How should we address the many social inequalities amplified by COVID-19? The case for social multipliers

IPPO Co-investigator Geoff Mulgan offers a policy-focused response to our recent Action On Inequalities event, which saw several hundred policymakers, researchers and practitioners from across the UK brainstorm how to tackle the many inequalities COVID-19 has exacerbated

Introduction

No one is in any doubt that COVID-19 has had remarkably uneven and unequal effects. Its most direct effects in terms of illness and death were overwhelmingly concentrated on the elderly, disabled people and the already sick, as well as certain professions including nurses, doctors and taxi drivers.

The pandemic’s second-order effects hit the young disproportionately through the shutdown of schools and a striking loss of jobs (furlough notwithstanding). Working women were more adversely affected than men because of their greater burdens of care and home schooling and rises in domestic violence, and there were sharp differences between the experiences of white-collar workers with large homes and gardens and manual workers without them.

Since the beginning of 2021, the International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO) has been gathering evidence on many of these uneven patterns and also looking at their remedies – from the mental health challenges faced by schoolchildren and care home residents, to the opportunities for lasting change to address homelessness in the wake of COVID-19, and what to do about labour market shocks as part of the recovery process.

A framework for thinking about inequalities

In mid-June, we brought together several hundred policymakers, researchers and practitioners from all parts of the UK to discuss how best to address the many inequalities that COVID-19 has highlighted and exacerbated in each nation.

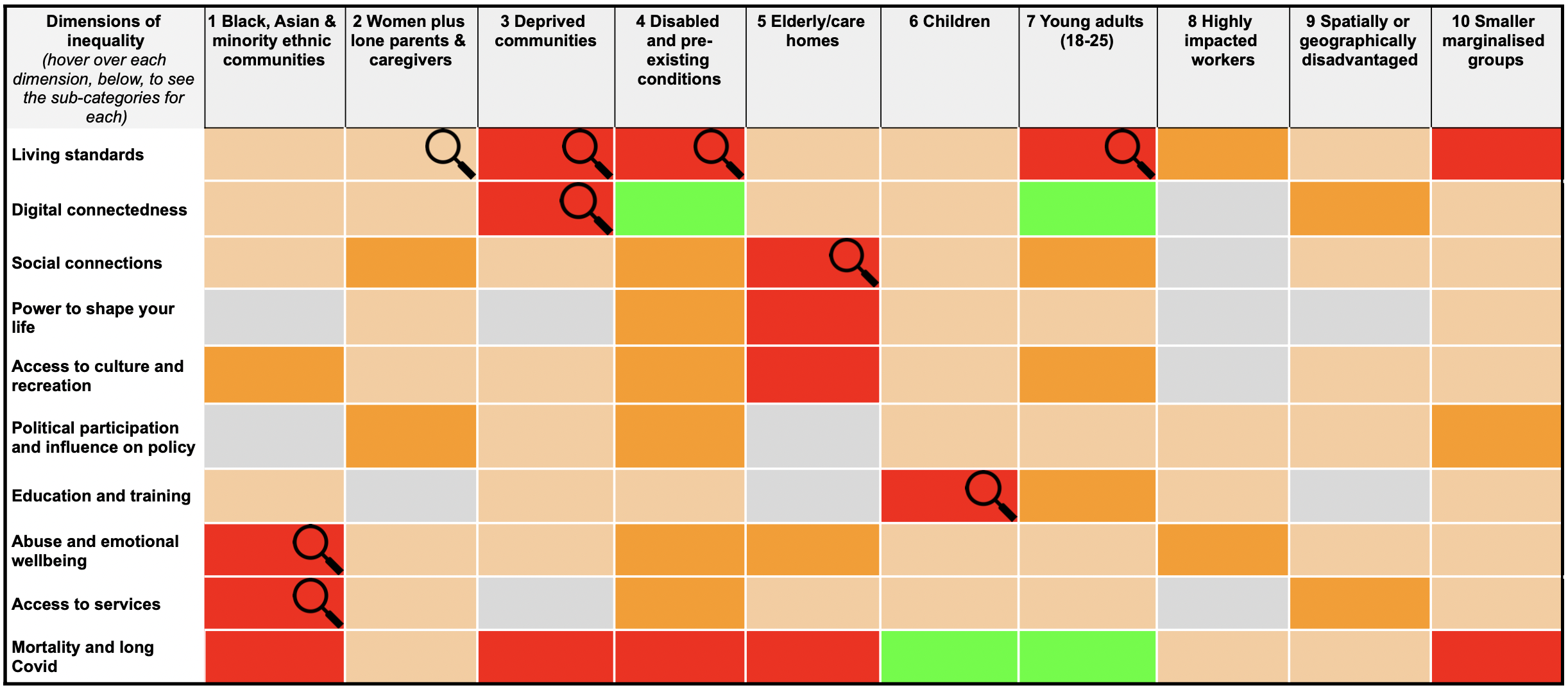

Through our ‘inequalities matrix’, we tried to provide a framework for thinking through the many dimensions of this. Our aim was to better understand how COVID-19 had amplified some existing inequalities – for example, hitting many urban ethnic minority communities particularly hard – while in other respects, its effects had gone against the grain of recent trends in inequality, as with the disproportionate impact on London, or the surprisingly rapid action on street homelessness in the spring of 2020.

