International Expertise in National Science Advisory Systems

Jean-Christophe Mauduit

With the rise of increasingly complex global challenges, from climate change and public health crises to technological disruptions, having access to relevant expertise and considering the best available knowledge to inform policymaking is crucial.

This not only requires a solid science policy interface and a well-established science advisory system, but also strong links to the international realm through science diplomacy interfaces. Indeed, important expertise and knowledge may be beyond the domestic realm.

The COVID-19 crisis highlighted differences in how different countries’ science advisory systems sourced international knowledge and expertise, and how it informed domestic policies. In the UK, a 2022 report of Parliament observed that international evidence and expertise was not effectively utilised in policymaking during the pandemic. This observation underscores the difficulty in ensuring the best access possible to international evidence, and in incorporating it alongside domestic ones into actionable policy measures.

Understanding how science advice operates in different national contexts, and how countries are sourcing international expertise could therefore provide some helpful insights for the UK system. This is what a team of six UCL STEaPP Master’s students looked into, under the supervision of an IPPO team member, an INGSA member and a STEaPP professor. Over the course of 6 months, they led a comprehensive literature review, interviewed a dozen experts in science advice and science diplomacy, and delved into three case studies ranging from low, middle to high income countries (UK, Argentina and India). Their work resulted in a 60-page report detailing the findings and offering recommendations to civil servants and science advice & diplomacy professionals.

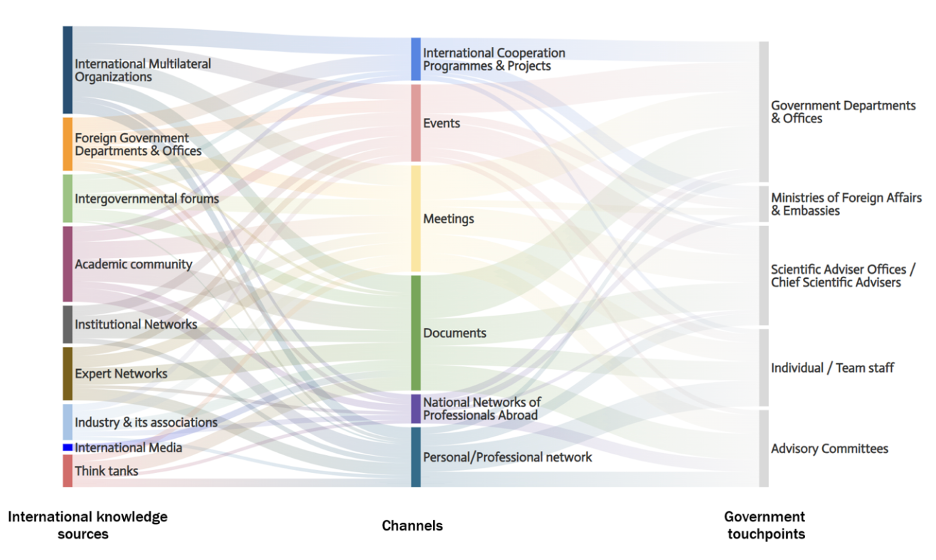

Here ‘international knowledge sources’ include, among others, experts from international multilateral organisations, foreign government departments and offices, expert networks or think tanks. ‘Channels’ can be international reports or publications but also bilateral or multilateral meetings, personal/professional network or national networks of professionals living abroad. ‘Government touchpoints’ can include advisory committees, Embassies, scientific advisers or civil servants working within governmental institutions.

When considering the pathways along which the information travels from the international to the domestic realm, there are three fundamental components to consider: (1) the international sources of knowledge and expertise themselves, (2) the channels that facilitate the flow of knowledge across borders and (3) the government touchpoints that enable its integration into the domestic science advisory system.

By analysing the examples detailed in the literature and the ones highlighted by the interviewees, the researchers carefully reconstructed the multiple pathways through which international evidence travels. As shown in the Sankey diagram below, these three components together form a complex, non-linear process. Multiple government touchpoints may reach out to multiple international knowledge sources through multiple channels, forming an intricate array of pathways. These pathways may also vary across policy issues. Nonetheless, behind this complexity lay many interesting learning points.

Multilateral organisations and the international academic community are the most significant sources of knowledge and expertise. Gathering documents, holding meetings and attending events stand as the more recurrent channels to connect the universe of existing actors in both ends of the spectrum. Government departments and offices (and when this structure exists, the Science Advice Office or a Chief Scientific Advisor) along with advisory committees, are well-positioned as visible, internationally connected contact points with decision makers.

Notable variations exist across countries and contexts. For example, some deliberately appoint international experts within the domestic structures themselves, such as advisory committees, where others rely nearly exclusively on domestic ones. International expertise and knowledge are more often sought during situations of emergencies and crises than in normal times.

In addition, the study revealed that these various pathways are dependent on a multitude of interconnected factors. Among these factors, three were identified as having a significant influence in the shaping and efficiency of the pathways, and how they inform policy formulation: (1) the particular public policy domain of interest, (2) the political (and geopolitical) landscape the science advice system operates in, and (3) the agency of staff populating the bureaucracy. The links between the three are important to note: the ideology of a government and its geopolitical alignment with certain countries may influence where (if at all) international expertise is sought for a particular policy domain.

While the first two factors are context-dependent, the third one seems to be a common issue. Indeed, there is an overreliance on personal networks cultivated by science advisory personnel and civil servants. This dependency, though offering flexibility and allowing for timely communications during crises, renders these pathways vulnerable to the individuals in position. There is therefore a lack of institutionalisation of the pathways and no methodical approach for integrating international evidence into the policymaking process. This is particularly problematic as it may not incentivise civil servants to actively seek this expertise beyond the national realm but also restrict their ability to conduct quality assurance of the evidence base gathered – both ensuring its completeness and protecting it from unwanted foreign influence. The next steps in the research will involve two roundtables with selected professionals who have deep knowledge of the science advice system in their respective countries.

The first roundtable will take place at the May 2024 INGSA conference in Kigali, Rwanda. Participants coming from many different country settings will give a glimpse into a wide array of science advice systems and how they incorporate international expertise and evidence into their domestic policymaking. Their contributions will contribute to the development of ideas to improve pathways and quality assurance processes. In the fall of 2024, a second roundtable will take place in London with UK stakeholders to understand how these could be incorporated into the national science advice system. It will also explore the potential roadblocks in getting this evidence to bear on policy-making, and what factors may be preventing it.