Population Ageing and Decline: What Policies Might Mitigate the Downsides?

Amanda-Hill Dixon

Along with the rest of the UK, Wales’s population is ageing and there is a real chance of population decline, posing significant risks to economic wellbeing. Policy-makers can learn from international evidence on boosting fertility, retaining population and attracting inward migrants.

It is projected that there will be around 77,000 more deaths than births in Wales between mid-2020 and mid-2030. Almost all of the growth in the Welsh population will be among the over 65-year-olds, with the number of under-18s predicted to start falling from the mid-2020s.

This poses significant risks to the economic and fiscal wellbeing of Wales, including a possible relative reduction in the funding that Wales receives from the UK Treasury. So, what can policy-makers in Wales and elsewhere do to slow or reverse the trends of population ageing and decline?

The Wales Centre for Public Policy has published a review of international evidence on these challenges and policies to address them.

There is strong evidence to suggest that ‘pro-family’ policies, such as more generous childcare and parental leave, are associated with increased fertility. The impact of long-term environmental factors on fertility also requires attention. But policies to boost fertility will not make a positive difference to tax receipts for a generation or more.

As such, shorter-term policies that aim to retain the existing population, to attract inward migrants and to boost workforce participation and productivity are worth considering, although there is weaker evidence about ‘what works’ in these areas.

What works to boost fertility?

There is now a gap in Europe between the average number of children that people want and the number that they are able to have. For example, on average across the population, women in the UK have 0.3 fewer children than the number that they say they want.

Policies to boost fertility should seek to address this gap by enabling people to have their preferred number of children.

Socio-economic interventions

For many people, it is socio-economic factors that determine whether they try to have children and, if so, how many. Key policies include parental leave, childcare and financial incentives.

Overall, there is strong evidence that expanded and generous parental leave increases fertility. Large increases in parental leave have repeatedly been shown to have positive impacts on fertility. For example, an Austrian reform that doubled the leave period from 12 months to 24 months led to a 5.7% higher likelihood of families having another birth. Other studies, including in Quebec and the United States, support this finding.

While maternity leave is relatively generous in the UK, in terms of longevity, compared with other OECD countries, payment rates are lowest in the UK and Ireland. Here, only one-third of gross average earning are replaced by maternity benefits.

As such, there is potential to increase fertility by enhancing the generosity of parental leave payments in Wales and the UK more broadly.

The availability and affordability of childcare are two of the key factors determining how easy it is for women to combine family and work. Evidence from across advanced countries shows that public spending on early childhood education and care is closely related to both fertility rates and women’s employment.

In Germany, the staggered local implementation of a new federal childcare policy ensuring that any child under the age of three has access to free childcare slots finds ‘consistent and robust evidence of a substantial positive effect of public childcare expansion on fertility’. This study shows that a 10% increase in childcare coverage led to an increase in the number of births per 1,000 women of 1.2.

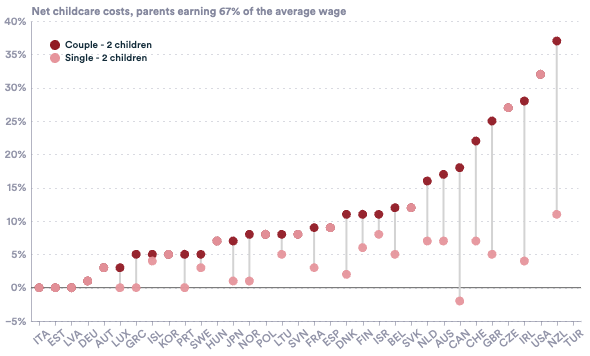

In the UK, childcare costs are some of the highest among OECD countries (see Figure 1). This evidence and the situation in Wales strongly suggest that there is scope for the Welsh and UK governments to invest more heavily in early childhood education and care as a way of making the prospect of having children more financially feasible, and thereby potentially boosting fertility.

Evidence shows that affordable high-quality early childhood education and care provision brings additional positive outcomes, such as reduced poverty and enhanced childhood development.

Some countries and sub-national governments have opted for cash transfers from the state to parents, such as ‘baby bonuses’, to encourage fertility. Other countries have offered tax deductions for people having children, with some offering greater tax deductions for every extra child born in a family.

But the effects of these incentives, especially the cash payments, tend to affect when people choose to have children rather than how many they have. The effects on population fertility are therefore often transitory rather than long-term.

This suggests that pro-family policies that support child and parental wellbeing in the longer term, such as childcare, are likely to be more effective than pro-natal policies, which aim simply to provide incentives for more births.

Medical and health interventions

There is a range of medical and health interventions that can be provided for those who would like to have children but are currently unable to do so because of fertility problems. The most common medical intervention is assisted reproductive technology (ART) – including in-vitro fertilisation (IVF), which represents 99% of ART – and other procedures working with eggs or embryos.

There have been a number of initiatives in different countries or at sub-national levels, where ART has been partly or fully publicly funded. Two Canadian provinces – Ontario and Quebec – have been offering publicly funded ART since the mid-2010s.

In Ontario, anyone under the age of 43, regardless of gender, sexual orientation or family situation, is eligible for one cycle of IVF, with a maximum of 5,000 cycles being funded per year across the province. An expert panel convened by the Ontario government stressed that publicly funded IVF would address the main barrier to IVF access, which is its cost.

Since the policy was implemented, the use of IVF by women between the ages of 40 and 43 has doubled, with a cumulative live birth rate (meaning births resulting from fresh and frozen embryo transfer) of over 10%.

In Quebec, the overall birth rate decreased during the funded period, arguably as a result of people deciding to delay having children because of improved access to IVF.