The matrix – and the underlying submatrices behind each cell – attempted to indicate where the biggest problems might be (denoted by red segments), and where more research would be most useful (indicated by the magnifying glasses). Our original version is shown below – we are now working through all the many useful comments that it generated during our Action On Inequalities event, and will use these to inform IPPO’s follow-up workstreams over the coming months and more.

Throughout the event, an impressive array of statistics, findings and patterns were shared by the plenary speakers, in our seven parallel working groups, and in the very active Zoom chat to flesh out this analysis – from how incomes of the UK’s poorest households fell furthest in relative terms since March 2020, to the very uneven spatial effects within towns and cities, and the importance of public trust on unequal vaccination take-up.

Our main focus throughout was on practical actions. A key message of the event was that COVID-related social policy responses need to better address ‘intersectionality’ – a concept closely related to older ideas about multiple disadvantage, complex needs and social exclusion. Some aspects of this are very obvious: the disadvantages of being black, female and working class tend to be multiplicative rather than additive, leading to needs that are very different from, say, a 25-year-old female graduate from a Brahmin background. But it’s not so straightforward to understand the complex details, nor to act effectively to address these needs.

Better understanding using patterns, data and experience

These different and often cumulative aspects of inequality and discrimination create challenges both for analysis and for action.

In terms of analysis and diagnosis, it soon becomes clear that although there are broad aggregate patterns, these can hide more specific ones that look quite different. A prominent example is the evidence – which has now been visible for more than 20 years – that educational achievement in the UK doesn’t fit into simple racial frameworks, as white working class boys continue to fall far behind both boys and girls from some ethnic minorities.

Taking seriously the intersection of class, ethnicity and gender means also taking seriously the complexity of the patterns this generates. And as many people pointed out during our event, this generally points to a need for better collection and sharing of data – much of which still doesn’t capture the key categories in enough detail, and therefore misses important inequalities. But it also means taking lived experiences and frontline voices seriously, rather than seeing people merely as ‘categories’. Based on IPPO’s observations of the COVID-19 response, in the UK this is still the exception not the rule.

What to do? How governments handle complex cross-cutting needs

The other big challenge, of course, is what to do with these diagnoses. Governments find it easier to design policies that are suited to aggregate, one-size-fits-all approaches that are easy to push down through their agencies. Much of government is still organised in traditional vertical silos: an education department overseeing schools, a Home Office overseeing policing, and so on. Governments struggle, by contrast, to cope with complex issues and multiple disadvantages of all kinds.

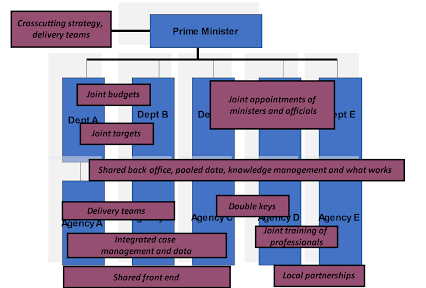

This is not a new insight – it lay behind the public policy writings on ‘wicked problems’ 50 years ago, and has prompted many different types of solution over the years.

The chart below summarises some of the ways governments can deal with crosscutting, intersectional or complex problems: incorporating a range of ministerial responsibilities, task-forces, pooled budgets and ‘double keys’ that can block policies or actions that have not adequately addressed cross-cutting needs. While these approaches, designed to ensure the solutions better fit the shape of the problem, are less common in the UK than in the past, they’re widely used in other countries – and the recent team set up to coordinate work on ‘levelling up’ the UK may be a signal that these approaches are coming back here too.

Chart reproduced from The Art of Public Strategy: Mobilising Power and Knowledge for the Common Good, by Geoff Mulgan

These structures all have equivalents at local level, right down to case managers who can pull together a range of services and supports to meet the real and complex needs of individuals and families – ranging from help with debt and housing to mental health or family support. ‘One-stop shops’ which bring together multiple services (eg. GPs, housing, debt advice) try to do the same, as do many charities which attempt to start with individual needs rather than top-down policy categories.

