responsibilities and ageist attitudes towards older workers.

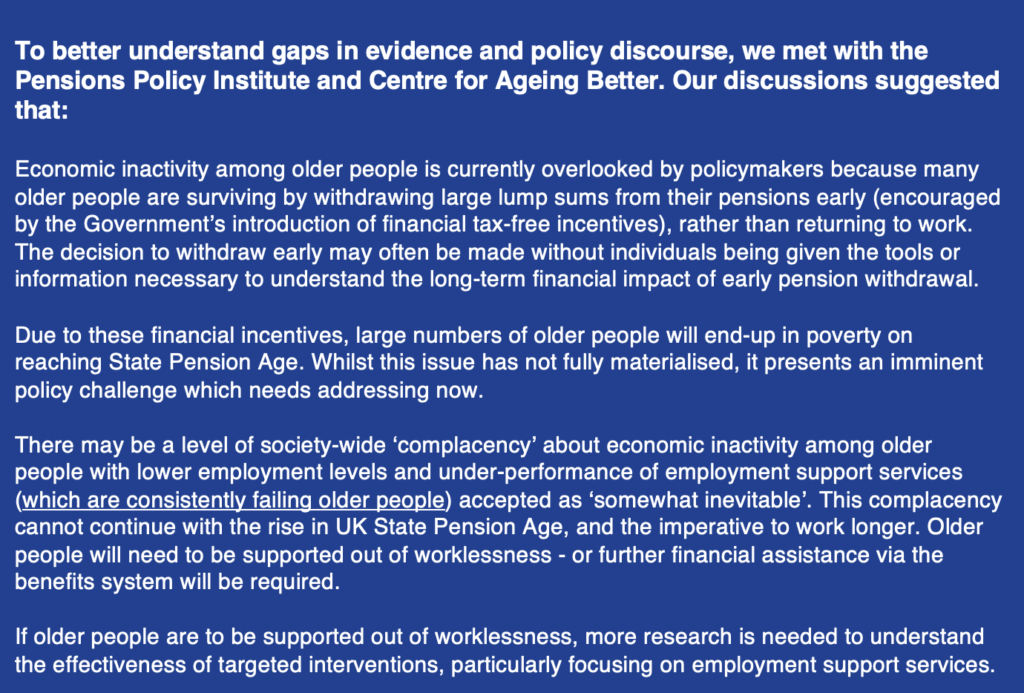

We looked at interventions specifically aimed at supporting older people to stay in or return to work. However, there is an evidence gap around what works to bring older people back into the workforce.

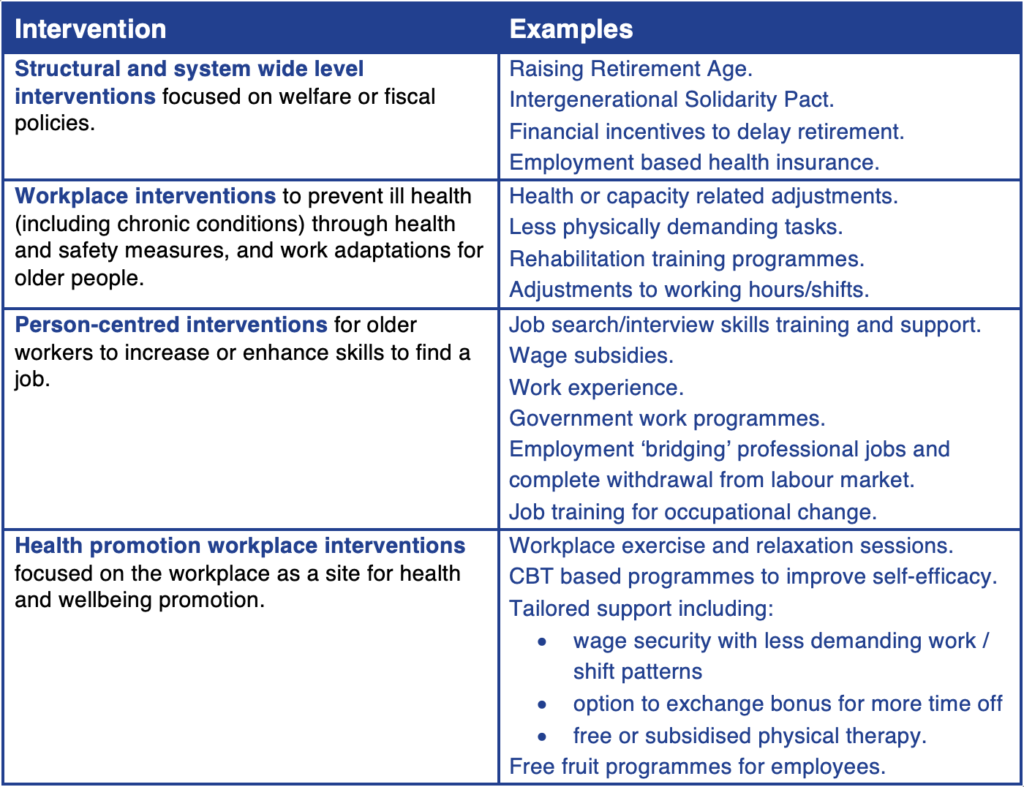

Examples of Current International Policy Interventions

The Evidence Gap

We do not have sufficient evidence of the effectiveness of interventions (both in the UK and internationally) aimed at supporting older people to stay in or return to work. Importantly, we don’t understand why some interventions might work for some older people, and not others. Nor do we know enough about the circumstances or chain of events required for an intervention to be effective. There is also a lack of evidence on which interventions work to support people returning to work after longer absences or to support older people from underrepresented and marginalised groups. Finally, we don’t yet know how interventions aimed at supporting older people to stay in or return to work interact with structural and systems-level interventions, such as pensions policy, financial incentives or anti-discrimination legislation.

With tackling economic inactivity a key mission outlined in the recent Budget, and an investment of £240 million promised to accelerate the rollout of local services aimed at driving down inactivity, it’s crucial that the needs of older people, with and without health conditions, remain front and centre.

By focusing on older people (with and without health conditions), we can help foster greater financial security and improved health for the UK’s rapidly ageing population, creating supportive and productive multi-generational workplaces and a healthier population.