As such, while access to ART is likely to increase the fertility of individuals who are struggling to conceive naturally, public expansion of such support may not lead to an increase in the national birth rate if women decide to delay having children. Nevertheless, there are clearly other good reasons – such as supporting the right to reproduction – for supporting access to ART.

Long-term environmental factors

There is growing evidence globally that male sperm counts are declining rapidly. A recent meta-analysis of sperm counts from 1973 to 2018 finds a 51.5% average decrease.

While the causes of this decline are not fully understood, researchers are increasingly pointing towards environmental factors, including pollutants and ‘forever chemicals’ – per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), which are toxic and do not break down in our bodies or the environment.

Governments may therefore wish to consider policies to reduce their population’s exposure to air pollution and forever chemicals as a way of protecting the long-term reproductive health of the population and ultimately as a way of tackling population decline.

This approach could achieve longer-term savings due to improved health, fertility and reduced demand for health services in the future, particularly as PFAS have been linked to cancer, immune system harm and other diseases.

Nevertheless, however effective, any policy to boost fertility will not affect tax receipts for at least a generation. As such, policy-makers must look to shorter-term policies to boost the size of the working age population. The evidence for such approaches is weaker, but there are useful international examples on which to draw.

What works to retain people?

International policies to encourage people to stay in an area are based on a recognition of the factors that influence decisions about whether to remain or leave, such as employment, housing and transport. Many of the factors that determine retention –though not all – are the same factors that determine people’s decision to migrate to another area.

Graduates are a key group on which to focus retention efforts because they are mostly highly skilled. They are also often young, of prime employment age and have the potential to contribute to the regional economy and its productivity over the long term.

Opportunities for progression (the ‘escalator effect’) appear to determine graduate decisions on whether to leave or remain in their city of study. Other key factors include a reliable and efficient transport system, an affordable housing market with a variety of available properties, and a planning system that can respond to changing employment patterns and residential demands.

As well as concentrating on certain age groups, particular geographies can be the focus of retention efforts.

Rural regions are often at greater risk of depopulation. As a result, retaining people in rural areas, especially young people and working people, is key to maintaining a balance in age groups and economically active/non-active people.

A particular factor for Wales – as for Italy, Japan and Scotland – is that when people leave rural areas, they often also leave the country. For example, a Welsh survey finds that while 75% of young people enjoy living in rural Wales, 40% believe that they will have to leave Wales within the next five years, even though they would prefer to stay.

When asked about what policy changes would make them stay, the young people responded similarly to the factors shown to support the retention of graduates. They emphasised access to more appropriate jobs, followed by better transport connections, better paid jobs, more entertainment and leisure, more affordable housing and improved broadband.

In terms of what kinds of jobs, housing and transport are needed in a particular locale, many of the policies reviewed stress the need for a holistic and localised approach to the challenge of rural depopulation.

For example, research on policies implemented by different European countries to address rural depopulation finds that all successful initiatives were built on ‘a realistic analysis of the existing situation’.

What works to attract inward migrants?

Attracting people via inward migration is another way in which governments can try to boost the size of their working age populations, and to shift their skills composition.

Between April 2011 and March 2021, the only reason that the population of Wales grew was due to positive net migration of around 55,000 usual residents, from within and beyond the UK.

In recent years, the rate of international inward migration to England has been higher than the rate for Wales. Although immigration policy is a function of the UK government, the Welsh government plays an important role in the delivery of immigration policy and the shaping of places, communities and other public services, in ways that can affect whether people choose to move to Wales and for how long.

Some countries and regions have been particularly successful in attracting people to live and work. Since 2020, a number of countries, including Australia, Italy and the United States, have put in place financial incentives for individuals and businesses to relocate to depopulated (often rural) areas.

Scotland has also deployed financial incentives, alongside empty properties and ‘crofting’ – a form of small-scale land tenure particular to the Scottish Highlands and islands. These policies have attracted a net inflow of about 20,000 mainly young migrants per year from the rest of the UK over the last 20 years.

There is also a role for cultural policies to attract migrants. In Denmark, the community of Friederikshavn was revitalised by the establishment of the ‘experience economy,’ with offerings such as festivals, cultural events and tourist attractions. This was followed by a settlement service that offered housing and job opportunities to people moving to the area, including language-learning opportunities for non-naturalised citizens.

What are the key takeaways for policy-makers?

Population ageing and decline are increasing concerns among policy-makers in Wales, the rest of the UK and many other advanced countries.

A range of strategies can be deployed to boost the size of the working age population. In the long term, expanded pro-family policies are needed to make having children affordable and viable as part of a dual-earner family model. Long-term environmental factors also need to be addressed.

In the shorter run, governments can consider a range of policies to retain residents and attract inward migrants, particularly by ensuring the availability of good jobs, affordable and good quality housing and decent transport. There is also a need for policies that aim to boost economic activity.

Finally, as well as seeking to mitigate population ageing and decline, there is a potentially more urgent role for governments in effectively managing population change, for example, by ensuring that services are adapted and able to meet the needs of an ageing population while protecting services and provision for children and young people.

Where can I find out more?

- International approaches to population ageing and decline: Report by the Wales Centre for Public Policy.

- Profile of the older population living in England and Wales in 2021 and changes since 2011: Report from the 2021 census, Office for National Statistics (ONS)

- Births in England and Wales, 2022: Report from the 2021 census, ONS.

- Understanding Wales’ ageing population: key statistics: Report from the Older People’s Commissioner for Wales.

- Impact of migration on UK population growth: Report by the Migration Observatory.

Who are experts on this question?

- James Banks

- Amanda Hill-Dixon

- Andrew Scott

- Graeme Roy

This post was reproduced with permission from the Economics Observatory.