None of these represent a panacea on their own, however – not least because they create their own challenges and ‘handover’ problems. For example, how should a programme focused on the complex needs of the young unemployed relate to one for single mothers, or another focused on housing needs for families?

In an ideal world, there might be a different tailored policy for every individual family or place, but this isn’t practical. So the best solutions combine some very standardised approaches (such as anti-discrimination or disability rights legislation) with multiple, more targeted interventions which may be time-limited.

A key conclusion if we are to ensure meaningful COVID-19 recovery plans, however, is that some of these devices need to be revived and reinvigorated – with a much sharper focus than the very broad one of levelling up.

Informing COVID recovery plans: the social multiplier

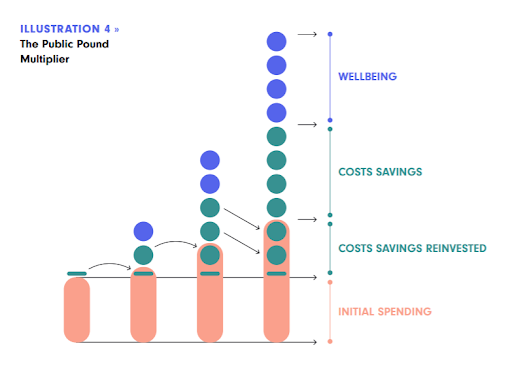

As governments try to pull together recovery plans that address the worst inequalities, they have to prioritise. We’ve been looking at the idea of a ‘social multiplier’ as one way to guide this policy process. The idea of a multiplier is familiar in economics, where it refers to spending that ultimately has a bigger impact because of its knock-on effects.

Over the last few years, work has been done on a ‘public pound multiplier’ – illustrated below – which provides a way of thinking about how some kinds of public spending can achieve savings and better outcomes (these are set out in more detail in this recent report on long-term approaches to public finance).

Chart reproduced from Anticipatory Public Budgeting, by Mulgan et al (a publication by the Global Innovation Council)

A social multiplier is a related idea: identifying policies or actions that will have the most impact across multiple kinds of inequality, ideally in a dynamic way that has growing impact over time. In the development field, reducing child mortality rates is sometimes presented as a form of multiplier, since if you can bring this down it tends to involve actions that also bring many other benefits, both in the short and long term.

As in this example, making problems simpler, rather than more complex, can make sense both analytically and politically (reducing child mortality isn’t of course simple: but focusing on actions that will reduce it can help governments avoid the risk of getting lost in a blizzard of competing priorities).

So a challenge for IPPO over the next few months is to identify other social multiplier options with which UK policymakers at both national and local levels can address the inequalities that have been amplified by COVID-19. For example, is investment in certain types of training the best way to achieve leverage for broader social impacts? Should summer catch-up programmes that are focused on creativity and social skills, rather than purely academic ones, be prioritised? Or is the key need for programmes that are targeted at particular places, and groups within those places, to help them rebuild income?

Money will be tight, of course, so not everything is feasible. The challenge for researchers and policymakers alike is to be sharp about where the biggest impacts can be achieved, moving from diagnosis to prescription and then action.

Sir Geoff Mulgan is Professor of Collective Intelligence, Public Policy and Social Innovation at UCL STEaPP, and IPPO’s Co-investigator

Further reading: recent IPPO blogs on tackling inequalities

COVID-19 has made the case for addressing inequality more compelling than ever. We cannot afford to ignore it – Ian Goldin

For the ‘COVID decade’ ahead, the UK’s intersecting inequalities demand interconnected solutions – Molly Morgan Jones, Joanna Thornborough and Alex Mankoo

The inequality of trust – and why addressing this issue is crucial to a meaningful recovery from COVID-19 – Joanna Chataway and Molly Morgan Jones

Gender

Northern Ireland’s Feminist Recovery Plan: why COVID-19 recovery requires a gender-sensitive approach – Jayne Finlay

Gender inequality and COVID-19: why ‘building back better’ can’t just mean a return to pre-pandemic ‘normal’ – Clara Fischer

How COVID-19 widened the gender research gap as women were left juggling caring and career duties – INGSA case study

Black, Asian & minority ethnic communities

To address ethnic inequalities in COVID-19, we must acknowledge the multifaceted influence of racism – Saffron Karlsen

The value of keeping ethnic ties: why adherence to recommended COVID-19 health behaviours differs among young adults – Angus Holford, Renee Luthra and Adeline Delavande

Other IPPO inequalities blogs

How should we use algorithms to tackle, not widen, social inequalities as part of the COVID-19 recovery? – Zeynep Engin

Danger at work: tracking the multi-layered risks of being a casual worker during COVID-19 – INGSA case study

How to boost UK jobs and skills after the pandemic: four priority areas for action – Geoff Mulgan